Woman off the streets for three years afraid of becoming homeless again

ORMOND BEACH — Sandra Kissinger lives in a 60-year-old, 310-square-foot trailer in a no-frills mobile home park on the edge of U.S. Highway 1.

The rumbling traffic noise is nearly constant, and she has little privacy with neighboring trailers less than a stone's throw away.

But for her, in many ways, it's the best place she's ever lived. She's added artful, calming touches everywhere with seashell arrangements, plants, sky blue and seafoam-colored paint on the walls, and white lacy curtains.

Best of all she's the sole owner, and for almost the first time in her life, there's no one under her roof abusing her.

In a few months, though, she could be forced to leave and wind up back in the homeless shelter that helped her get back on her feet three years ago.

Her lot rent is going up $50 per month in May, and she doesn't know how she'll find that extra money.

Kissinger has a long list of health problems, and she's unable to hold down a job. She survives on $1,335 per month – just $16,020 per year – that she gets from Social Security Disability Income, Supplemental Security Income, food stamps and the CarePlus CareEssentials program.

Her current $569 monthly lot rental fee in the trailer park already devours nearly half of what she takes in, and the rest gets spent on essentials: power, cell phone service, Wi-Fi, over-the-counter medication, life insurance, toiletries, cleaning supplies and any groceries she needs after her food stamp funds are exhausted. There's also her therapist's $40 charge, clothes, shoes, and home improvement materials.

The storm finally passed: First Step Shelter helps homeless Volusia woman find peace, home

Possible new help for Daytona homeless: First Step Shelter working on a plan to create new on-site rental housing

Affordable housing coming to Midtown: After decades of sitting on the sidelines, Midtown seeing new home construction increase

As of March 23, she had $2.90 in her checking account, nothing in her savings account and $25 left on her CareEssentials card that she can use for food and other necessities.

Kissinger is trying to start a small business teaching people via Zoom meetings how she turns books into art, but she hasn't fully figured that out yet.

She's been paring expenses every way she can think of, including decreasing her use of electricity and cutting off service on a special phone that transcribes what people are saying as they talk to help with her hearing impairment. She thought about having a renter stay in her screened-in porch beside the trailer, but she doesn't want to chance being evicted if the tenant causes problems.

She's nervously wondering if she's going to have to sell the trailer she's spent three years fixing up with everything from new flooring to new paneling and try to find an apartment at a time local rents are as high as her entire monthly income.

"I'm trying and trying and trying, and I'm drowning," Kissinger said.

Orphaned as a toddler, abused as a child

Kissinger got a rough start in life, and she has spent most of her 55 years trying to regain her balance.

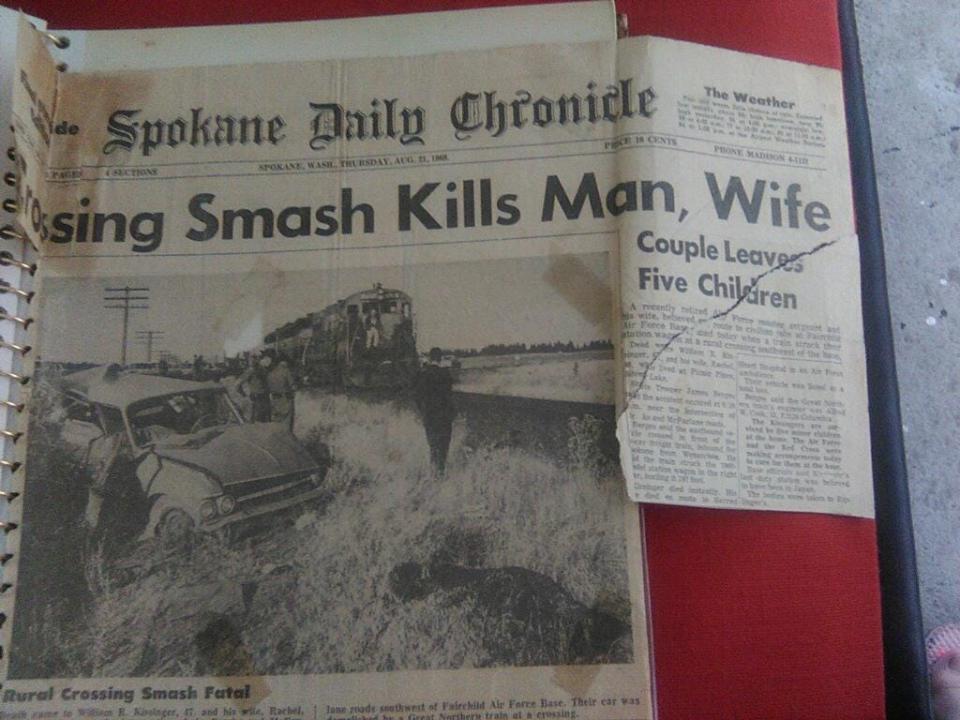

Just months after her family moved to Washington state in 1969, her life changed forever. One morning before the sun came up, her parents were driving through the darkness in a rural area they weren't familiar with.

As they crossed railroad tracks that weren't illuminated, a freight train slammed into their station wagon. They were both killed.

Kissinger was 2 years old, and she has no memory of her parents.

She was the youngest of nine children, and she and three of her siblings were sent to live with their father's sister in Ohio. Kissinger stayed in her aunt's home until she was 6 years old, and then she was shuffled around for the next 12 years. She lived with teachers, another aunt, and in three foster homes.

"Almost all of the homes consisted of some form of abuse during my stay, whether it was verbal, physical, emotional, psychological or sexual," she said.

She was raped when she was 11, and she has been in and out of therapy since.

Despite all the moves, she spent most of her childhood in the small town of Greenville, Ohio.

Another quarter-century of abuse, then freedom

She dreamed of being a model, but when she graduated from high school in 1986 she was being shifted out of the foster care system and she felt lost. Three months later, she wound up marrying a man she had met right after her senior year of high school.

The couple moved to Indiana and lived in a trailer while they built a house together on a large piece of land. Their property became a hog farm that Kissinger ran while her husband worked construction jobs.

They had three daughters together, and the girls became Kissinger's only joy in life. She said her husband was abusive, and she finally left him when she was 41.

She became a licensed practical nurse to support herself and her children, and that worked until she developed severe depression, fibromyalgia, debilitating migraines, anxiety and PTSD. She had to stop working and wound up filing for bankruptcy.

Not long after that, she married a second time, but she said that man also became abusive so she left less than a year into the marriage.

She moved to Florida with a boyfriend in 2017, and she was doing OK until that relationship ended in the fall of 2019. She had no place to live, so her sister let her stay with her. But that only lasted for six weeks, and on Dec. 15, 2019, Kissinger found herself homeless.

She had heard of Daytona Beach's First Step Shelter, which opened a few days after she became homeless. She was able to get in on Christmas Eve, a day she celebrates every year now by donating money to the shelter.

She was ready to live on her own by late March 2020, when she settled into her Ormond Beach trailer park home.

First Step Shelter Executive Director Victoria Fahlberg has kept in touch with Kissinger over the past three years, and has provided guidance.

"I'm just so happy about the way she's been able to manage for three years," Fahlberg said.

Kissinger has also come back to the shelter to volunteer and visit staff members.

"It always makes all of us at the shelter feel good when we can see the impact on her life, and that she's still grateful," Fahlberg said.

'Where else am I going to go, back to the homeless shelter?'

Fahlberg is aware of Kissinger's new rent struggle, and she's been trying to help her line up rent assistance since last summer.

Kissinger has also been trying to get into some sort of affordable or government-subsidized housing, but so far she's just finding years-long waiting lists. If there's a good option for her, she hasn't found it yet.

"Where else am I going to go, back to the homeless shelter?" Kissinger asked.

She would like to stay in the trailer for at least another year or two, but she's starting to think it's not going to be a good place to retire. Her health has taken some downward turns, and she won't always be able to make repairs and improvements to the mobile home.

Even now, physical work can leave her sore for days after. She doesn't have a car, and riding her bike to the grocery store is starting to cause so much back pain and leg weakness that she uses a cane and motorized cart once she gets there. Walking is also getting harder.

She said her hearing is getting worse even with hearing aids, she's having issues with pain medications and doctors are trying to figure out how to handle a partial blockage in an artery connected to one of her kidneys.

Her dream is to wind up in New Smyrna Beach on Canal Street or Flagler Avenue, a seaside thoroughfare lined with quaint boutiques, galleries, surf shops, restaurants, and other charming small businesses. She would love to have a little shop and live in an apartment above it.

She knows that's probably not where her life is headed. She would also be happy to live in the Windsor and Maley apartments in Daytona Beach, two high-rise buildings overlooking the Halifax River near the heart of downtown Beach Street. The low-rent apartments are for older people with health struggles.

She hates the thought of leaving the Ormond Beach trailer park. It's located just a few blocks west of the Halifax River, where she fishes, kayaks and hunts for seashells.

Her trailer is also just north of Granada Boulevard, so she's within a bike ride of many stores.

She likes the solitude and peace of living alone with her two cats, and the challenge of fixing up the trailer piece by piece. She's even added pavers and outdoor furniture to create an attractive front porch, and she's working on a back porch as well.

"I enjoy living on my own," she said. "I sew. I have adult coloring books, my two cats. I'm OK with this. Being by myself is so much better. Even though I'm struggling, it's my struggle."

You can reach Eileen at Eileen.Zaffiro@news-jrnl.com

This article originally appeared on The Daytona Beach News-Journal: Rising rent could make Ormond Beach woman homeless for a second time.