WNC History: 'Moms' Mabley, from Brevard to Asheville to national prominence on the stage

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“One day (my grandmother was) sittin’ out on the porch. I said, ‘Granny, how old does a woman have to be before she don’t want no more boyfriends?’ She was about 106 then. She said, ‘I don’t know, honey, you gonna have to ask somebody older than me!’”

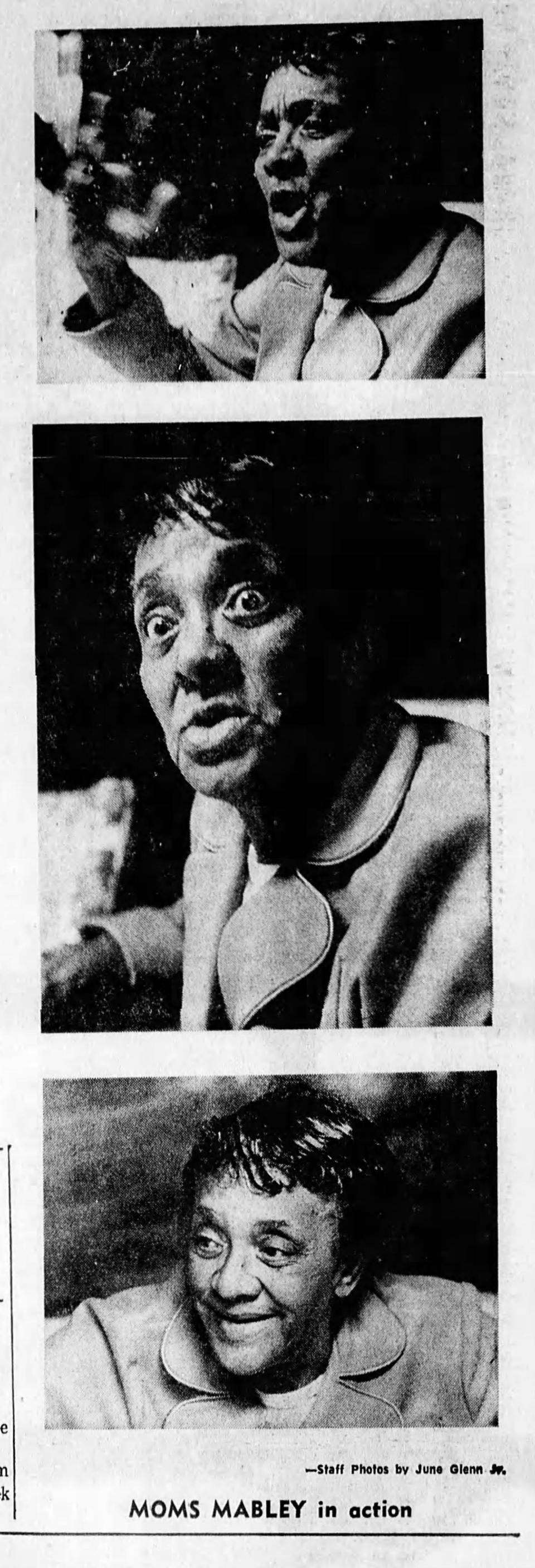

This joke was a standard for the popular actor and comedian who performed stand-up routines as “Moms” Mabley, a young-man chasing, old-man hating elderly woman, who wore flowered housedresses, droopy stockings and oversized shoes. One of her favorite lines was, “There ain’t nothing an old man can do for me but bring me a message from a young one.”

Moms arrived in Asheville near the end of October 1971 to perform at City Auditorium. Though she had been in show business for more than half a century, this was her first time performing in Western North Carolina, just 40 miles from where she was born and raised in Brevard.

She spent the morning before her Asheville show reminiscing about her childhood in the mountains with Eagle Street business owner Al Hutchinson. Much of the interview was published the following day in an article by Bob Terrell in the Asheville Citizen. The interview revealed many of the ways in which her early years in Western North Carolina were formative to her later success as a performer.

In 1971, as Moms traveled up the mountain into Asheville, she cried. “I couldn’t keep the tears back. My secretary said, ‘What’s the matter, Moms?’ and I said, ‘Oh, Lord, what a beautiful place God picked out for me to be born in.’”

Born in Brevard

One of eight children, Loretta Mary Aiken, who would later adopt the stage name Jackie “Moms” Mabley, was born March 19, 1897 in Brevard to Jim and Mary Aiken.

Jim had been born into slavery in 1861 to Mary Jane Aiken. As children, Loretta, her siblings, and her cousins “always wondered about (Jim’s) light skin.” One of Loretta’s cousins, Selena Robinson, remembered asking her grandmother, “How come Uncle Jim is so light and Daddy is so dark?” Mary Jane told her grandchildren that she would explain when they were old enough.

Selena recalled that years later, “she sat us down and told us that (Jim) was born by her boss (her enslaver, Benjamin Franklin Aiken), and that you couldn’t do anything about it then. You had to do what the boss said.” Mary Jane also told her grandchildren, “They let me keep my child and that made me so glad. And they never did beat me.”

Though little is currently known about Jim’s upbringing, by the time Loretta was born, Jim had become a well-known, well-liked, and very successful businessman in Brevard.

Despite discrimination and segregationist policies, Jim owned a large building on Brevard’s Main Street, which contained a cafe, barbershop and mercantile store. He ran a bakery and dray service, delivered mail, sold caskets and rented rooms in the Aiken family home to boarders. Because Brevard’s Black population was small, the majority of those who patronized Jim’s businesses were white.

Jim was also civic minded. He chartered the Mountain Lily chapter of the Masonic Order in 1905, held meetings above his store for the United Order of Odd Fellows, served on the committee governing the area’s school for Black children and volunteered as a firefighter.

More: WNC History: Bettie Sims was not a typical moonshiner

More: WNC History: Who was the dead swindler on a pedestal in an Asheville funeral home?

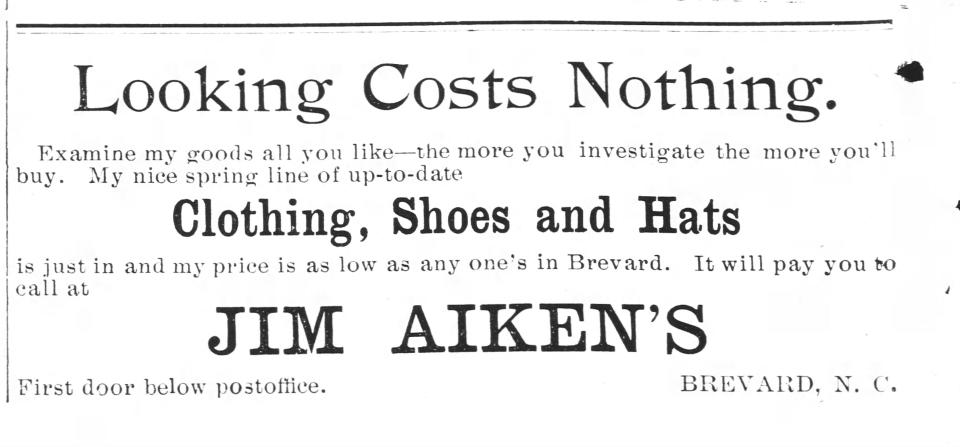

Loretta certainly picked up at least some of her sense of humor from her father. Jim ran numerous ads for his businesses in the local paper, many that illustrated the folksy, non-threatening sense of humor that Loretta would later employ in her act.

One 1904 ad stated, “looking costs nothing. Examine my goods all you like – the more you investigate, the more you’ll buy.” In a 1905 shoe ad that ran during the Russo-Japanese war, Jim joked, “Shoe news and new shoes at Jim Aiken’s. While the … Jap is fiercely fighting the … Russian in the Far East, I am just as bravely battling for shoe supremacy.” As Moms Mabley, Loretta would also use humor to comment on current social, political, and international issues.

Due to her father’s success, Loretta grew up in relative privilege. But, when she was 12 years old, a town firetruck exploded, killing her father. So many people, both Black and white, attended Jim’s funeral that it had to be moved to one of Brevard’s large white churches.

Staying in WNC

After her husband’s death, Loretta’s mother Mary had to petition to claim his property, and though she was eventually able to take ownership of their house and store, the family’s social and economic standing in the community was much diminished. Loretta’s mother did her best to keep the family afloat, but in the following years, Mary remarried and the couple moved north, looking for a better life along with six million other Black southerners during the Great Migration. Before she left, Loretta’s mother told her, “You’re too much like me not to be something.”

For the next few years, Loretta stayed in Western North Carolina. As a teenager, she was the victim of two sexual assaults that resulted in pregnancies. Her grandmother, Mary Jane, who had been raped by her enslaver, advised, “No matter what anybody does to you, don’t you ever hate them because hate will destroy you.”

Loretta later recalled sitting on Mary Janes’ front porch in Brevard, thinking that “where the mountains met the sky … was the end of the world.” That day, her grandmother encouraged her to see beyond the mountains. Loretta recalled her grandmother saying, “There’s a world out there. ... I want you to go out in it. I never had the chance … but I want you to go. Put God in front … and go ahead.”

Loretta did as her grandmother said. And, in 1971, remarked, “I’m still doing what she said. I put God in front and I went ahead. That’s my motto.”

During her first pregnancy, Loretta left Brevard for Asheville. At 14 years old, Loretta began serving as a wet nurse for an Asheville family. She later spoke about having to deny milk to her own baby, Lucretia, in order to feed her employer’s child, Lois. Loretta stayed in Asheville for about four years until being raped again, this time by a white sheriff.

With little money to support a child, Loretta planned to travel to Detroit for an abortion. She recalled, “Now I was brought up in a very Christian family and I wasn’t taught to throw away children, but I was going to … something told me not to. ... I got down on my knees and asked God to open up a way for me to make me and this child a living. Suddenly a voice came to me … and it said, ‘Go on the stage.” So rather than continue to Detroit, Loretta stopped to stay with her mother in Cleveland and make a plan.

It did not take long for her prayers to be answered. According to Loretta, her mother was boarding with a couple, Reverend Speaks and Mrs. Speaks. When Loretta arrived, she found that next door to the Speaks was a house where “show business people went to eat.”

Breaking into show business

One night, Loretta was invited over for dinner. She recalled, “Bonnie Belle Drew from Chicago was there at the head of a show and she asked me if I was a stage girl. I said no, but that I used to have the funny parts in the little plays we did in church, and she asked me if I wanted a job.”

“I thought about the dream, telling me to go on stage, and I said yeah, and she said they were leaving the next day and I said, ‘Oh Lord, Reverend Speaks would have a fit if he knew I was going on stage.’ She told me to throw my clothes over the back fence and she would put them in her truck, so I throwed what few I had over the fence and next morning left there.”

Soon she was in Pittsburgh and on the stage. “I could always dance, but I was pregnant, and they put me to doing a comedy part in a play called ‘The Rich Aunt From Utah.’” She traveled and performed with that show until she gave birth. (Though stories vary about what happened to her first two children, they were either given away as infants or left in the care of a woman who disappeared with them. Loretta would later go on to raise three more daughters and an adopted son.)

Loretta’s ties to her family continued to influence her throughout her career; she took the stage name Jackie Mabley when her oldest brother told her she “was a disgrace to the Aiken name because (she) went on the stage … (and) that stage women wasn’t nothing but prostitutes.” The real Jackie Mabley had been her fiance at one time. She joked to Ebony magazine in a 1970s interview that the male Jackie had taken so much from her, it was the least she could do to take his name.

More: WNC History: Rumors of Babe Ruth's death after Asheville stop were greatly exaggerated

More: WNC History: Infidelity may have led to Guastavino's move here, work on Biltmore, basilica

As her popularity grew, she was able to find enough work in New York City to stop traveling the Chitlin’ Circuit (venues around the country where Black performers played to Black audiences). Now in the city permanently, Loretta as Jackie Mabley became part of the Harlem Renaissance. Contrary to her adopted persona of a “dirty old lady” chasing after younger men, she came out as lesbian in the late 1920s and was often seen around town with attractive younger women.

Until the 1960s, Moms Mabley played almost exclusively to Black audiences, beginning her act with the catch phrase, “I got somethin’ to tell you.” Then in 1962, she played Carnegie Hall to her first all-white audience. They loved her. She began appearing on TV variety shows — Flip Wilson, Ed Sullivan, and Merv Griffin, among others — reaching new audiences that had never heard her before.

At the same time, the civil rights movement was gaining momentum across the United States. Moms’ act became more and more political. White audiences listened. Her accessible and non-threatening persona allowed her to cover topics like ageism, sexuality, gender and racism without alienating her audience.

One popular Moms joke of the era went, “One of them big cops came running over to me and said, ‘Hey woman, don’t you know you went through a red light?’ I said, ‘I seen all you white folks going on the green light; I thought the red light was for us!’”

Her success continued into the 1970s. Shortly after the premiere of her first major movie ("Amazing Grace") in 1975, she began to think about making a movie about her own life, which she described as “one that I saw live, that nobody don’t know but me.” But on May 23, 1975, Moms died.

As the first female African American stand-up comedian, Moms opened doors for and inspired those who came after her. She often said in interviews, “There’s not a comedian in show business that hasn’t stole material from Moms. Not white or black. As fast as they steal ’em, God gives me some more.”

Despite her tremendous nationwide influence as a performer and activist, Moms Mabley’s ties to Western North Carolina are little known. In 1997, on what would have been her 100th birthday, the town of Brevard named the street she grew up on after Moms Mabley but quickly switched it back when the street’s residents complained about the unexpected change.

Finally, on Oct. 20, 2023, the NC Highway Historical Marker Program placed a marker recognizing Moms Mabley on Brevard’s Main Street identifying her not only as a pioneering Black comedian, but also as a social and civil rights activist.

Anne Chesky is the author of a number of local history books, including "Murder at Asheville's Battery Park Hotel: The Search for Helen Clevenger's Killer," which was a finalist for the 2022 Thomas Wolfe Memorial Literary Award.

This article originally appeared on Asheville Citizen Times: WNC History: 'Moms' Mabley, from Brevard to Asheville to the stage