These Wisconsin high school students, inspired by their First Nations education, are rallying against Native American mascots

PRESCOTT - “Change your logo!”

That's one chant that can be heard by Prescott High School students attending away sports games at rival schools that use Indigenous-based mascots in western Wisconsin.

“Coming from a small, predominantly white community, I don’t think many schools around here care about this issue,” said Rian Engeldinger, a senior on the Prescott student council.

But she and others are working to change that.

Many students from her school in the past have worn shirts depicting a protest of the use of such mascots and some students and community members from the rival school were even motivated to order their own shirts from Prescott campaigns.

Students at Prescott High School in Prescott, Wisconsin, about 30 minutes from Minneapolis, know their First Nations education curriculum is exceptional and some aim to take what they’ve learned to help educate people in surrounding school districts.

The governments of every Indigenous nation in Wisconsin oppose the use of race-based mascots and logos, arguing they cause harmful stereotypes, as state officials are reminded of every year during the State of the Tribes’ Address.

The Prescott Cardinals play against the Baldwin-Woodville Blackhawks and the Osceola Chieftains, which are two of more than two dozen school districts in Wisconsin that still use Indigenous-based mascots or logos.

“The tribes that are right down the road don’t approve (of these mascots),” said Zach Simones, who helped lead the first Prescott student protest against Native American-based mascots in 2009.

Prescott teachers work with some of the top tribal education leaders in the state, including with the First Nations program at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay.

Simones had become impassioned about the mascot issue after learning how offensive it was to Native peoples in his First Nations education at Prescott and after meeting with Barb Munson, who leads the Wisconsin Indian Education Association’s mascot task force.

She has been working since the 1990s to educate Wisconsin school officials about why they shouldn’t use these mascots and has had some success.

Sign up for the First Nations Wisconsin newsletter Click here to get all of our Indigenous news coverage right in your inbox

With some national teams, such as the Washington NFL team and the Cleveland major league baseball team recently dropping their mascots because of their offensive nature, Munson and supporters like Simones had hoped Wisconsin school districts would finally get the message.

Officials with some school districts are considering the issue, but some cite the costs to change their logos.

Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers weighed in on the issue last year by proposing a small portion of tribal gaming revenue be used to give to school districts looking to change their Indigenous-based logos, such as for repainting gym floors.

The money ultimately did not make it into the final budget.

Back in 2009, Simones and other Prescott students traveled to Madison and successfully petitioned state lawmakers to pass legislation to ban race-based mascots.

Under the law, anyone could file a complaint with the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, which would determine if a mascot is race-based.

Former Gov. Scott Walker and other Republican members of the Legislature then amended the law to state the plaintiff must obtain a certain number of signatures from the community to challenge if a mascot is race-based.

Simones said that defeated the purpose of the original law, which was to help protect a petitioner from being ostracized by the community for wanting to change the mascot.

Prescott students say many would change their minds about mascots if they would take the time to learn more about Indigenous communities or even visit one.

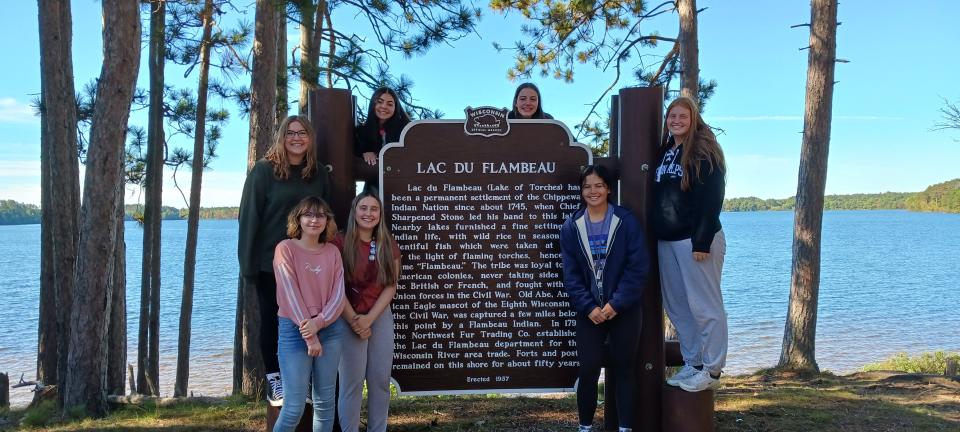

A group of Prescott students visit the Lac du Flambeau Ojibwe Reservation in Wisconsin every year.

Not only do they hear from tribal elders and others on the reservation about how race-based mascots are offensive, but they learn about other issues, such as tribal sovereignty and the infamous “Walleye Wars” in northern Wisconsin.

This was a series of sometimes violent and racial incidents in Wisconsin in the 1980s and 1990s when Ojibwe citizens started practicing their treaty rights with the federal government to spearfish in ceded territory, or off-reservation land that had once belonged to the Ojibwe.

Many non-Native anglers and their supporters had confronted Ojibwe spearfishers on and off Wisconsin waters.

RELATED: Advocates continue efforts for Wisconsin school districts to drop use of Native American mascots

State legislators later created Act 31, which mandates First Nations education in Wisconsin, in part to help educate residents about the existence of tribal and federal treaties and the rights for Ojibwe to spearfish in Wisconsin.

Prescott student Tessa Schmidt, who recently visited Lac du Flambeau, said she realizes not many students in Wisconsin know about the Walleye Wars.

“It’s such a big part of our history, and yet no one knows about it,” she said.

State educators acknowledge many school districts in Wisconsin are not living up to Act 31.

Schmidt believes so much can be learned if residents just talk to First Nations peoples.

“They’re so kind and we were welcomed by the people,” she said about her visit to the reservation. “They’re so willing to talk about their struggles, but they’re still overlooked. Every person wants to be understood and appreciated. They want to tell their stories, but not everyone wants to listen.”

Prescott student Rebecca Heinze said the visit to Lac du Flambeau helped her understand the Walleye Wars on a more personal level.

“My dad always says that listening is easy, but understanding is harder,” she said. “You can learn from a textbook, but seeing the emotion in their faces recounting stories (of the Walleye Wars) helped me understand how important it was. It’s still a very open wound for them.”

Frank Vaisvilas is a Report for America corps member who covers Native American issues in Wisconsin based at the Green Bay Press-Gazette. Contact him at fvaisvilas@gannett.com or 815-260-2262. Follow him on Twitter at @vaisvilas_frank. You can directly support his work with a tax-deductible donation online at GreenBayPressGazette.com/RFA or by check made out to The GroundTruth Project with subject line Report for America Green Bay Press Gazette Campaign. Address: The GroundTruth Project, Lockbox Services, 9450 SW Gemini Drive, PMB 46837, Beaverton, Oregon 97008-7105.

This article originally appeared on Green Bay Press-Gazette: Wisconsin Native American school mascots spur student protests