This Wisconsin woman worked on the Manhattan Project, but you won't see her in Oppenheimer

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

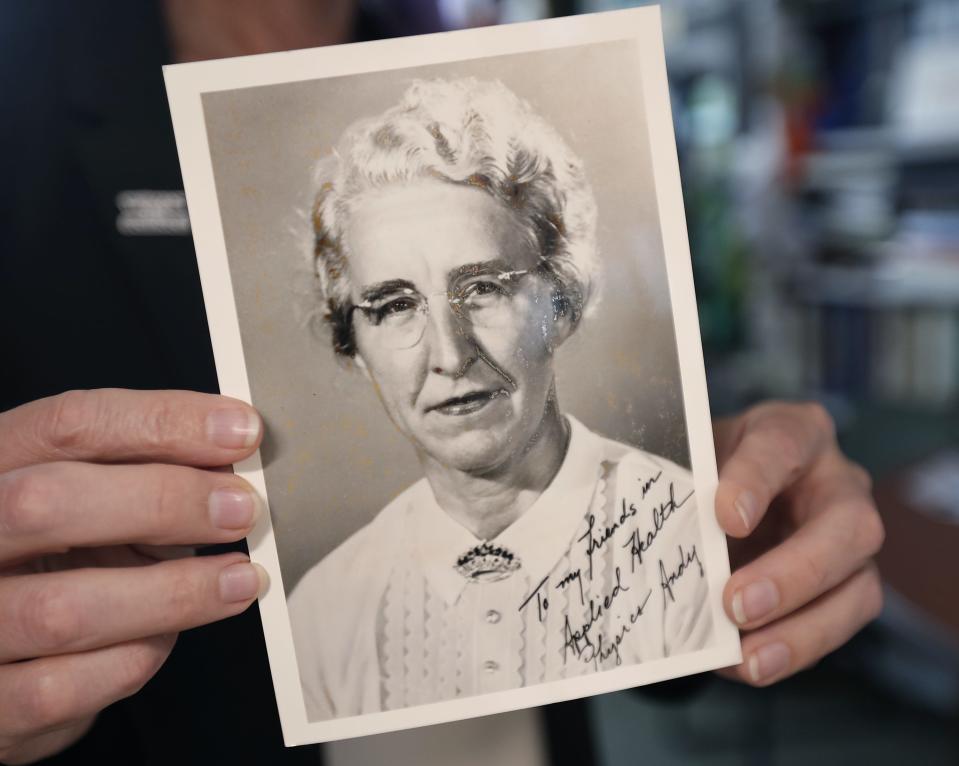

Elda Anderson wasn’t a big personality; she did her work and looked out for the people around her.

“That sounds so Midwestern to me,” said Megan Pickett, a Lawrence University professor. “That really is perfect Sconnie.”

Movies aren’t usually made about the hard-workers who keep their heads down. More often, movies are about the people who earn titles like “father of the atomic bomb.”

Christopher Nolan’s new film, "Oppenheimer," has been drawing people to theaters, including Pickett, to see the story of a lead scientist for the Manhattan Project during World War II. The project led to the creation of nuclear weapons.

Anderson was “critically involved” in the Manhattan Project, Pickett said, but then she became a hidden figure.

A physicist herself, Pickett is motivated by how little people remember Anderson.

“When you have someone like this who deserves to be known as our Midwestern Marie Curie, it makes me want to get her story out even more,” she said.

More specifically, Anderson is the Wisconsin Marie Curie. Her work as a scientist took her across the country, but she never forgot her roots, Pickett said.

Bringing 'Andy' back from obscurity

When Pickett, an associate professor of physics, earned tenure in physics in 2010, a university archivist told her she was the first woman in Lawrence’s history to do so.

But, if you include Milwaukee-Downer College — a former women's college that merged with Lawrence in 1964 — Pickett is really the second.

Anderson, who went by "Andy," was the first.

Learning this catalyzed Pickett’s mission of sharing Anderson’s story. The first step was finding details about her life.

An online search only yields a basic framework.

So, Pickett sent Freedom of Information Act requests to Los Alamos, Oak Ridge and Princeton University, hoping to piece together more of Anderson’s research and professional life. She has a few boxes of records to sift through, but is still waiting on the rest of the files.

In the spring, Kim Kearfott reached out to Pickett, after she heard about her efforts, to write a biography on Anderson.

Kearfott, a professor at the University of Michigan, won the Elda E. Anderson Award from the Health Physics Society in 1992.

The two now work together to preserve Anderson's history. Pickett has stacks of cassette tapes on her desk from Kearfott with interviews of people who knew Anderson. Some of them knew her at Los Alamos, others are family or friends.

The project is still taking shape, but Pickett and Kearfott see a part of themselves reflected in Anderson’s story.

“The three of us are three different generations of women in physics, coming up and working at different times and different areas,” Pickett said. “So, I think there’s some powerful messaging about who does physics, who tells the stories of physics, whose stories get to be told in the end.”

The award Kearfott won from the Health Physics Society is one of the few ways Anderson’s life has been memorialized. There was a full-page obituary for her in a physics magazine, Pickett said.

Otherwise, there are no monuments or statues or benches that Pickett has been able to find. The only physical reminder of Anderson's life — outside of her gravesite in Green Lake — is a brick paver on the Iowa State University campus in its Plaza of Heroines.

“She was well known in her time, and then she slipped into obscurity,” Pickett said.

From Menasha High School to the Manhattan Project

Anderson was born in 1899 in Green Lake. She had a sister who was one year older, and they remained close throughout their adult lives, from what Pickett has been able to find.

But Anderson had somewhat of a complicated family life otherwise.

Her mother was a nurse, but her father left the family when Anderson was quite young. Pickett said it was a “big scandal” because her father ran away with the local doctor’s wife.

Anderson had interest in math and science, which was piqued by her time at Ripon College and later the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she got both a master’s degree and PhD in physics.

Although a scientist, Anderson also spent time teaching. She worked at a junior college in Iowa and later taught at Milwaukee-Downer College — where she was often photographed wearing an oversized fur coat — before it merged with Lawrence.

As a teacher, Anderson was “no nonsense, but also extremely available to her students,” Pickett said. It’s the care that Anderson had for her students that attracts Pickett to her story.

Having taught during the Great Depression, there are plenty of stories about Anderson helping her students monetarily or talking with them about their troubles over a beer.

But it wasn’t just higher education. Anderson worked as a teacher at Menasha High School and is believed to have been the principal at some point.

A current secretary at Menasha High School, Brigid Gifford, found records of Anderson’s time in an old yearbook: “The physics and chemistry classes were made more instructive by various visits to paper mills, filtering plants and gas plants. These visits were made possible by the efforts of their teacher Miss Elda Anderson.”

After about 20 years at Milwaukee-Downer, Anderson was recruited to Princeton University to work in the war department’s research and development division. It was here that she was recruited to work at Los Alamos for the Manhattan Project in the 1940s.

More: Barbie's Dreamhouse might be in Malibu, but she has Wisconsin roots

Anderson's contributions to the Manhattan Project: Refining uranium, calculating cross sections

Anderson was hiking in Colorado when the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. She wasn’t bothered to hear about whether they worked.

She knew they would. She helped create them.

Anderson was recruited in 1943 to work on Project Y at Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico.

She refined uranium and helped calculate what Pickett said are called "cross sections." The way Pickett described it, calculating cross sections determines how likely it is that a neutron will hit a uranium nucleus and if it’ll have enough energy to split it apart.

If done incorrectly, Pickett said, it wouldn’t be possible to engineer the bomb.

“She was critical to making not only the bomb work, but any future work on being able to have a sustained reaction,” Pickett said.

What has become clear to Pickett in her research on Anderson is that she was “an exactingly precise scientist.” That may not seem like a difficult feat with today’s technology, but she was working on these projects without the help of modern computers.

As a fellow physicist, Pickett said she finds the precision of Anderson’s handmade measurements “compelling.”

But working at Los Alamos was really just the beginning for Anderson.

Helping with the atomic bomb led Anderson to create a new subfield of physics

Rather than spending the rest of her career touting her accomplishments at Los Alamos, Anderson studied the implications atomic bombs and the Manhattan Project could have on the world.

“The last part of her career was spent not just talking about the ill effects of the weapon we designed, but what do we do now that we made this,” Pickett said.

In 1947, Anderson went to the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee. She spent the next 15 years developing a new subfield of physics called health physics.

She looked at the effects of radiation on a person’s health. She created protocols for people handling radioactive materials — some of which Pickett said are still used today.

“She may not have been as tortured an individual as Oppenheimer was, but she had a deep conscience of what her job was and how it impacted people around her,” Pickett said.

More: How did they come up with 'Sandy Slope' for Appleton's new school? Here's the history

Reach AnnMarie Hilton at ahilton@gannett.com or 920-370-8045. Follow her on Twitter at @hilton_annmarie.

This article originally appeared on Appleton Post-Crescent: Oppenheimer link: Wisconsin woman worked at Los Alamos on atomic bomb