State to add 250 contact tracers in Miami-Dade, but mayors say it is not enough

Tension among local, county and state officials over the spread of COVID-19 in Florida’s biggest hot spot, reached a peak Thursday when the mayors from some of Miami-Dade County’s most prominent cities called attention to the state’s shortage of contact tracing investigators in the county.

Not even a “happy” announcement from the county mayor — the hiring of 250 additional contact tracers, state health department employees who contact coronavirus patients to contain the spread of the virus — could blunt the sharpness of the attacks from local mayors, who gathered at Miami City Hall to take aim at Miami-Dade Mayor Carlos Gimenez and Gov. Ron DeSantis.

The current team of 300 contact tracers in Miami-Dade, which will be bolstered by the new investigators, is still insufficient to stem the spread of the virus in a county that has averaged 1,868 new cases a day over the past two weeks, the mayors said. They requested an additional 500 tracers.

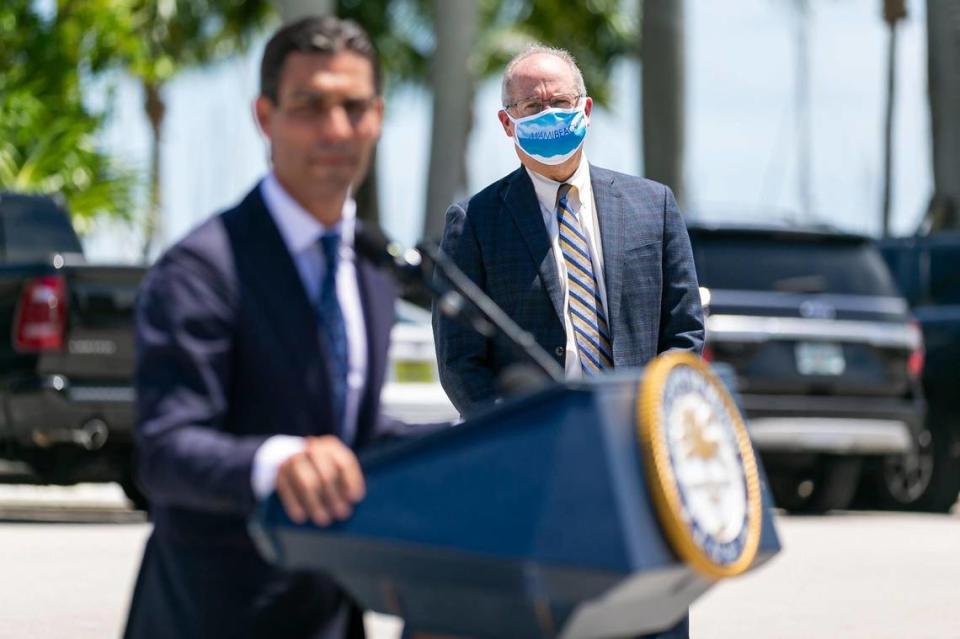

“The contact tracing program was fully unprepared for a surge,” said Miami Beach Mayor Dan Gelber. “Not even in the ballpark of prepared. Woefully unprepared.”

During a one-day sampling this week, the county’s contact tracers were only able to successfully reach about 17% of patients who had tested positive, Gelber said. Last month, state health officials told the mayors during a conference call their success rate was closer to 90%.

“The governor should be lying awake at night wondering who isn’t being reached,” Gelber told the Miami Herald. “This is a serious failure.”

Miami-Dade County has the state’s highest number of COVID-19 cases, with 55,961 confirmed infections to date.

Hours before the mayors’ press conference, Gimenez announced that the Florida Department of Health would hire an additional 250 contact tracers in the county. The county will pay for the extra workers using federal funds from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act.

In a press release, Gimenez said the county will use $14 million in federal grants received through the CARES Act to fund the additional workforce. The contact tracers will be hired by Maximus, a Virginia-based contractor, and they’re scheduled to begin working in Miami-Dade as soon as possible, according to the agreement.

Florida’s health department will pay Maximus at least $33.6 million — from the federal money — to provide contact tracers throughout the state, according to purchase orders published by the state’s Department of Financial Services. The first purchase order, for $6.2 million was signed on May 28. A second purchase order was signed on July 1 for $27.4 million.

State and county officials signed the agreement Thursday morning after DeSantis said in Miami on Tuesday that he has approved $138 million for contact tracing and other response efforts. Gimenez, who had been asking for more contact tracers for Miami-Dade since May, said at the time that he would defer to the state to expand contact tracing in the county.

“I’m very happy today that we are moving forward,” Gimenez said in the press release.

Gelber was joined Thursday outside Miami City Hall by Miami Mayor Francis Suarez, Miami Gardens Mayor Oliver Gilbert and Hialeah Mayor Carlos Hernández.

The coalition of local leaders highlighted the growing schism between city mayors, Miami-Dade County and the state. Suarez and Hernández urged Gimenez to open up a line of communication with the mayors in the county. Gelber took aim at the administration of Gov. DeSantis.

“The governor should be lying awake at night wondering who isn’t being reached [by contact tracers],” Gelber told the Miami Herald. “This is a serious failure.”

Miami-Dade would need 10,449 contact tracers or about 387 per 100,000 residents to effectively trace new COVID-19 cases, according to the Mullan Institute at George Washington University, which publishes a contact tracing workforce estimator.

The ability to set up “efficient” contact tracing is one of the preconditions of reopening local economies, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“According to industry standards, we must have 500 or more contact tracers in just our county, and we need them like two weeks ago,” Gelber said.

Negotiating for months

The Florida Department of Health and Miami-Dade officials have been negotiating since May on the number of additional contact tracers needed for the county and how much it will cost.

Miami-Dade plans to spend about $40 million in federal grants received through the CARES Act on contact tracing and testing, according to a presentation Wednesday at a meeting of county commissioners.

On Thursday morning, the health department confirmed an additional 1,987 new COVID-19 cases in Miami-Dade and a positive rate of 26.2% of all tests received Wednesday.

During a one-day sampling this week, the county’s contact tracers were only able to successfully reach about 17% of patients who had tested positive, Gelber said. Last month, state health officials told the mayors during a conference call their success rate was closer to 90%.

“That means that almost nobody is being contacted right now,” he said. “We are unable to contain the spike because we have nobody doing what they said they would be doing.”

The state has not shared contact tracing data with city leaders, Gelber said. Without data to show where a majority of the spread has occurred and to identify specific events and locations where people were infected, South Florida leaders say they have been unable to launch an effective response.

“It has felt like we are flying blind because we’ve not received data points that would allow us to deliver directed countermeasures,” he said. “We don’t want to respond to spikes with a chain saw, we’d rather use a scalpel. If we don’t know where the spikes are coming from — what industries, what food stores, what regions, what occupations — then it’s hard to limit the response.”

Gathering additional data

Amid pressure from local officials, the health department in Miami-Dade on Monday amended questionnaires that contact tracers administer to patients to include information about possible exposure settings. Before, contact tracers would only ask patients in what city or county they were residing in the weeks leading up to their diagnosis.

“We have implemented this survey late afternoon yesterday,” said Dr. Yesenia Villalta, the health department’s administrator in Miami-Dade, in an email to Gelber on Tuesday. “I have asked my contact tracers/investigators to continue to use this survey with the cases moving forward.”

Miami Mayor Suarez, who contracted COVID-19 in March, said while it will be useful in the coming weeks to have contract tracers ask more detailed questions that could help show where people have been exposed to the virus, the more precise data is too small of a sample size this week to make smart decisions.

“The volume of data is not enough,” he said.

Part of the problem, health officials told the mayors, is that some people who answer the phone do not want to answer the questionnaire. But the Florida health department has not launched a high-visibility campaign of public service announcements to educate residents and alert them that they may receive a call from a contact tracer.

Pinecrest Mayor Joseph Corradino, who is on the executive board of the Miami-Dade League of Cities, said that issue compounds the dearth of contact tracers.

“I think there is a cooperation issue,” Corradino said. “Even if we had the right questions on the form, even if we had the right amount of data, there are still people that aren’t being honest with the contract tracers or they’re not answering the phone. That’s going to make it harder for the government to make laser-focused policy.”

Rep. Shevrin Jones’ experience

One Florida legislator with COVID-19 was interviewed by a health department contact tracer in Broward County this week, and he said the state’s program has been hit and miss.

The day after he tested positive for COVID-19 in the emergency room of Memorial Regional Hospital in Hollywood on July 1, state Rep. Shevrin Jones, D-West Park, got a call on his cellphone from a woman who identified herself as an employee of the state health department.

Jones, 36, said the woman asked him two or three questions before the call disconnected. The call lasted about eight minutes, Jones said. She got his name, and asked whether he had been in a car with anyone recently.

“I don’t think she was clear on her role as a contact tracer, personally,” Jones said. “You could tell she was just reading off a questionnaire, and by the time she got to question three, the phone disconnected and she never called back.”

Four days later, on July 6, Jones posted a message on Twitter about the experience. He called the contact tracer “unprofessional” and noted that she never called him back.

That same day, Jones learned that his 71-year-old mom and his 74-year-old father also had tested positive for COVID-19, though he said they have been mostly asymptomatic.

On Tuesday, Jones appeared on CNN’s morning program, “New Day,” where he told the show’s anchor, John Berman, about the experience.

“Unfortunately,” Jones said on the air, “the contact tracing that we have here in Florida is a joke.”

That night — five days after he first received a call from the contact tracer — Jones got a second call from the health department. He said the caller was a man who identified himself as an epidemiologist for the state.

They spent about 30 minutes on the phone, Jones said. The epidemiologist asked Jones who he lives with, whether they had been tested, and if he had been around friends and family. Jones said the epidemiologist also asked about symptom history, then advised Jones to self-quarantine and promised to follow up on Friday.

“That’s how contact tracing should be happening, for people to find out who they were with, and these people can be quarantining and also going to be tested,” Jones said.

In addition to his parents getting COVID-19, Jones said his older brother, Derrick Jones, also tested positive for the virus. They get together every weekend, he said.

Jones said he doesn’t know where he got COVID-19. But he acknowledged that he had relaxed too much with friends, shaking hands and hugging, in the days before he first started to feel fatigued.

“I did let my guard down,” he said.

Jones is also campaigning for a seat in the Florida Senate, though he said there’s no canvassing or in-person interaction with voters. “It’s been mostly digital — phone calls, mailers.”

On Wednesday, Jones said he has been feeling better, though he still has bouts of coughing and fatigue. He has been keeping a video diary of his experience, too.

Jones said he has criticized the state’s contact tracing efforts on TV because Florida’s surging numbers of new COVID-19 cases are causing a lot of damage to people and the economy. He said he was pleased that the agency followed up with a more thorough interview after he did so.

“The faster we can do things right,” he said, “the faster we can get back to some type of normalcy.”