Wisconsin finally has its new election maps. Here is how we got there and what the end result means for voters

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

MADISON – After a year of political and legal brawling, Wisconsin has new congressional and legislative districts.

They’re a lot like the ones that have been in place for the last decade that heavily favor Republicans.

Here’s a look at how the state got here and what it means for Wisconsin’s voters, lawmakers and congressional members for the coming years.

More: See how Wisconsin redistricting changes your voting map

Why were new lines drawn?

Districts must have equal populations to ensure everyone’s vote carries the same weight. Over time, the populations of the districts get out of whack as people move from one district to another.

After the U.S. census each decade, states are required to draw lines to rebalance the populations of their districts. Data from the 2020 census came out last year, kicking off the redistricting process.

Why does it matter how they’re drawn?

Where the lines go can give one political party big advantages.

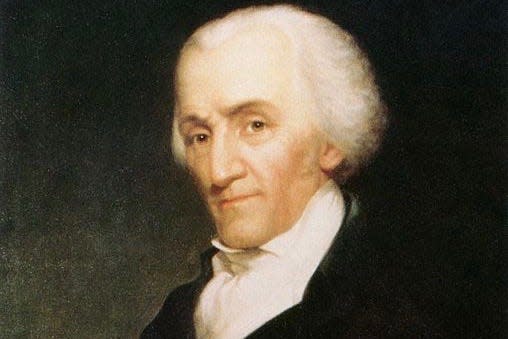

Drawing maps for political gain has been going on since the nation’s early history (after all, the term "gerrymandering" comes from founding father Elbridge Gerry). These days, partisans use computer technology to turn line drawing into a precision science of maximizing political gain.

In 2011, Republicans controlled state government and established districts that greatly favored them.

This time, Republicans in the Legislature had to share power with Democratic Gov. Tony Evers.

More: What is gerrymandering? Redistricting means new winners and losers

What happened in the early stages of redistricting?

From the start, Evers and Republicans made clear they were unlikely to agree on maps.

Evers formed a commission of citizens that he wanted to draw the lines without taking partisanship into account. Republicans said they didn’t trust the panel and set to drawing their own lines.

The maps the commission produced split Democrats, with Evers championing them but some Democratic lawmakers calling them inadequate. Legislators rejected the commission’s plans and Republican lawmakers adopted the ones they drew.

Evers vetoed the Republican maps, leaving the state without a plan.

How did they wind up in court?

Even before anyone produced any maps, litigation over the line-drawing process began in both state and federal courts.

After Evers vetoed the Republican maps, the state Supreme Court agreed to decide on the maps. A panel of three federal judges put litigation it was considering on hold while the state justices took up the issue.

What did the state Supreme Court say about how to draw the maps?

A 4-3 majority issued a crucial decision in November that said it would adopt maps with as few changes as possible to the ones drawn in 2011. That was a victory for Republicans because the 2011 maps so heavily favor their party.

The court then told all sides to submit proposals based on the November ruling.

Which congressional maps were chosen?

In March, a different 4-3 majority picked congressional maps drawn by Evers because it found they made the fewest changes of all those submitted to it.

Those maps — which will be in effect this fall — will give Republicans a lock on four of the state’s congressional districts and an advantage in two others. Democrats will have a lock on the state’s remaining two districts.

Republicans currently hold five seats and Democrats hold three.

Under the new plan, Republican Rep. Bryan Steil’s district in southeastern Wisconsin will become much more competitive. It will still lean Republican but by a much smaller margin.

Which maps did the state Supreme Court choose (the first time)?

In its March decision, the state justices also selected Evers’ plans for state Senate and Assembly districts. Under those plans, Republicans would be on track to maintain their majorities in the Legislature but likely by smaller margins.

What did the U.S. Supreme Court say?

Republicans appealed the state court’s decision to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The nation’s high court left in place Evers’ congressional maps but threw out his plans for the Legislature. The unsigned opinion found that the state court had not properly explained its rationale for adopting maps that increased the number of Assembly districts with Black majorities from six to seven in Milwaukee.

The U.S. Supreme Court returned the legislative maps to the state justices, telling them to select new maps or justify their reasons for picking Evers’ maps.

Which maps did the state Supreme Court choose (the second time)?

On April 15, a 4-3 majority of the state Supreme Court chose Republican lawmakers’ maps. The majority wrote that the state had to adopt maps that didn’t take the race of voters into account.

Who benefits from the maps?

The maps will likely bolster Republicans’ control of the Legislature.

They will have the advantage in 63 of the Assembly’s 99 districts and 23 of the Senate’s 33 districts. Those are slightly bigger numbers than the ones they hold now — 61 in the Assembly and 21 in the Senate.

How did the state justices break on these decisions?

Brian Hagedorn proved to be the crucial justice throughout the redistricting fight. Hagedorn was elected in 2019 with the help of Republicans but has frustrated the party’s stalwarts in some high-profile decisions during his short tenure on the court.

Hagedorn joined with the court’s conservatives in the November decision that said the court would adopt as few changes to the 2011 maps as possible.

In March, he joined the court’s liberals in the decision that picked Evers’ maps.

After the U.S. Supreme Court threw out the March decision, Hagedorn joined with the conservatives to pick the Republican lawmakers’ maps for the Legislature.

What’s next?

The maps for the Legislature and Congress are all but certain to be used for this fall’s election, but court challenges could continue over what maps to use in 2024 and beyond. Democrats and others may seek to revive federal lawsuits that were filed early on or initiate new litigation.

Legal fights over the 2011 maps lasted nearly a decade.

About this feature

This is a weekly feature for online and Sunday print readers delving into an issue in the news and explaining the actions of policymakers. Email suggestions for future topics to jsmetro@jrn.com.

Contact Patrick Marley at patrick.marley@jrn.com. Follow him on Twitter at @patrickdmarley.

Our subscribers make this reporting possible. Please consider supporting local journalism by subscribing to the Journal Sentinel at jsonline.com/deal.

DOWNLOAD THE APP: Get the latest news, sports and more

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Here's what Wisconsin's new election maps mean for voters