Wisconsin preschoolers are 5 times more likely to be expelled than K-12 students, but why?

This story was produced as part of the NEW (Northeast Wisconsin) News Lab, a consortium of six news outlets covering northeastern Wisconsin.

When Rachael Van Domelen answers calls from her son’s child care center, she braces herself for uncomfortable conversations: apologies to another child’s parents, a sit-down with her 4-year-old or both.

One time, her son split open a teacher’s lip with a block. He hits other children or calls them names when he disagrees. His father, Mason Beaudry, called these episodes “explosive” and unpredictable.

“He’s so smart, it hurts. It makes things harder to navigate,” Van Domelen said. “If he's upset and wants to upset someone else around him, it does not take him very long to figure out how to do that.”

This intelligence is also evident in the 4-year-old’s endless curiosity. He loves nature; when he goes on walks, he turns over every rock to look at the bugs beneath. He even has a pet python named Kemosabe, an ode to the “Lone Ranger” character.

“He has a huge personality, and he absolutely will let you see every side of it,” she said.

Both parents say they're lucky to have their son at Bridges Child Enrichment Center, which they feel strengthens his best qualities while focusing on specialized support.

But not all families are so fortunate. A 2005 nationwide study found children in state-funded prekindergarten programs — including school settings, child care programs and more — were three times likelier to be expelled than students in K-12 schools. In Wisconsin, that rate was more than five times higher.

There's no evidence the trend has improved, said Walter Gilliam, the researcher behind the 2005 study.

And behavioral issues, the No. 1 cause of early childhood expulsions in Wisconsin, are skyrocketing. According to a 2021 survey, more than half of Wisconsin early care and education professionals reported an increase in challenging behaviors, such as aggression and acting out. That's on par with national findings.

Aggressive behaviors drive many early childhood expulsions

Erika Brigham had less than a week to make alternative plans for her 4-year-old son when she learned his child care program in Rhinelander was expelling him.

Outside his child care program, he didn't show the aggressive behaviors the program expelled him for. At home, he spent much of his time playing with bubbles and experimenting with makeup. He behaved well at 4K, but when he was in child care, a different setting, things took a dramatic turn.

When the expulsion notice came, Brigham felt like she was experiencing déjà vu.

Two years ago, when her older son was 6, his summer camp expelled him for similar aggressive behaviors.

Her older son is curious, always taking things apart and putting them back together. He taught himself to read in a two-week period. He also has autism along with myriad behavioral diagnoses, which make it hard for him to regulate his emotional responses.

Brigham tried to set him up for success: She sat down with the summer camp director for two hours, outlining step-by-step how to best support her child.

But the call came from summer camp anyway. And years later, she received similar calls about her younger son.

“It's extremely disappointing," Brigham said. "We're used to getting those phone calls, but you just hope that everything will be fine."

Susan Steinhofer, an outreach navigator with the community organization First 5 Fox Valley, has spent decades working in the field, and has seen countless children act similarly to Brigham’s boys.

Steinhofer said there have always been preschool expulsions, but today’s landscape has some marked differences. Today’s children experience a unique set of stressors, much of which stem from COVID-19. The pandemic jolted parents' mental health and slowed children's development. Child care is also hard to find and afford as the field contends with a shortage of experienced teachers.

“This is an issue with a lot of complicating factors,” Steinhofer said.

Related: The new Wisconsin family? 1.7 kids, no picket fence and child care costs more than college

It's tempting to associate a child's behavior with their character, but there's often more to the story

Jasmine Waldner operates Cedar Glade Family Learning Center out of her McFarland home. When a family came to her desperate to find care for their 2½-year-old son who had been expelled from a different program, Waldner didn’t think much of it. Her small program often allowed her to better care for kids with all kinds of behaviors, she said.

Waldner soon realized she was out of her depth.

In the six months under Waldner’s care, the child hit and bit, played with his feces and, once, dumped his urine all over the table, chairs and carpet.

Waldner was determined to work through the child’s behavioral challenges. She helped the parents sign on to the state Birth to 3 program, which serves as early intervention for children younger than 3 with developmental delays and disabilities. Soon, he had a team of specialists who worked with him in a separate room.

When the child rejoined the other children in the main play space, he immediately knocked a child to the ground.

Even though it might be hard to picture small children flipping furniture, tipping shelves and hurting adults, Bridges Executive Director Nicole Desten said these are fairly common behaviors for children who become severely dysregulated. That’s because they haven’t developed the language skills necessary to identify, explain and cope with difficult emotions.

Adding to the problem, Desten said, parents may hesitate to disclose challenging behaviors at enrollment, fearing their child will be denied care or teachers will expect the child to misbehave. But withholding crucial information can delay help.

Van Domelen and Beaudry’s 4-year-old started exhibiting aggressive behaviors shortly after he turned 2, when he went through many transitions in a short time. He moved into a new classroom at Bridges, and his father was in prison for a year.

“Very normal things really agitated him because of (Beaudry's) lack of physical presence,” Van Domelen said. “When (Beaudry) was present again … it was a huge agitation. What can you really expect a little person like that to understand?”

Nationwide, the pandemic was its own transition. Stay-at-home orders often denied children opportunities to socialize with peers and other adults. Many parents, forced to work remotely, performed their job duties while simultaneously looking after their kids, Desten said.

Sometimes, Desten said, parents handed their children screens so they could cram in a few hours of work. Many children used screens as a coping mechanism when upset, which didn’t translate once they were in classrooms.

“There has always been a gap between school expectations and home (expectations) … but that gap has widened,” Desten said. “Now you have these children coming to school and child care that have had very little structure or few expectations. They don’t know how to communicate their needs and emotions or follow an established routine.”

In Waldner’s case, the child continued to communicate his challenges through aggression despite various intervention attempts. At pickups and drop offs, other parents would tell Waldner they were worried for their own children’s safety.

Ultimately, Waldner did what she hoped she’d never have to do: She gave the parents two weeks to find alternative child care for their son.

“Some of it still makes my head go on edge because it was scary. I had to let him go, even though we worked so hard to get support in place," Waldner said. "How do you help that child, when you physically cannot help him in the space that you have?”

Boys, Black preschoolers and those with disabilities are expelled at higher rates than their peers

Data show children of certain genders, races and abilities are more vulnerable to early childhood expulsions.

The 2005 study found Black preschoolers were twice as likely to be expelled than white preschoolers, and boys were more than four times as likely to be expelled than girls. When putting these facts together, the statistics looked particularly grim for Black boys.

Years later, these gender and racial disparities still exist.

A 2016 study spearheaded by Gilliam used eye-tracking technology to examine the role implicit bias plays in early childhood expulsions. When watching a group of students playing, teachers spent the most time watching the Black boy, waiting for bad behavior that never came.

This could be because teachers expect boys, specifically Black boys, to misbehave, indicating bias, Gilliam said.

Black boys aren’t the only ones bearing a disproportionate brunt of expulsions. According to a Civil Rights Data Collection Report, which tracked 2017-18 data, preschool children with disabilities made up 60% of all expulsions, despite an enrollment of nearly 23%.

Brigham knows of eight families with children who were expelled from the same child care center her sons attended. All had children with special needs, she said.

Children with disabilities see larger developmental gains when they are not separated from other children based on ability, according to Gilliam, who's now the executive director of Buffett Early Childhood Institute at the University of Nebraska, and Rosemarie Allen, president and CEO of the Institute for Racial Equity and Excellence.

Brooke Skidmore, co-owner of The Growing Tree child care center in New Glarus, said when children of different abilities are in class together, the children who do not have disabilities learn empathy and how to advocate for their peers — skills they use throughout their lives.

Earlier this year, a former student of Skidmore’s, who has Down syndrome, celebrated her 17th birthday. The party guests were her classmates from when she attended The Growing Tree and represented a range of abilities.

As pointed out in Gilliam and Allen’s writing, early childhood programs often refer families to early intervention services, mental health resources and more. In this way, those who benefit from early childhood education the most are often kept out of it — and research shows doing so can ultimately set them up for failure.

Related: One in 5 could have dyslexia, but Wisconsin students, parents feel school support falls short

With no checks and balances in place for child care expulsions, there's little protection

While Gilliam’s 2005 study showed the overall expulsion rate in preschool settings was three times that of K-12, the rate for child care centers specifically, such as privately owned and operated day cares, was 13 times that rate.

In Wisconsin, part of this phenomena can be explained by how the child care system is set up.

Under Wisconsin law, a child must attend school at a public, private or approved home school environment beginning at age 6. Because expelling a child in most K-12 settings is at odds with this law, it requires a stringent process that includes a hearing and, potentially, an appeals process.

It’s an entirely different ball game with child care programs, except potentially for students with disabilities. State licensing requirements don't include any expulsions-related procedures for child care programs to follow — although Wisconsin’s Early Childhood Suspension and Expulsion Reduction Project is looking into this area, said Department of Children and Families Communications Director Gina Paige.

Gilliam said early childhood education professionals experience a dearth of resources compared to K-12 schools. When early educators have access to resources, many don't know they exist, research shows.

More: Your child needs mental health counseling. Get ready to wait weeks, with no guarantee of a good fit.

Child care industry staffing shortages impact the whole classroom

Child care professionals often earn meager wages without job-sponsored benefits. This, plus the demanding nature of the work, results in turnover rates of more than 40%.

This can make it difficult for some child care businesses to justify the additional costs of providing advanced social-emotional training to their staff, said Karyn VanRyzin, director of the Kimberly-based Community Child Care Center.

In the end, it's the children who suffer.

“The basis for health and mental health is forming trust, and trust is what is formed in those early years,” VanRyzin said. “If a child has a revolving door of caregivers, or doesn't have quality caregivers — meaning their needs aren't met on a consistent basis — then their learning is negatively impacted.”

Per state licensing requirements, the number of teachers a child care center has directly affects how many children it can serve. Given the field’s staffing shortage, if an overwhelmed teacher leaves, they're difficult to replace. When they can’t be replaced, an entire classroom may be forced to close.

It’s also understandable, VanRyzin said, when families choose to disenroll their child from a program if a peer is causing safety concerns.

More: Staffing crisis forcing some Fox Cities child cares to 4-day week, fewer children

More: Bellevue child care center to close after 20 years in business

Child care waitlists can reach into the 100s. From a financial standpoint, expelling children doesn't hurt a child care program’s bottom line — that space can easily be filled. Long waitlists make it tempting for child care programs to simply never enroll children with exceptional needs.

“When you have really long waitlists and you can’t find staff, then you might be more apt to handpick the kids that you want,” Desten said. “When I have a waitlist of over 100, I could pick the 100 ‘easy’ kids for my center, since I don’t need the 20 ‘difficult’ children to remain full. But then, where do those 20 children go? How do their parents work?”

Children expelled from early education are likely to struggle academically and beyond

Most people can quickly conjure the name of the “bad” kid from their early school years. Once the label is applied, it’s a hard reputation to shake. That association can shift how children view themselves, said Briana Kurlinkus, early childcare trainer at 4C, Community Coordinated Child Care Inc, in south central Wisconsin.

Expelled children see themselves as less capable of succeeding in school, Kurlinkus said, and will more than likely live up to their reputation.

Brigham’s older child agonizes over his mistakes. As an 8-year-old, her son already exhibits suicidal ideation, even though he doesn’t fully comprehend the gravity of his statements, she said.

“He says things like, ‘I wish I was never born,’ or ‘Why did you have me? I never asked to be here,’” Brigham said.

Children with behavioral challenges are often expelled multiple times from different programs, thrusting them into a cycle that never addresses their needs and further solidifies harmful labels.

Drawing from multiple studies, Gilliam said children who were suspended or expelled in elementary school were more likely to have negative attitudes about school and future academic failure. They are 10 times more likely to drop out of high school, and eight times more likely to be involved with the juvenile and adult justice systems. He said he expects this would also apply — or even be more significant — for children expelled from preschool.

Years after Gilliam first published his research on preschool expulsions, he made a startling connection: Data from the Vera Institute of Justice showed the incarceration rate mirrored the rate of preschool expulsions from 15 years earlier.

Gilliam also found the gender and race disparities in his preschool expulsion research nearly matched the demographics of adult incarceration. Those children he initially researched in 2005 would be between 17 and 20 by 2019.

“That doesn't prove that there's a preschool-to-prison pipeline. But if there is, it's amazing how consistent the diameter of the pipe is,” Gilliam said.

Families are also impacted by early childhood expulsions.

“When a child is expelled from a preschool program, in many cases, it also means that their parent is now expelled from employability,” Gilliam said. “As a result, the parent can’t go to work, (and) that’s going to increase economic insecurity on the family, food insecurity on the family and parental stress.”

On a more extreme level, parental stress, Gilliam said, can be a predictor of child abuse, “and then they don’t show up in educational statistics. They show up in child protection services statistics.”

'Mommy, do you want to take some deep breaths with me?': Early intervention empowers children, families

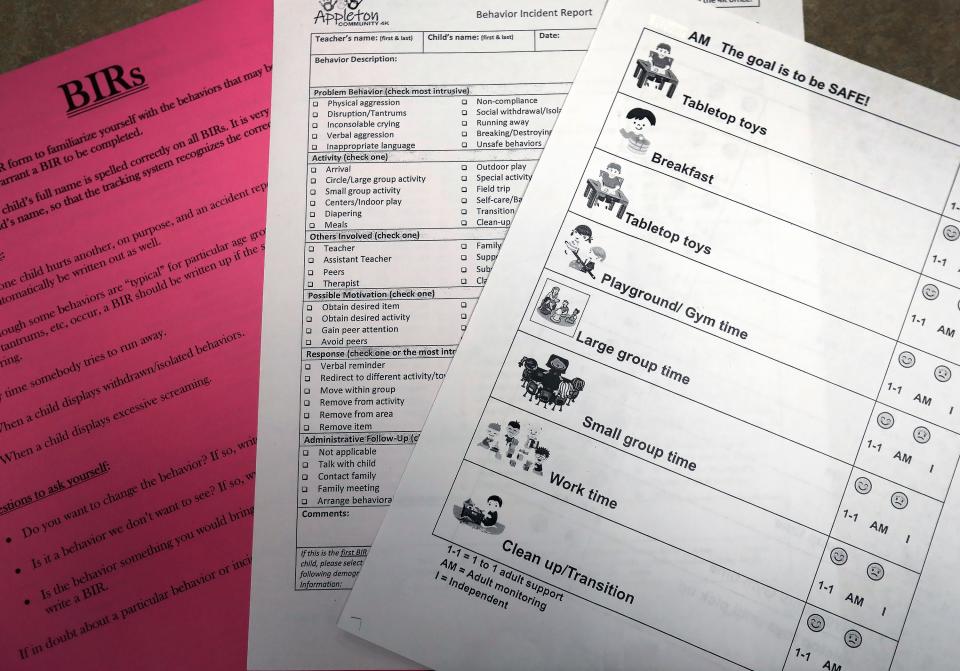

It’s been years since Van Domelen and Beaudry’s son started at Bridges. He now receives a daily report card, but instead of academic subjects like reading and math, it's broken down hour-by-hour. Little faces replace letter grades; green denotes positive behavior, red signals a setback.

When Van Domelen’s son darts into her arms from across the classroom, beaming with pride and waving his report card around, she knows he scored all green. Though he still struggles, these green days are increasingly frequent.

At Bridges, the 4-year-old can receive on-site therapy sessions during the school day, and, in the classroom, a behavioral specialist works closely with him and other children who need extra adult attention.

At home when he’s feeling dysregulated, the 4-year-old chills in his "yoga corner" in the living room. Sometimes, when Van Domelen is having a rough day, he scoots next to her on the couch and asks, “Mommy, do you want to take some deep breaths with me?”

This reminds her of the skills they worked so hard to teach him.

“All of the energy that you put into it — which is going to be a lot — is going to come full circle, and you’re going to know you’re doing something right,” she said.

Related: How 'Mindfulness Wednesdays' at Tank Elementary School led to a 30% decrease in discipline referrals

This story is part of the NEW (Northeast Wisconsin) News Lab's fourth series, "Families Matter," covering issues important to families in the region. The lab is a local news collaboration in northeast Wisconsin made up of six news organizations: the Green Bay Press-Gazette, Appleton Post-Crescent, FoxValley365, The Press Times, Wisconsin Public Radio and Wisconsin Watch. The University of Wisconsin-Green Bay’s Journalism Department is an educational partner. Microsoft is providing financial support to the Greater Green Bay Community Foundation and Community Foundation for the Fox Valley Region to fund the initiative. The mission of the lab is to “collaborate to identify and fill information gaps to help residents explore ways to improve their communities and lives — and strengthen democracy.”

READ THE SERIES:

Week 17: Breaking the cycle: Local building projects, state aid helping some reclaim 'the American dream'

Week 15: Breaking the cycle: Here's why pathways to higher education are vital for first-generation students

Week 14: With 'Silver Tsunami' on the horizon, condition complaints at senior living facilities surge

Week 13: Wisconsin foster children often need mental health care to thrive. Why is it hard to help them?

Week 12: Breaking the cycle: Intergenerational trauma has real impacts on lives, connections of Wisconsinites

Week 11: Rising cost of living in northeast Wisconsin has many working families treading water

Week 8: One in 5 could have dyslexia, but Wisconsin students, parents feel school support falls short

Week 7: Breaking the cycle: Addressing generational patterns key to improving quality of life

Week 6: It takes a village: How collaboration helped a small northern Wisconsin city add crucial child care

Week 5: Wisconsin families matter. Here's how 6 newsrooms, 2 community foundations and Microsoft aim to help

Week 4: Many kids missed dental care during the pandemic. Luckily, these dentists visit schools for free

Week 1: The new Wisconsin family? 1.7 kids, no picket fence and child care costs more than college

Natalie Eilbert covers mental health issues for USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin. She welcomes story tips and feedback. You can reach her at neilbert@gannett.com or view her Twitter profile at @natalie_eilbert. If you or someone you know is dealing with suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or text "Hopeline" to the National Crisis Text Line at 741-741.

Madison Lammert covers child care and early education across Wisconsin as a Report for America corps member based at The Appleton Post-Crescent. To contact her, email mlammert@gannett.com or call 920-993-7108. Please consider supporting journalism that informs our democracy with a tax-deductible gift to Report for America.

This article originally appeared on Green Bay Press-Gazette: In Wisconsin, preschool expulsions are more common than you think