How do Wisconsin educators close the academic gap? Start with student mental health.

For K-12 teachers this year, the start of school comes with a series of challenges, closing the academic gap chief among them.

But before teachers can address the academic gap, one of the many fallouts of COVID-19, they'll first need to prioritize the historically high mental health needs of young people.

The majority of Wisconsin high schoolers — nearly 60% — self-reported experiencing depression, anxiety, self-harm or suicidal ideation in the past year. And an unprecedented number of youths are turning up in hospitals for attempting or contemplating suicide.

"We know that students who are mentally healthy experience better outcomes at school," said Libby Strunz, a school mental health consultant for the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction.

Put another way, you can't teach the Pythagorean theorem to someone whose brain is on fire, said Elizabeth Langteau, director of CESA 6 Allies in Mental Health Education, which works with 39 school districts across eight Wisconsin counties. CESA 6, which stands for Cooperative Educational Service Agency, is one of 12 cooperatives in the state and covers Dodge, Fond du Lac, Green Lake, Outagamie, Washington, Waupaca, Waushara and Winnebago counties.

"No one is going to learn when their brains are not in a place where they can access the higher functions of their brain," Langteau said.

Here's what teachers and districts across the state are doing to prioritize mental health in their classrooms:

What's going on with kids?

Research shows that climate change, gun violence and political divisiveness are top concerns for today's youth, according to Linda Hall, director of the Wisconsin Office of Children's Mental Health.

In addition, a reliance on screens means young people potentially have access 24/7 to bullying and schoolyard drama. Looking at a screen all day also makes it difficult to avoid the topics that are causing them the most concern.

Allison Beyerl, a school psychologist and director of learning, counseling and mental health for the Kettle Moraine School District in Waukesha County, said young people tend to have a ton of access to social media — but not a lot of impulse control.

"The stressor I see related to social media is students telling me, 'I did something or I said something online and now I can’t take it back,'" Beyerl said.

Modeling good behavior and establishing trust

When he taught ethnic studies at Vincent High School to juniors and seniors during the pandemic, Demetrius Rice was able to get exhausted students to open up about issues such as why they weren't sleeping by asking open-ended questions, among them "How are you doing?" "What are you going through?" and "What do you need so I can support you?"

Today, Rice teaches sixth-grade social studies at Lincoln Center of the Arts in Milwaukee, and knows the power communication can have on his students.

"Being that one trusted adult can make such a difference, and there's research that backs that," said Andréa Donegan, a school counseling consultant with the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction. "That's something we can all do, no matter what type of staff member we are."

Justin Bestor, the principal of Kettle Moraine High School in Waukesha County, said a trusted adult can be lifesaving for young people. It's especially crucial when a student needs to share concerns about a friend's relationship to self-harm and suicidal thoughts.

"They may feel a little uncomfortable going up to their friend and saying ‘Hey, I saw you posted this story. It’s making me a little nervous about what you said here.’ They’ll go to a trusted adult and say ‘So and so just said this,’" Bestor said.

Recognizing the signs of a mental health challenge

Strunz, from DPI, said more and more school staff are getting trained in youth mental health first aid, which can help everyone from the principal to the custodian identify students experiencing mental health struggles.

In 2023 alone, more than 700 people took part in that training, Strunz said.

Staff members are able to report concerning behaviors to student services and also learn best practices for how to communicate with a student in crisis.

Creating more space for social emotional learning

Social-emotional learning helps children manage their emotions and navigate social interactions.

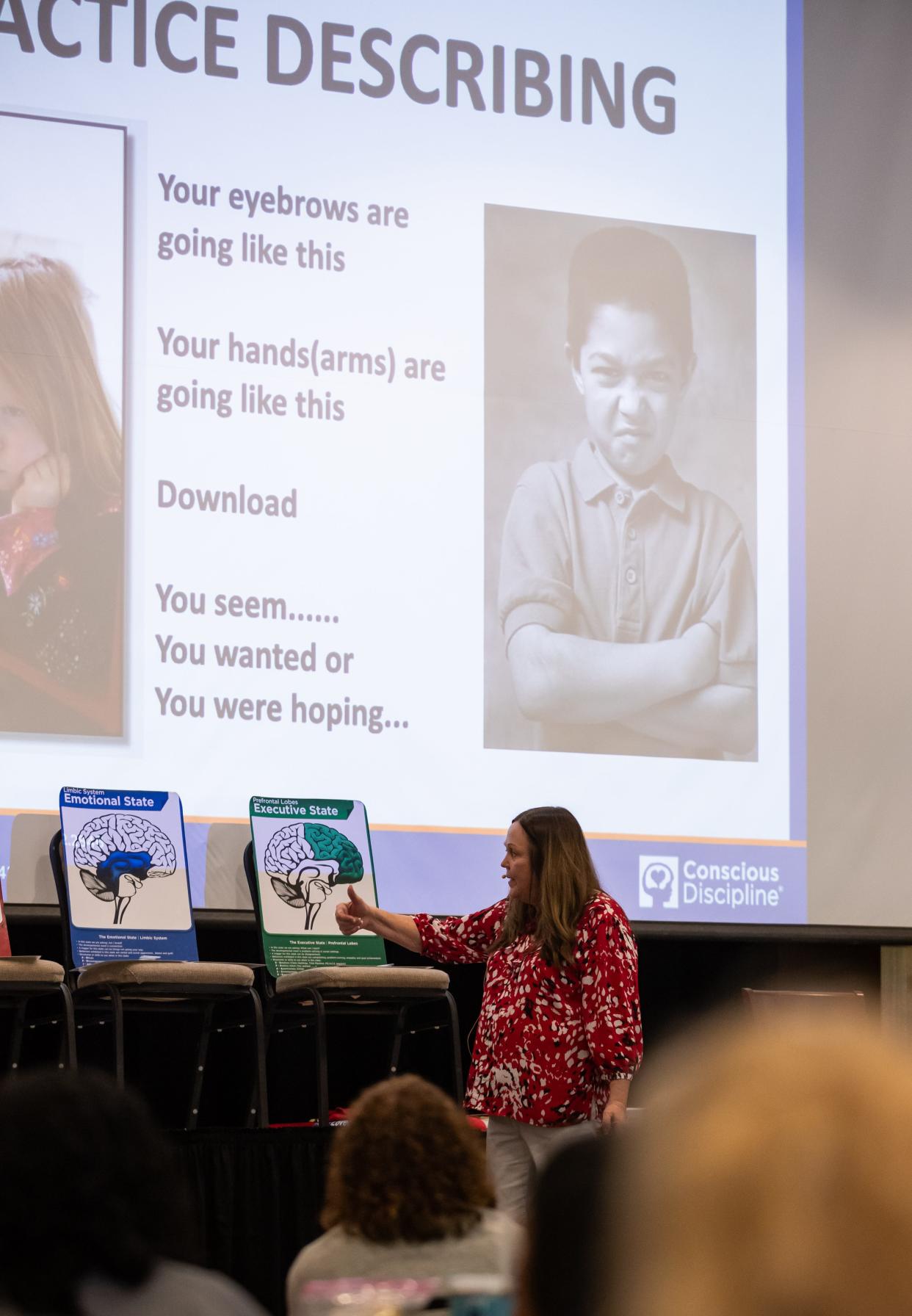

Across Wisconsin, school districts and child care centers are implementing social-emotional programs that give students more ability to control themselves when they're emotionally elevated.

Sometimes it involves a restorative circle, in which teachers of students of all ages arrange their classroom seating in a circle and invite students to open up about what they're struggling with, referred to as Culturally Responsive Minds.

In elementary school, it might look like giving kids the tools they need to form friendships, solve problems, regulate their emotions and help their peers, called Second Step Curriculum.

Danielle Englebert, chief operating officer at the YMCA of the Fox Cities, said she started incorporating Second Step Curriculum with her school-aged children when she realized the kids weren't socializing during the pandemic.

Langteau, from CESA 6, said teachers are changing the layouts of their classrooms. Some classrooms now have a "calm corner," which gives kids the chance to regulate their emotions without having to leave the room.

She also emphasized the need for teachers to have resources in place to establish and build community, and that's on the administrators to provide.

“If teachers are in a place where they’re not feeling safe, not feeling cared for or valued — we’re the same as kids — then we don’t have access to those higher-level functions of our brain and can’t show up as our best selves,” Langteau said.

Journal Sentinel reporters Rory Linnane, Alec Johnson and Amy Schwabe, Post-Crescent reporters Madison Lammert and AnnMarie Hilton, and Green Bay Press-Gazette reporter Danielle DuClos contributed to this report.

Natalie Eilbert covers mental health issues for USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin. She welcomes story tips and feedback. You can reach her at neilbert@gannett.com or view her Twitter profile at @natalie_eilbert. If you or someone you know is dealing with suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or text "Hopeline" to the National Crisis Text Line at 741-741.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Kids in Crisis: Wisconsin educators boost mental health skills