Woman had stillbirth in North Texas jail cell, says staff accused her of ‘crying wolf’

When Lauren Kent was arrested on a credit card abuse charge after she found a credit card on the ground and used it to buy a friend’s groceries, she assumed she would spend a few weeks in jail and accept the consequences the justice system gave her.

She did not expect one of those consequences to be the death of her unborn baby.

On May 29, 2019, Kent was taken to the Collin County Jail, where she waited for her pre-trial hearing because she could not afford bond.

Over the next 37 days, Kent, who was four months pregnant, begged for help from medical staff at the jail for her worsening abdominal cramping and vaginal bleeding, she said. She did not see a doctor the entire time she was in jail, and instead was told she could only receive off-site medical help if she saturated two full pads with blood.

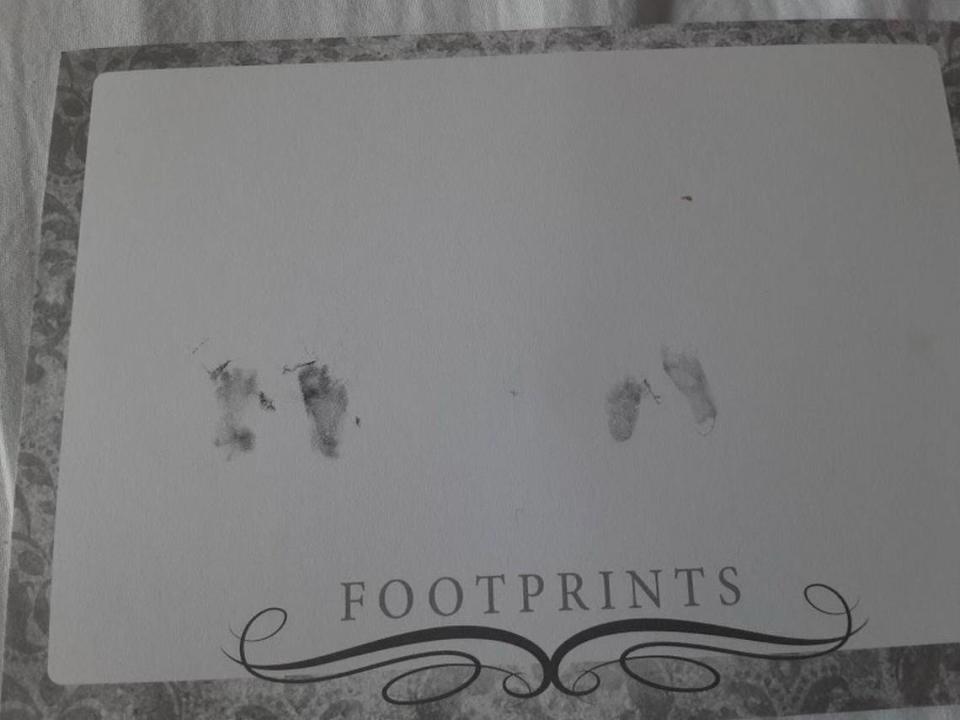

After being told she was “crying wolf” while in labor, Kent gave birth to her 4-and-a-half-month-old child in a cold jail cell over the toilet, she said. The baby, Dakota Lee, was dead.

Kent and her baby were the latest victims of a corporate medical provider that prioritizes saving money over people’s medical care, Kent and her attorneys allege in a lawsuit filed against the company and Collin County. The suit says Collin County officials were not only aware that their jail’s medical provider, Wellpath, saved money by neglecting inmates’ care, but specifically partnered with Wellpath because it promised to save Collin County money on inmates’ medical care.

On May 29, two years to the day after Kent was booked into Collin County Jail, she and her attorneys filed the lawsuit against Wellpath Inc., Collin County and four Collin County Sheriff’s Office employees who they say ignored Kent’s cries for help.

“It’s a horrible, tragic situation that was easily preventable,” attorney Scott Palmer said. “And they’re going to have to now answer for their inaction and be held accountable.”

In response to the suit, Wellpath told the Star-Telegram it could not comment on ongoing litigation.

“However, Wellpath disputes any characterization that it prioritizes cost saving measures over or to the exclusion of inmates’ medical care,” the statement said. “The health and wellbeing of our patients remain our top priority.”

Collin County officials said they contract with a third-party provider for all medical service provided in the county jail and they also denied the allegations made in the lawsuit.

Partnership with Wellpath

In 2015, Collin County was looking for a new medical provider for the jail.

Collin County’s top concern for a new provider was spending less money on medical care for people inside its jails, according to documents provided in the lawsuit.

“We are looking for good options to keep the inmates onsite rather than going to the hospital,” county officials wrote, according to the county’s response to a questionnaire from Wellpath. In the additional comments section of the questionnaire, a copy of which was included in the lawsuit, Collin County reiterated it “would like to minimize transport offsite.”

Wellpath assured Collin County this was a request it could meet. In fact, the company has a name for this exact cost-saving measure; the Cost Containment Program, Wellpath explained in a description of the program to Collin County, reduces the transport of people inside the jail to medical facilities by “optimizing the delivery of medical care onsite.” A person should only be taken to the hospital if they have a medical emergency that is a “life or limb threatening illness or injury,” according to a copy of this program policy that was included in the lawsuit.

This program saved another county an estimated $140,000 a year by reducing inmate transfers by 27%, the program description says.

Wellpath did not respond to requests from the Star-Telegram for a copy of this policy.

When considering its options of medical providers for inmates, Collin County wrote in a document, which was included in the lawsuit, that the criteria it gave the most weight to when choosing a new provider was cost. When described in percentages, the county said its decision about a medical care provider for inmates was 40% based on updated cost. The other two factors were projected staffing and how well the company answered questions.

Wellpath promised Collin County its Cost Containment Program would not compromise medical care for inmates — instead, the company said it would shift people’s medical care onto mid-level healthcare professionals at on-site clinics.

In August 2015, Collin County commissioners voted to partner with Wellpath, which at the time operated under the name Southwest Correctional Medical Group.

In 2018, the company now called Wellpath formed from a merger of smaller companies. A Wellpath administrator assured Collin County via email that the merged company would continue to deliver quality services for adult and juvenile healthcare.

But in 2019, a CNN investigation alleged Wellpath’s cost-cutting policies resulted in preventable deaths and serious injuries.

In lawsuits across the country, Wellpath, or one of the two smaller providers that merged into Wellpath in 2018, were accused of contributing to the deaths of 70 people from 2014 to 2018, CNN found.

By 2019, Wellpath was the nation’s largest for-profit provider of health care to correctional facilities, with contracts at more than 500 facilities in 34 states, according to CNN.

Wellpath disputed CNN’s findings. Wellpath officials told CNN that any unfortunate outcomes were isolated incidents that resulted from company policies not being followed.

Critics do not see the number of lives that Wellpath saves, Wellpath’s president told CNN, and all the people that the company helps in jails.

The company said that while certain agencies have raised concerns, most of its clients are satisfied. Employees, the company said, treat inmates as they would members of their own families.

In Kent’s lawsuit, attorneys Palmer and James Roberts laid out other cases of pregnant women receiving substandard care from county jails partnered with Wellpath. Six women filed suits after they gave birth on the floor of jail cells, saying staff ignored their cries for help. One woman, Shaye Bear, gave birth to a baby in an isolation cell at Ellis County Jail. The baby died nine days after he was born prematurely. Bear said she was moved to the isolation cell after her screams were ignored by staff who said she was faking a medical problem, WFAA-TV reported.

“The fact that this is happening in America, where counties are pinching pennies and being more cost conscious than care conscious, is really disturbing,” Palmer said. “And the fact that it’s happening in this area, in the metroplex is even more disturbing.”

‘I need a doctor’

As soon as she was booked into Collin County Jail in May 2019, Kent told a staff member she was pregnant. She thought she might be having twins, she told staff, and she already had a caseworker who was helping her through her pregnancy and possible adoption of the baby. A nurse employed by the Collin County Sheriff’s Office, Latori Abii, saw Kent on June 6 for a standard medical visit, and scheduled Kent to see her again in one month.

Kent made medical requests to staff through a computer kiosk, copies of which are included in the lawsuit.

On June 27, 2019, Kent started to have abdominal pain, cramping and vaginal bleeding. Through the jail kiosk, Kent sent increasingly desperate messages to staff about her worsening condition.

Medical staff told Kent to “keep a pad count.” This refers to Wellpath’s “24 hour pad count policy,” in which staff count how many menstrual pads someone saturates with blood in a day to gauge if they are bleeding the amount required to seek outside medical care.

On July 1, Kent sent another message, telling staff she had not felt her baby move for 24 hours and she passed a blood clot when using the bathroom.

In response, she received a message informing her she would receive the next available sick call, and would be charged $10.

On July 3, she saw Jelil Atiba, another nurse staffed by the jail. Atiba told Kent that she could not receive medical attention because she was not bleeding enough, according to the lawsuit. Another staff member, Julia McBride, told Kent via the message system that she needed to saturate two more pads with blood “within the next 30 minutes” to receive medical attention. She also noted that she could hear Kent yelling and crying in her cell.

“Per assessment, your issue is more behavioral than medical,” McBride wrote in her message to Kent. “Thanks and God bless, we are here to serve you.”

A staff member wrote two incident reports, which are included in the lawsuit, about Kent and her interactions with Atiba when the nurse saw her for her requested sick call on July 3. The staff member wrote that Kent was in tears and explained to Atiba that she had not felt her babies move in 24 to 36 hours.

“Nurse Jalil cut Kent’s explanation off with a raised voice,” the staff member wrote. “Nurse Jalil told Kent that if this behavior continued, she would be moved to the main jail and could not ever again return to minimum security. Nurse Jalil also told her that medical staff would determine if Kent went to the hospital.”

After this interaction with Atiba, according to the lawsuit, Kent sent a desperate message to staff; “PLEASE IM BEGGING YOU,” she wrote. “I NEED A DOCTOR.”

She then called the woman helping her with her baby’s adoption. The woman immediately called the Collin County Jail and asked for a supervisor. She spoke with a lieutenant, explaining that she was very concerned about Kent’s condition, the lawsuit says.

The lieutenant told the woman that, “you can’t believe everything that (inmates) tell you,” according to the suit.

The woman insisted that Kent receive medical care and, the night of July 3, Kent was taken to the infirmary at the jail.

Once there, according to hospital admission records included in the lawsuit, Kent was put into a cell and assessed by a nurse. She was told to keep a count of the menstrual pads she bled through.

Losing the baby

On July 4, 2019, 36 days after she was booked into Collin County Jail, Kent had her second appointment with the nurse she saw when she first arrived at the jail. The nurse, Abii, took a urine sample and diagnosed Kent with a urinary tract infection. According to the lawsuit, Abii told Kent that if “she was miscarrying, there was no magic pill she could give her to stop the process or reverse it.”

The next day, Kent went into labor. She told the nurses what was happening, the lawsuit says, but they did not believe her. After crying for help for six to eight hours, the nurse on duty, Michelle Pounders, told Kent that she was going to be moved to the main jail. In a phone call, she directed that Kent not be sent back to minimum security because she “would just continue to cry wolf,” the suit says.

“I felt it in my body that something was wrong,” Kent told the Star-Telegram. “When I felt I was in labor, I knew it was too early. I didn’t know I would be giving birth to my dead baby though.”

As she collected her belongings to move to maximum security, Kent suddenly rushed back into the cell.

“Kent delivered her child inside of a cold, filthy jail cell in extreme pain and fear,” the lawsuit says. “This situation is one of the most inhumane examples of deliberate indifference imaginable — but appears to be the practice and custom of (Wellpath) and Collin County.”

Kent delivered the stillborn baby over the toilet in her cell.

“It happened very quickly, in that last moment when he came out. It was very bloody,” Kent said. “And the nurse that had been saying, ‘you’re crying wolf,’ when she came in and saw it, she dropped to her knees and said, ‘I’m so sorry.’”

Another nurse took Kent’s dead baby from her and placed him in a red bag. Kent asked to hold the child, but the nurse refused, the lawsuit says.

Pounders called nurse Abii and told her Kent had possibly had a miscarriage. Abii instructed Pounders, according to a medical note included in the lawsuit, to have Kent continue to keep a pad count.

Kent was eventually taken to the hospital after her miscarriage. A friend bonded her out of jail for $125.

Hoping for change

Kent said she thinks about Dakota every day. She hopes by filing a lawsuit, changes will be made at Collin County Jail.

Her attorneys said they hope the suit also draws attention to a problem across North Texas.

“I don’t think that the public understands exactly the type of treatment that people receive inside Collin County Jail, or any other jail or prison,” Roberts said. “I think when people see that people are not being treated like people, they’re being treated like subhuman, that’s when we’ll see change.”

On March 14, the death of a man inside Collin County Jail made national news. Marvin Scott III died inside Collin County Jail after detention officers restrained him to a bed, pepper-sprayed him and covered his face with a spit mask, according to the New York Times. Scott was kept there for several hours and became unresponsive at some point. He was later pronounced dead at a hospital.

The medical examiner ruled the cause of death was “fatal acute stress response in an individual with previously diagnosed schizophrenia during restraint struggle with law enforcement.”

On April 28, the manner of Scott’s death was listed as homicide.

Collin County did not answer questions from the Star-Telegram about whether Abii, Atiba, Pounders and McBride — all listed as defendants in the lawsuit — still work with the sheriff’s department, whether an internal investigation was done into the death of Kent’s baby or why Collin County chose to partner with Wellpath.