Wolf fight continues in Legislature with hearing for population quota for gray wolves

MADISON - Wisconsin legislators once again debated over whether there should be a quota for the number of wolves in the state, instead of a more flexible plan the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources proposes.

The Senate Committee on Financial Institutions and Sporting Heritage Thursday afternoon heard testimony about the proposed quota, only weeks ahead of a DNR public hearing on their proposed management plan.

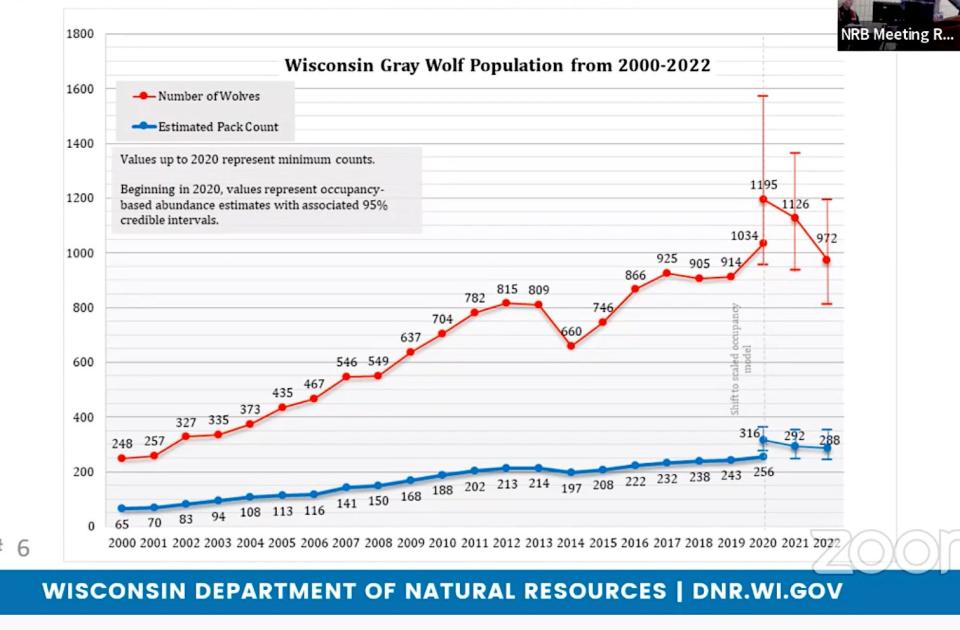

The agency's plan would likely keep the state's wolf population between about 800 and 1,200 animals, or about the number found in the state in recent years, according to documents released to the public in August.

The DNR has been working on a new wolf management plan "in earnest" since early 2021.

The initial draft was released Nov. 10 last year; about 3,500 public comments were received through Feb. 28.

More: Smith: The DNR is updating wolf hunting and trapping rules, including a shorter kill reporting time

The first draft focused on "adaptive management" in geographical zones and did not specify a statewide wolf population goal. Both aspects are consistent with the state's widely supported black bear management plan.

Although DNR social science surveys in 2014 and 2022 found majority support among Wisconsin residents for the "current number or more wolves," some Wisconsin legislators have pushed to set a much lower statewide wolf population goal of 350 animals.

Wisconsin had 972 wolves in 288 packs in late winter 2022, according to the most recent DNR estimate.

The DNR's draft plan sets six key objectives: Ensure a healthy and sustainable wolf population to fulfill its ecological role; address and reduce wolf-related conflicts; provide multiple benefits associated with the wolf population, including wildlife watching and a public hunting and trapping season; increase public understanding of wolves in Wisconsin; conduct scientific research to inform wolf stewardship; and provide leadership in collaborative and science-based wolf management in Wisconsin.

But Republicans are pushing a new bill that would change the DNR's planning process in regards to wolves.

More: Updated Wisconsin wolf draft plan steers clear of population goal but 800 to 1,200 likely

Senate Bill 139, introduced in March, would require the state to have a firm population goal instead of the agency's "adaptive management." The authors of the bill did not offer a number, though.

"I would like to listen to all stakeholders," said Rep. Chanz Green, R-Greenview, one of the authors. "I think we could sit down with all the stakeholders and get everybody's input. That would be more appropriate."

Supporters of population goal say it gives 'a clear target to aim for'

Those who testified in favor of the bill said it would help the state more accurately administer a wolf hunt.

Luke Hilgemann, the executive director of the International Order of T. Roosevelt, said that population goals have been responsible for the success of wolves in both Wyoming and Alaska.

"It would give our conservation efforts a clear target to aim for and would help to ensure the survival of the wolf population in our state," he said during testimony. "It would also provide a benchmark against which we can measure our progress and adjust our strategies as necessary.

More: Final two Natural Resources Board members questioned by Senate committee

Scott Goetzka, the vice president of the Wisconsin Game Preservation Association, shared stories from the Northwoods of how wolves have gotten into deer preserves or interrupted bird hunting by encroaching on hunters and their dogs.

"We're hoping we can get some kind of numbers set up so that they can start to reduce the wolf population, and more importantly, when they do cause bigger damage, you will be able to quickly dispatch them," he said. "By reducing the number, basically we will be able to take care of the wolves that are causing problems."

George Meyer, the executive director at Wisconsin Wildlife Federation and a former DNR secretary, said he dealt with this issue in the 1990s and is not surprised the conversation is ongoing. He said there is a need for a numerical standard because it's a better management strategy.

"It's not just the biological carrying capacity, but the social capacity, which means that everyone is listening to what's necessary to protect people being damaged by the species," Meyer said. "You can reduce the current numbers and most importantly, you won't have citizens damaged by a wildlife species you're supposed to manage responsibly."

Those who support adaptive management said that having a more flexible system could be more beneficial to ensuring the longevity of the state's wolf population.

Randy Johnson, a large carnivore specialist for the DNR, said that a static numeric goal could become ineffective over the long run.

"There are some significant challenges with determining what is the 'appropriate population number' that reflects the broad range of social preferences among the Wisconsin public, as well as the biological considerations of a dynamic wildlife population," he said during the hearing. "Further, a single statewide population goal may fail to consider the geographic distribution of wolves in the state."

Megan Nicholson, Wisconsin director of the Humane Society of the United States, said in written testimony submitted to the committee that wolves need to be managed by peer-reviewed science.

"Wolf populations do not need to be 'managed' to specific numbers through human intervention. Scientific studies show that wolf populations are generally limited by prey availability, as well as disease, human densities, terrain, and their own territorial and social nature," she said.

"Wolves don't need to be 'controlled' to an arbitrary numerical goal, but rather that goal for Wisconsin to have a self-sustaining, self-regulating and genetically diverse population that maintains connectivity with wolf populations in neighboring states and fulfills its ecological role."

Adaptive management vs. population goal

One main difference separates the two different types of wolf management: the ability for the DNR to take into account the size, distribution and other important circumstances relevant to the wolf population.

Johnson said in an interview that adaptive management means there's a chance to reevaluate each time there is a wolf hunting season in the state, and consider the positives and negatives of the wolf population.

"Adaptive management at its core is an ongoing process to try to find that balance and inherently takes into account differences and how those things play out in different parts of the state," he said.

The Legislature is asking for is a fixed number of wolves in the state, which wouldn't change unless there was another lengthy rule-making process.

"The idea would be that single goal would be the main driver behind setting harvest quotas, and if we're really far above the goal, we're going to have higher quotas," he said. "And if we're really close to that goal, we're going to have much smaller quotas. And if we're below the goal, that's a tricky spot to be in."

Laura Schulte can be reached at leschulte@jrn.com and on X at @SchulteLaura.

THANK YOU: Subscribers' support makes this work possible. Help us share the knowledge by buying a gift subscription.

DOWNLOAD THE APP: Get the latest news, sports and more

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Legislature hears bill to set population goal for wolves in Wisconsin