Wisconsin's oldest Methodist congregation closes due to high bills, low turnout. It's a familiar story nationwide.

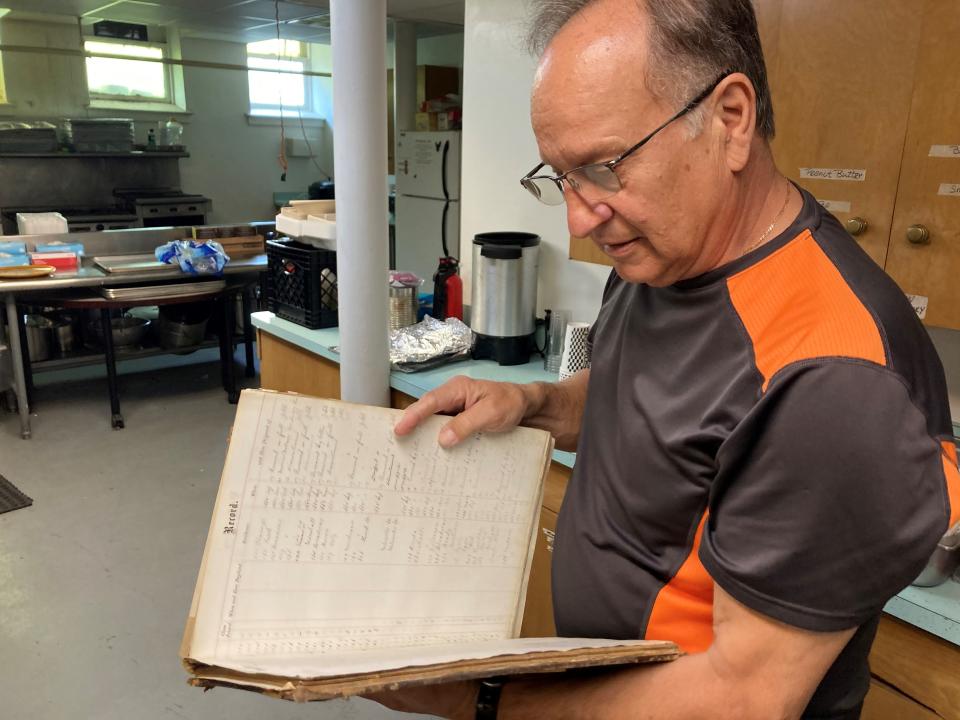

With the weeks winding down to Summerfield United Methodist Church's final Sunday service, longtime member Bob Sarsfield unlocked a safe in the basement and pulled out a book of marriage records.

They dated to 1874.

There, in tiny cursive script, were dozens of names of people married at Summerfield a century and a half ago, their addresses and occupations and wedding dates detailed in neat columns.

“This is the stuff they want us to turn in,” Sarsfield said.

The United Methodist Church had made the all-but-inevitable decision to close Summerfield’s doors for good. Sarsfield and another dedicated member, Marcia Tremaine, were cleaning out cabinets ahead of the final day in late June. The book was a peek at the long history of a once-vibrant congregation that in recent years had lost steam.

It’s a scene that has become familiar around the country. Researchers estimate that before the COVID pandemic, 75 to 100 houses of worship closed each week in the U.S., facing the same headwinds as Summerfield: aging and dwindling congregations saddled with insurmountable upkeep costs.

Churches that are thriving today tend to offer modern services and programming.

Summerfield, the oldest Methodist congregation in Wisconsin, had shrunk to only 11 members, none under 65 years old. The historic building at North Cass Street and East Juneau Avenue, constructed in 1904 as the successor to Summerfield’s first church, needed extensive repairs.

“We could continue going on a little bit longer, but you’re looking down this dark hole and it's just getting deeper and deeper,” said Sarsfield, chairman of the church’s trustees committee.

It was a quiet end for a church that was known for service to the community. Summerfield was the birthplace of Goodwill Industries of Wisconsin and held some of the city’s first Narcotics Anonymous meetings. For the past dozen years, members served hot meals several times a week to the homeless and hungry.

Extensive damage would cost more than $1 million to repair

Those who gathered in Summerfield’s sanctuary for its last service June 25 worshiped amid some of the church's obvious problems. Patches of drywall were discolored; paint peeled away. Half the large, stained-glass window on an internal wall was unlit, the lightbulbs burned out and not worth replacing. The massive, oblong, stained-glass skylight was speckled with dirt.

But the most widespread damage was elsewhere. In the fellowship hall as well as in meeting rooms, upstairs offices and closets, ceilings dipped from water damage, their tiles darkened or gone altogether. Most walls had a crinkled – if not shredded – appearance. Electrical wiring wasn't up to code.

In the balcony, a chipped rose window overlooked an array of dollhouses, toy blocks and baby cribs, a reminder that the congregation used to count children in its flock.

Sarsfield, who worked on jet planes’ electrical systems in the Navy and fixed farm equipment growing up in Iowa, has been playing a losing game of handyman whack-a-mole. He even put on a new roof at one point.

Repairing all the stained glass would’ve cost $250,000, Sarsfield said. The death knell came when an expert hired by the local district of the United Methodist Church estimated all the repairs — the water-damaged walls, the sagging ceilings — at $1.3 million.

The utility costs – including pricey steam heating – and the salary of the pastor, who split time with another church, exceeded the Summerfield's entire annual income of $25,000.

Church members talked about getting a loan from the Church, but repaying the loan would cost $78,000 each year, beyond Summerfield's reach. They also could have tried to rent out the adjacent unused pastor’s house, but its roof is leaking.

“If we had a larger membership, it would be different," Sarsfield said. "But it’s not.”

More: Wauwatosa Catholic School will close at the end of the school year due to low enrollment

More: 43 Wisconsin congregations are set to leave United Methodist Church over LGBTQ issues

Pandemic was turning point in long membership decline

When Kenwood United Methodist Church, across from UW-Milwaukee, closed about five years ago, several of its members joined Summerfield. (Kenwood’s building is now home to Zao MKE Church, a startup church known for its LGBTQ inclusivity.)

At first, the Summerfield congregation hoped the infusion might help save the church.

Then the pandemic hit. When services went online in 2020, many never returned.

Although Summerfield was located on Milwaukee's east side, where many young adults live, it had trouble attracting or retaining any of them. Many followed the trajectory of marrying and moving out to start a family.

“It was sad, and it was inevitable,” said Alan Rank, a former Kenwood member who found Summerfield’s congregation to be warm and welcoming when he joined.

Widespread church closures remove services from community

Summerfield's neighborhood is saturated with churches, a legacy of America’s more churchgoing past.

Today, many churches around the country are facing the same challenges. Experts project that 100,000 church properties could be sold across the U.S. in the next several years.

Mark Elsdon is the executive director of Pres House, a Presbyterian campus ministry at UW-Madison, and an expert on church properties.

When churches fold and a developer buys the land, the social good the church was providing — meals for the homeless, for instance – is gone for good, Elsdon said.

Churches also offer a space for community gatherings that, say, the high-end apartments that take their place can’t. Girl Scout troops, neighborhood associations, Alcoholics Anonymous groups and more often meet in churches for free or a small fee, he said.

“Where is that all going to meet?” he said. “You can’t have an AA in a Starbucks.”

Elsdon is struck by the scale of church closures.

“You just look at a map of where all these churches are (in Milwaukee), and you imagine, 10 years from now, 20 years from now, a third to a half of them are something else. What does that do to those neighborhoods?” Elsdon said.

More: Why this order of Catholic sisters converted their Milwaukee convent into affordable apartments

Churches must accept the reality that fewer people attend services than in institutional religion’s heyday in the 1950s, he said.

“The buildings aren't suitable for the purposes that we need them now,” he said. “They were built to have big Sunday worship and Sunday school." Now, the way people are engaging with church communities is changing, and the use of the space needs to accommodate that.

With his organization, Rooted Good, Elsdon works with church leaders to figure out how to repurpose buildings — before it’s too late — in a way that aligns with their mission. Elsdon has seen church properties converted to affordable housing, a kitchen for marginalized youth, a business center to support entrepreneurs, a childcare co-op for Latina teen mothers and more.

“We need to adapt to what it means to be a faith community today,” he said.

Summerfield had an outsized impact on neighbors in need

Summerfield is a prime example of a church whose closure leaves a hole in the neighborhood.

In recent years, Summerfield’s small, devoted cohort of volunteers made an outsized impact. The meal program regularly served hot meals to about 50 to 100 people four times a week before the pandemic. In the last couple years, 30 to 40 received meals three days a week.

The basement hall was open daily as a warming center in winter and a cooling center in the summer. Members had showers installed and ran a clothing donation operation, giving hats, coats and gloves to people in need.

And Sarsfield traveled weekly to an Oconomowoc distributor of Brownberry bread to pick up about 300 loaves of bread, bagels and English muffins that the church set outside the building for people to take.

Most nights, Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous groups met in the church basement.

Marcia Tremaine, who along with Sarsfield volunteered at the church every day, joined about a decade ago after moving back to the Midwest from the Washington, D.C., area.

“I came here because they were doing something,” Tremaine said. “So many other churches say, 'Let’s pray about these people.'”

The final service drew about 35 people, including several former members and Methodist pastors from area churches. They shared memories of the church’s active role in the community and its welcoming feel.

Sheila Jackson of Hales Corners first visited Summerfield in 1995 when, as a student at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, the church invited her Filipino dance group to perform.

She soon got married at Summerfield and served as its program coordinator. In the 1990s, the church was lively, Jackson said, with 60 to 100 members and many events, from ice cream socials to Lenten soup dinners to weddings.

“Two words I can think of (for) this place: love overflowing,” Jackson said.

Demolition a heartbreaking proposition to longtime members

The future of the Summerfield building is uncertain.

The United Methodist Church may sell the property, or it may choose to demolish the building and put something like affordable housing in its place, said the Rev. Ebenezer Insor, superintendent of the Wisconsin Southeast District.

The property, located in the Yankee Hill neighborhood on a block that also includes a Subway restaurant and the nightclub Victor’s, could be attractive to developers, members think.

But they hold onto a sliver of hope it won’t be torn down.

The thought of destroying the stained-glass windows and other historic features is heartbreaking, Sarsfield said.

“If they decide to sell it and tear it down, I don't know if I’d ever want to drive by there again,” he said.

The building doesn’t have historic designation because, according to Sarsfield, it became ineligible when a wheelchair-accessible entrance was added, changing the look of the exterior.

The church’s pastor, Lynne Hines-Levy, doesn’t see any path aside from demolition.

“The building is in extreme disrepair and I don’t know that it’s salvageable,” she said.

After making some calls and asking for help, Hines-Levy got word the day before the final service that a Salvation Army chaplain she knew would run a meal program for the homeless once a week from the parking lot at Victor’s. It wouldn't be the same as Summerfield's meal program, but in a small way, its legacy of serving the community would continue.

“It’s not about in there, really,” Tremaine said, standing at the church entrance. “It is about what we have done for the people here in the neighborhood.”

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Milwaukee's Summerfield United Methodist Church closes amid high bills