Woman didn’t know what killed her brother until she was diagnosed with the same disease

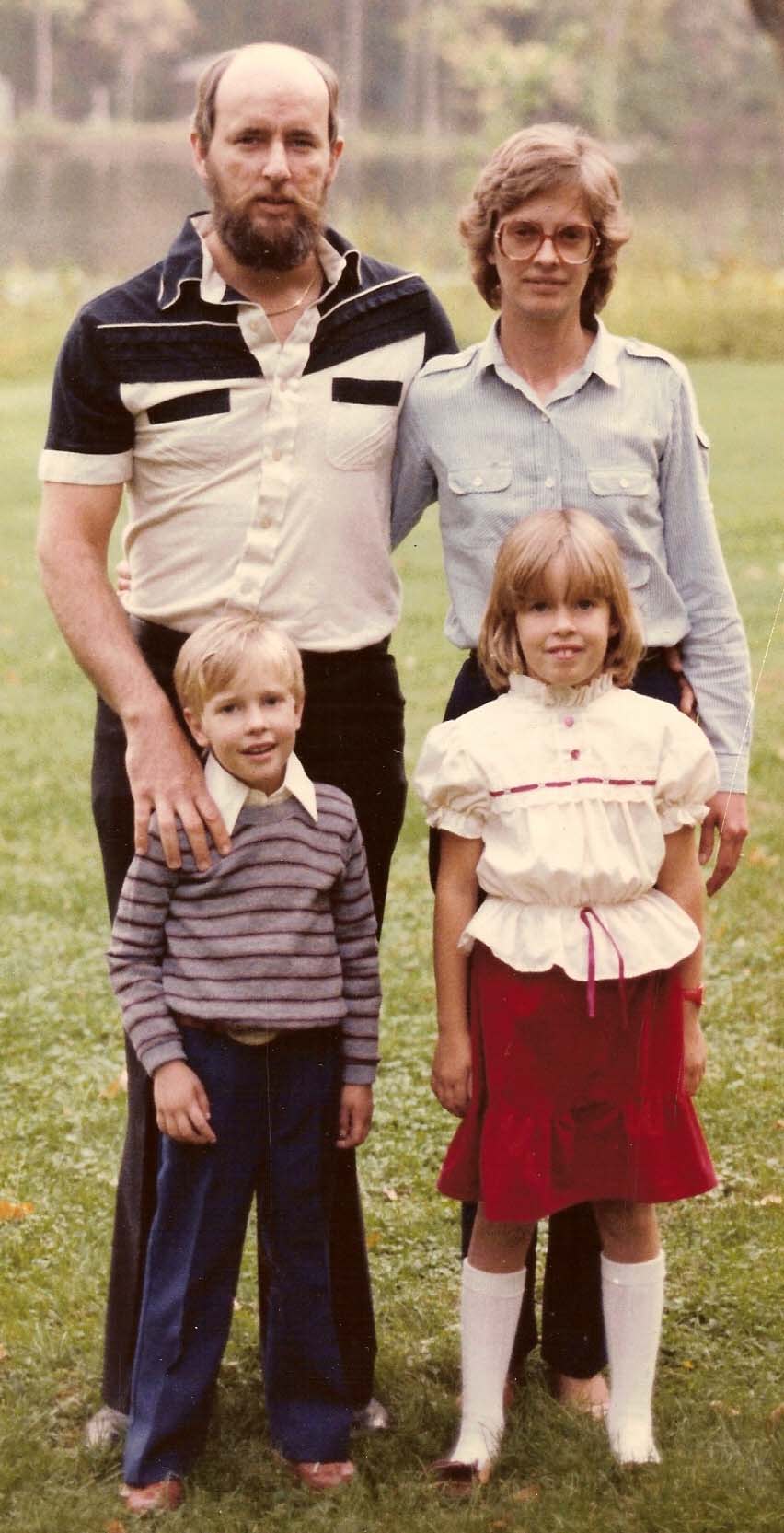

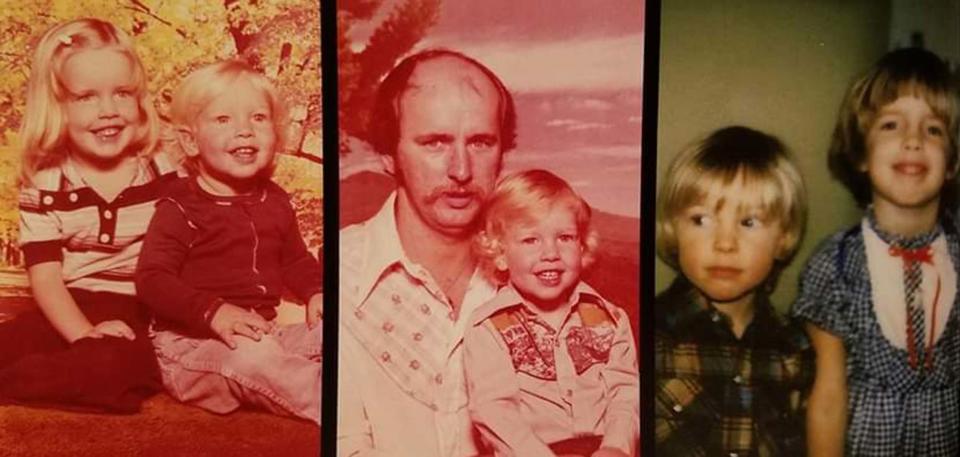

When Heather Kauffman was a child, her brother BJ died when he was 5 of what she thought at the time was a “rare lung disease.” For much of her life, she had no idea what it was and just knew that doctors didn’t have anything to treat it. In 2017, Kauffman began experiencing what she thought were panic attacks. After numerous tests, she learned what was causing this sensation: She had pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). When the doctors told the family, her parents immediately understood what it was.

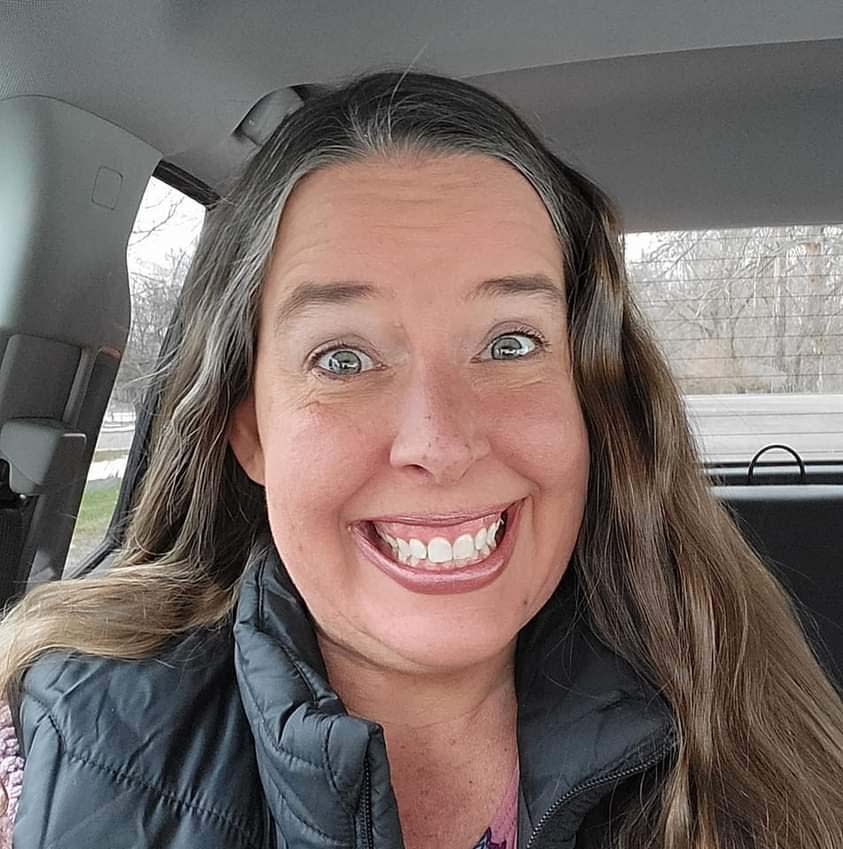

“My dad looks at me and he says, ‘We know what that is. That’s what our son died from, and I was mortified because I had no idea that’s what BJ had died from,” the 48-year-old from Charlotte, Michigan, tells TODAY.com. “Now I have something that I’ve watched my brother die of.”

Much had changed since her brother’s diagnosis, and she started taking numerous medications and even joined a clinical trial of a drug to treat PAH in August of 2021. She hoped that her participation would help her family and the lives of others with the condition.

“From the very beginning, I told (the doctors) I would do anything I could do to help (cure) this disease,” she says. “My parents lost one child and watching me go through it, I have to be able to make a difference for my sister and her three kids.”

Breathing problems lead to diagnosis

In 1982, Kauffman’s parents learned that their son had a lung condition. At the time, she was 7 and he was 5. Doctors didn’t really have much to help treat his condition.

“I remember them doing low sodium and things like that,” she says. “I really didn’t know a lot about the disease.”

Doctors told her parents that Kauffman shouldn’t be impacted.

“They were told at the time there was no genetic connection, and they didn’t need to worry about their living child,” Kauffman says. “If you would have asked me six years ago what my brother passed away (from) I would have said a rare lung disease. I had no idea the name of the disease.”

Because doctors told the family there was no genetic link, she never underwent testing or thought it could be something that affected her. Then in 2017, Kauffman was experiencing a lot of stress. Her husband was deployed to the Middle East, and she thought she was having “panic attacks.”

“I wasn’t breathing very well,” she says. “I didn’t think it was bronchitis, but I thought it was something.”

Doctors at urgent care worried it could be a blood clot and sent her to the emergency room. After an EKG, she was admitted to a small local hospital. Doctors ordered a follow up EKG and then an echocardiogram and she was transferred to a larger hospital.

“Initially it was water around my heart,” Kauffman says. “They gave me Lasix so the water reduced.”

That’s what allowed doctors to see what was really impacting Kauffman — pulmonary arterial hypertension. She texted her diagnosis to her parents, not knowing that PAH killed her brother. She later learned it takes years for a proper diagnosis. She began going to the University of Michigan for treatment, which included taking medications delivered by a pump. As her disease progressed, doctors thought she might need a lung transplant. But before that happened, she joined a clinical trial run by one of her doctors, Vallerie McLaughlin.

“In 2020, Dr. McLaughlin’s like, ‘There’s this new drug trial Stellar. We think you’re a great candidate,’” Kauffman recalls. “I said, ‘Let’s do it.”

Pulmonary arterial hypertension and clinical trial

Pulmonary arterial hypertension is a type of pulmonary hypertension, which is high blood pressure in the lungs.

“It comes from the very small blood vessels in the lungs and that can cause the resistance in the lungs to go up,” Dr. Vallerie McLaughlin, endowed professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Michigan Medical School, tells TODAY.com. “That causes the right side of the heart to have to work harder to pump against this high pressure and high resistance.”

She adds that the right side of the heart isn’t “big, muscular” like the left side and struggles to pump as hard. In some patients it can cause heart failure. The cause can be complex.

“Pulmonary arterial hypertension can be what we call idiopathic, there’s no reason for it. We can’t find anything,” she says. “There are some genes that can cause it.”

Drugs, such as methamphetamines, contribute to people developing it and it can also occur at a “higher frequency” with some diseases, such as scleroderma, portal hypertension, liver problems and people with HIV.

It can be difficult to diagnose because the shortness of breath is normally the first sign something is wrong.

“Having trouble walking with exertion, you are starting to develop shortness of breath,” she says. “Many different heart and lung disease can cause shortness of breath. Musculoskeletal disease can cause it.”

What’s more pulmonary arterial hypertension is rare, “a 25 per million disease,” and providers look for more common causes of shortness of breath, such as COPD, asthma, heart failure, McLaughlin says. Proper diagnosis remains important, and it is diagnosed after a right heart catheterization that measures the pressure in the lungs. There are several drugs available to treat it and most work by “relaxing the blood vessels” to reduce pressure, McLaughlin says. McLaughlin and her colleagues were involved in a clinical trial of a new potential medicine, Sotatercept, that reduces the number of cells that shouldn’t be there. Experts think that excessive cells in the arterial lung walls contribute to PAH.

“It’s what we call reverse remodel, getting rid of some of those overgrowing … blood vessels to help attack the actual problem,” McLaughlin says. “This medication is potentially reverse remodeling what has happened to the blood vessels in pulmonary arterial hypertension.”

For the trial, researchers looked at people on the standard of care treatment. Some received a placebo while others received the drug they were investigating. Participants did a six-minute hall walk before and after the trial to determine their ability.

“The six-minute hall walk is a very common endpoint in clinical trials in pulmonary hypertension,” she says.

They also measured clinical outcomes such as patients’ need for hospitalization, different therapies and quality of life.

“At the end of the 24 weeks in this trial, there was a statistically significant improvement in the six-minute hall walk, of about 40 meters, in patients who received the Sotatercept versus placebo,” she says. “There were also improvements in the first eight secondary endpoint so a really strong positive trials in almost everything.”

The researchers published the results in The New England Journal of Medicine. Currently, the medication is awaiting FDA approval before others can have access to it.

'Looking forward'

While Kauffman doesn’t know if she was taking the medication or the placebo during the trial, her health has improved (she's now officially on it because participants are all offered access to it following the end of the study). After first meeting with a transplant doctor in 2020, they planned on her coming back annually to see if she still needed a transplant — being in a clinical trial didn’t exclude her from it. But when she returned after being in the study, her outlook changed.

“When I went back for that next annual appointment we agreed that I was doing so much better that I no longer needed to come back,” she says. “It’s (been) put on hold.”

If she starts having more problems, they might reassess her need for new lungs. Kauffman also underwent genetic testing to see if she had genes for PAH because she worried that her younger sister and her children could be impacted by it.

“I don’t have any of the genes that they test for,” she says.

She feels grateful she had a chance to participate in a clinical trial for the condition.

“I just want to keep looking forward,” Kauffman says.

This article was originally published on TODAY.com