These Wisconsin programs are cracking the code on lowering preschool suspensions, expulsions

This story was produced as part of the NEW (Northeast Wisconsin) News Lab, a consortium of six news outlets covering northeastern Wisconsin.

Stephanie Springer can’t help but tear up when she tells the story of the 6-year-old girl who came under her care last year.

Although the girl is not yet in first grade, she’s already experienced trauma from varying origin points. She expresses her painful past in big, aggressive behaviors toward children and adults.

A child and family advocate at Encompass Early Education and Care, Inc., Springer’s job is to add extra layers of support for children, educators and families. In the case of the 6-year-old girl, this meant working with the child one-on-one, her mother to set up counseling services and the school district to arrange an Individualized Education Program (IEP).

“She's really getting support from every single adult that she's interacting with within the day,” Springer said.

While the cases Encompass advocates see vary in intensity, the notion of having all hands on deck — families, educators and the child — remains a common theme.

Years before becoming an Encompass child and family advocate, Ashley Eslinger worked with a little girl who would have outbursts daily at 10 a.m. All it took to prevent future incidents was ensuring the family made time for breakfast. For other children, the remedy may be noise-canceling headphones when the cacophony of other young children gets too overwhelming.

Encompass's Child and Classroom Advocate Program is just one example of the many potential solutions cropping up across the state working to reduce the large number of early childhood suspensions and expulsions.

Children in Wisconsin state-funded prekindergarten programs — which include those within child care programs, schools and other settings — are five times likelier to be expelled than students in the state’s K-12 schools, a novel 2005 study found.

And nearly two decades later, the tides don’t appear to be changing. In a 2021 survey, most Wisconsin early education professionals reported an increase in behavioral challenges.

Read part one: Wisconsin preschoolers are 5 times more likely to be expelled than K-12 students, but why?

Encompass program more than triples its retention rate

Before Encompass established the Child and Classroom Advocate Program in 2018, its expulsion rate was on the rise for years. Families didn’t always have the resources to set their children up for success — whether due to financial stress or limited access to early intervention programs. This affected classroom dynamics, Encompass executive director Missy Schmeling said.

Children acted aggressively at younger ages — often just 2 or 3 years old — leaving teachers at a loss. Encompass leadership knew it had to improve retention since children have better long-term outcomes when they can stay in child care settings.

After securing grant funding, the Child and Classroom Advocate Program began. It uses a three-pronged approach that includes the family, educators and child.

“For so many years, these positions were siloed. We realized we were missing the mark — advocates who worked with families weren’t working with children in the classrooms,” said Kristin Biely, early education support director at Encompass.

The first big step at Encompass, Biely said, is for advocates to gain trust with the child and classroom teachers. Only then can advocates work on the skills necessary to help the child cope and regulate, both when they’re calm and elevated.

Advocates observe children who exhibit challenging behaviors in their classrooms, looking for insights.

“We try to identify what some of the triggers are — some of the little tells that the kids can have,” Springer said. “When you can start to see what’s coming … and catch it before it escalates, it really helps. And from there, it takes practice, practice, practice.”

After sharing their discoveries with the child’s teacher, the advocate might recommend the child snuggle in a cozy corner for some alone time or play with a fidget toy.

There’s evidence that this program is working. Over the last five years, Schmeling said Encompass’ retention rate has more than tripled for children with challenging behaviors.

More: Encompass to bring a new child care center to Oconto Falls, addresses child care desert

Bridges enlists therapists, creates specific positions for more support

Appleton’s Bridges Child Enrichment Center prides itself on living up to its tagline, “A learning environment for all children.” Few things, Bridges’ staff believes, rupture a child’s learning more than suspensions and expulsions.

During Nicole Destin's 18-year tenure as Bridges' executive director, the center hasn't asked a child to leave for behavior. To buck nationwide early education expulsion statistics, Bridges has multiple supports in place.

Nancy Hidde started as Bridges’ behavior specialist almost three years ago to support teachers and the rest of the Bridges team as they navigated challenging behaviors, similar to Encompass’ advocates.

The behavior specialist's job mirrors a detective’s — they examine patterns and triggers, with a focus on data.

“Say that Joe is having a tough time every Wednesday. To figure out what’s going on Wednesday, we can ask what’s going on Tuesday night. We might talk to the parents and find out Joe switches from Mom to Dad Tuesday,” Hidde said. “Then we can implement some strategies to make them more successful. You can hit it hard when you find out what’s going on.”

The behavior specialist may then propose strategies for teachers in the classroom, provide guidance to families and recommend additional resources. Sometimes, the behavior specialist may suggest a more formal intervention plan, even an IEP or, for younger children, an individualized family service plan (IFSP).

When a child comes in with an IEP or IFSP, Desten said the behavior specialist helps ensure the classroom understands the plan and consistently supports the child to meet their goals.

Bridges also has a Family and Program Support teacher. Desten explained this position has a variety of duties, including ensuring new students or those transitioning to a new classroom get a developmental screening. Then, they look for any red flags that may warrant intervention.

Additionally, Bridges partners with mental health consultants from Catalpa Health, an Appleton-based organization. These consultants, who have on-site offices, observe the classrooms once or twice a year, but for the most part, they’re sitting down for deeper conversations with the teachers and parents to discuss what’s going well, what’s not and if any specific children need support.

The Catalpa consultants also offer on-site child and family therapy, which is covered through the family’s insurance. Catalpa also has a financial assistance program should costs be too prohibitive for families.

More: Pandemic, aftermath add more stress to Wisconsin early childhood teachers' mental health

Mental health consultation programs prevent early childhood expulsions. Now, Wisconsin has one, too.

Desten said Bridges and Catalpa Health designed their partnerships with the principles of Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation (IECMHC) in mind — a program lauded for reducing and preventing early education expulsions.

Under an IECMHC program, mental health professionals work directly with the adults in a child’s life to equip them with better tools to support the children in their care and address behavioral challenges.

A growing body of research shows it works.

Walter Gilliam, the researcher behind the original 2005 preschool expulsions study, found prekindergarten teachers who had ongoing relationships with early childhood mental health consultants in their classrooms were roughly half as likely to report expelling a preschooler than those without this service.

Evaluations of statewide IECMHC programs in both Connecticut and Ohio show they reduce challenging behaviors.

Consultation — provided by mental health clinicians with specialized training in infant and early childhood mental health — helps adults increase their self-awareness and build self-regulating skills, said Lana Shklyar Nenide, the executive director at Wisconsin Alliance for Infant Mental Health (WI-AIMH).

“We will not have enough mental health clinicians for every child who might need this level of support — it’s just not possible,” said Nenide. “But, when you support teachers, instead of helping one child at a time, you really are helping groups of children. IECMHC programs have been very effective in that way.”

Picking up on these programs’ success, Wisconsin devoted federal pandemic relief funding to implement a statewide IECMHC program called "Healthy Minds Healthy Children." Wisconsin’s Department of Children and Families and WI-AIMH are teaming up on the project.

A launch of Healthy Minds Healthy Children is underway in southeast Wisconsin, according to Priya Bhatia, administrator for DCF’s Division of Early Care and Education. She said the program will expand to northern and southern regions next year.

Consultation under Healthy Minds Healthy Children can be implemented on a micro-level, focusing on a specific child’s behaviors, or a macro-level, helping a classroom or even entire program support the needs of all children.

Bhatia said clients usually receive 10 to 12 hours of consultation services each month for one to two years.

“This is not a quick one-and-done support service. This is really an investment in the child care provider, the program and in meeting the social-emotional needs of the child or children,” Bhatia said.

The state is also working on its Early Childhood Suspension and Expulsion Reduction Project, which aims to better understand and prevent these practices. Healthy Minds Healthy Children, Bhatia said, is one such resource.

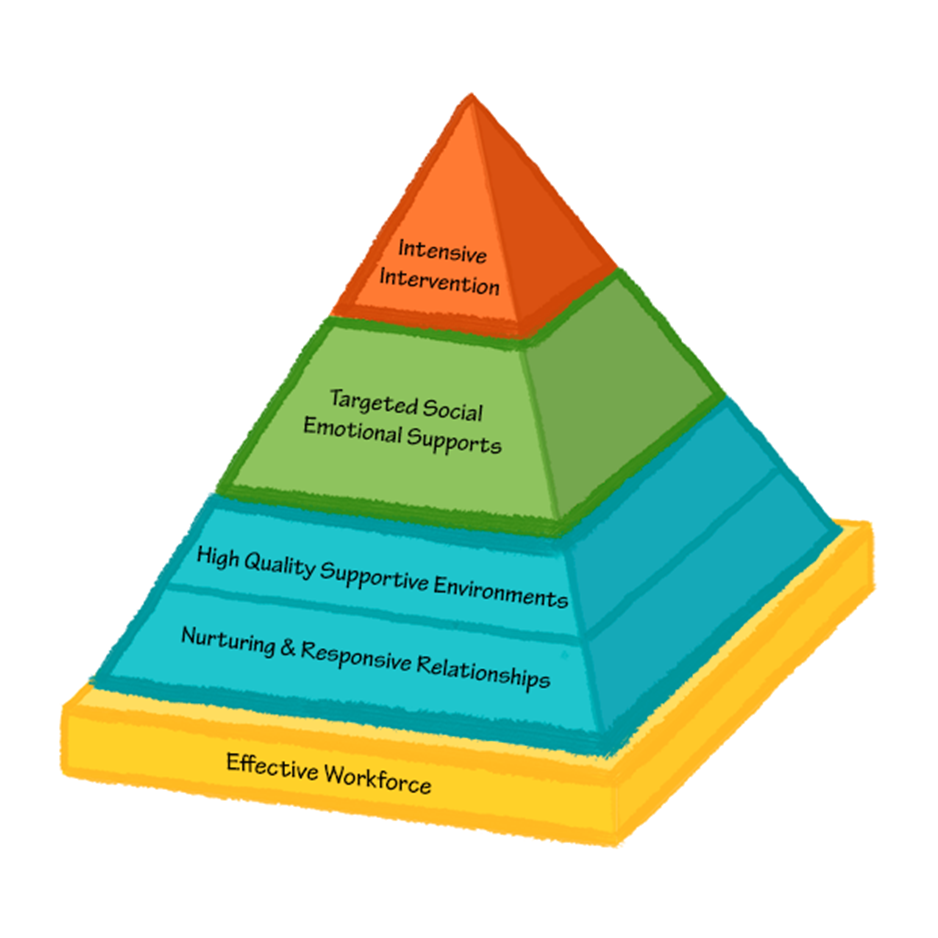

But it isn't the only statewide effort. In 2009 through grant help, Wisconsin adopted the Pyramid Model, a comprehensive framework that supports teachers in building social-emotional skills in children such as how to play well with others and regulate emotions.

Since then, studies have shown the efficacy of the framework — and many early learning programs across the state, including Bridges and Encompass’ centers, are championing it.

In fact, programs that implement the model see expulsion rates 13 times lower than statewide program expulsion estimates, according to WI-AIMH's 2022 report.

Behavior Help Pilot Program coaches adults in helping children work through behaviors

A few months ago, while the other toddlers at child care laughed and ate breakfast with their peers, Shawn and Sydney Smith’s then 3-year-old son sat alone.

It’s not that he wanted to be separate, but he felt he had a moral obligation to sit apart.

“I’m sitting here to keep my friends safe,” he told an inquiring adult.

The Smiths, from south central Wisconsin, glow when talking about their son: he’s big-hearted, adventurous and a doting older brother. At child care, his behaviors were more extreme than at home — hitting, scratching, biting. He’d then be scolded or removed from the classroom, his parents said.

Eventually, he started saying things like “I’m a bad kid, I do bad things” and “What is wrong with me?”

“Things like that, as a parent, just crush you,” Shawn said. “He’s not (a bad kid), he’s a great kid. He just needed some guidance on how to handle his emotions.”

The Smiths enlisted the help of the local school district, and eventually found Behavior Help Wisconsin, a suspension and expulsion reduction program currently operating in select counties thanks to funding from the Wisconsin Partnership Program at the University of Wisconsin. Soon, Briana Kurlinkus, a behavior coach with the program in Dane County, visited the boy at his child care center.

But it didn’t matter that help was on the way. A few days after this initial meeting, the Smiths' son was suspended.

Once the Smiths' son started at a new program, Behavior Help’s support followed. Within a few months, Shawn said they saw a “night and day” difference. Instead of negative self-talk, the now 4-year-old recites positive affirmations. His friendships are flourishing, and his outbursts are rare.

“It’s almost like his true personality was hanging dormant, and it just bloomed once he was able to be himself and he had the tools to be successful,” Sydney said.

While Kurlinkus said Behavior Help is not considered an IECMHC program, both interventions share a common principle: the importance of working with the adults in a child’s life. In Behavior Help’s case, behavior coaches work with a child's family and child care provider to equip them with the tools, knowledge and skills to reduce challenging behaviors and ultimately prevent suspensions and expulsions.

“I can’t come into this and simply just focus on the child. I can’t come into this and simply just focus all my efforts on the teacher and (classroom) environment," said Kurlinkus. "It’s also, 'How do we fit those parents or caregivers — who are the most important people in that child’s life — into the equation?'"

Behavior Help coaches observe the children they work with in their classroom, simultaneously assessing, and later working to boost, the mental health of the environment. This includes supporting teachers on their own mental health journeys, largely by helping to build their self-awareness and identify when they need to seek support. Kurlinkus often models strategies that they can use to curb challenging behaviors.

“We know that mental health is really important, and if a teacher’s mental health is in a bad place, and if the environment's health isn’t in a good place, that’s usually 99.9% of why children exhibit those challenging behaviors,” Kurlinkus said.

At the same time work is going on in the child care center, Behavior Help is assisting at home. In the Smiths’ case, Kurlinkus provided activities to help the boy manage and verbalize strong emotions, and is just a call away in case concerns arise. Sometimes, Kurlinkus does home visits with families she works with, helping to foster consistency between the classroom and home.

Once a month, Kurlinkus, the Smiths, and the child care center meet to discuss progress, goals and if any changes can be made to better support the child.

More: Your child needs mental health counseling. Get ready to wait weeks, with no guarantee of a good fit.

The Smiths’ experience is just one of the program’s success stories, according to Kurlinkus.

“We’ve been able to keep a lot of children in their programs, and we've had a lot of centers change policies, procedures and practices in order to support these children, which has been phenomenal," Kurlinkus said.

Time, money create barriers to intervention efforts

Any intensive trainings or program initiatives take time and money — two elements not on the early care and education industry’s side.

It can be hard for programs to justify these added expenses since educators often leave when a better position presents itself, usually at a school district where pay is higher and benefits are often included.

Such is the case with Hidde, Bridges’ now former behavior specialist. Recently, Hidde got an offer from the Oshkosh Area School District that she couldn’t pass up. Even with grant help, which enabled Desten to create the position, Bridges could not compete with the school district's wages and benefits.

“I often lose employees simply because we cannot offer higher wages,” Desten said. “At some point, money does matter, even when doing work you love.”

Advocates warn the financial struggle of child care programs across the state is about to get even worse, as Child Care Counts, a pandemic-era financial support credited with keeping thousands of child care programs afloat, is set to end in early 2024.

The fiscal cliff makes it more difficult for centers to create — or maintain — high-level behavioral health supports.

Given child care programs are strapped for funds, programs like Healthy Minds Healthy Children and Behavior Help, which provide free support to providers, can make a big difference. But, at the same time, many such programs have their own fiscal constraints.

For example, Healthy Minds Healthy Children must take into account the pandemic-relief funds that make it possible expire July 1, 2024. DCF Communications Director Gina Paige said future funding will depend on an “all-hands-on-deck” approach, which could potentially mean “braiding together public and private dollars.”

Resources for child care programs and families

Wisconsin Alliance for Infant Mental Health promotes mental health of infants and young children — wiaimh.org

The Power of Connection: WI-AIMH affiliate that has resources for families — the-power-of-connection.org

Pyramid Model — Wisconsin Alliance for Infant Mental Health (wiaimh.org): Learn more about the Pyramid Model — wiaimh.org/pyramid-model-home

Wisconsin Department of Children and Families Inclusion Resources/Tip Sheets: resources for providers and parents to promote inclusion and best support children with special needs — bit.ly/DCFinclusionresources

Kindness Project Resources, Community Early Learning Center Fox Valley: Access to the Kindness Curriculum, related materials and activities — https://bit.ly/CELCKindnessProject

Child Guidance, My YoungStar Connect: Resources on a variety of topics, from preventing early care expulsions and suspensions to inclusive practices — bit.ly/YoungStarchildguidance

Project Implicit: Three tests assess implicit bias on a variety of factors, including race, gender, sexual orientation, health and more — http://tiny.cc/f7davz

Cox Campus, Rollins Center for Language & Literacy: Free anti-bias training for early educators — https://coxcampus.org

Wisconsin Office of Children's Mental Health: Parenting resources, including a video on Responding to Challenging Behaviors of Children — https://bit.ly/OMCHresources

Head Start Early Childhood Learning and Knowledge Center: overview of early childhood expulsions and resources for teachers — bit.ly/HeadStartexpulsionsresources

National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC): Overview of national data on early childhood suspensions and expulsions, resources — bit.ly/NAEYCexpulsions

This story is part of the NEW (Northeast Wisconsin) News Lab's fourth series, "Families Matter," covering issues important to families in the region. The lab is a local news collaboration in northeast Wisconsin made up of six news organizations: the Green Bay Press-Gazette, Appleton Post-Crescent, FoxValley365, The Press Times, Wisconsin Public Radio and Wisconsin Watch. The University of Wisconsin-Green Bay’s Journalism Department is an educational partner. Microsoft is providing financial support to the Greater Green Bay Community Foundation and Community Foundation for the Fox Valley Region to fund the initiative. The mission of the lab is to “collaborate to identify and fill information gaps to help residents explore ways to improve their communities and lives — and strengthen democracy.”

READ THE SERIES:

Week 18: Wisconsin preschoolers are 5 times more likely to be expelled than K-12 students, but why?

Week 18: Pandemic, aftermath add more stress to Wisconsin early childhood teachers' mental health

Week 17: Breaking the cycle: Local building projects, state aid helping some reclaim 'the American dream'

Week 15: Breaking the cycle: Here's why pathways to higher education are vital for first-generation students

Week 14: With 'Silver Tsunami' on the horizon, condition complaints at senior living facilities surge

Week 13: Wisconsin foster children often need mental health care to thrive. Why is it hard to help them?

Week 12: Breaking the cycle: Intergenerational trauma has real impacts on lives, connections of Wisconsinites

Week 11: Rising cost of living in northeast Wisconsin has many working families treading water

Week 8: One in 5 could have dyslexia, but Wisconsin students, parents feel school support falls short

Week 7: Breaking the cycle: Addressing generational patterns key to improving quality of life

Week 6: It takes a village: How collaboration helped a small northern Wisconsin city add crucial child care

Week 5: Wisconsin families matter. Here's how 6 newsrooms, 2 community foundations and Microsoft aim to help

Week 4: Many kids missed dental care during the pandemic. Luckily, these dentists visit schools for free

Week 1: The new Wisconsin family? 1.7 kids, no picket fence and child care costs more than college

Natalie Eilbert covers mental health issues for USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin. She welcomes story tips and feedback. You can reach her at neilbert@gannett.com or view her Twitter profile at @natalie_eilbert. If you or someone you know is dealing with suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or text "Hopeline" to the National Crisis Text Line at 741-741.

Madison Lammert covers child care and early education across Wisconsin as a Report for America corps member based at The Appleton Post-Crescent. To contact her, email mlammert@gannett.com or call 920-993-7108. Please consider supporting journalism that informs our democracy with a tax-deductible gift to Report for America.

This article originally appeared on Green Bay Press-Gazette: Wisconsin childcare providers try to reduce expulsions, suspensions