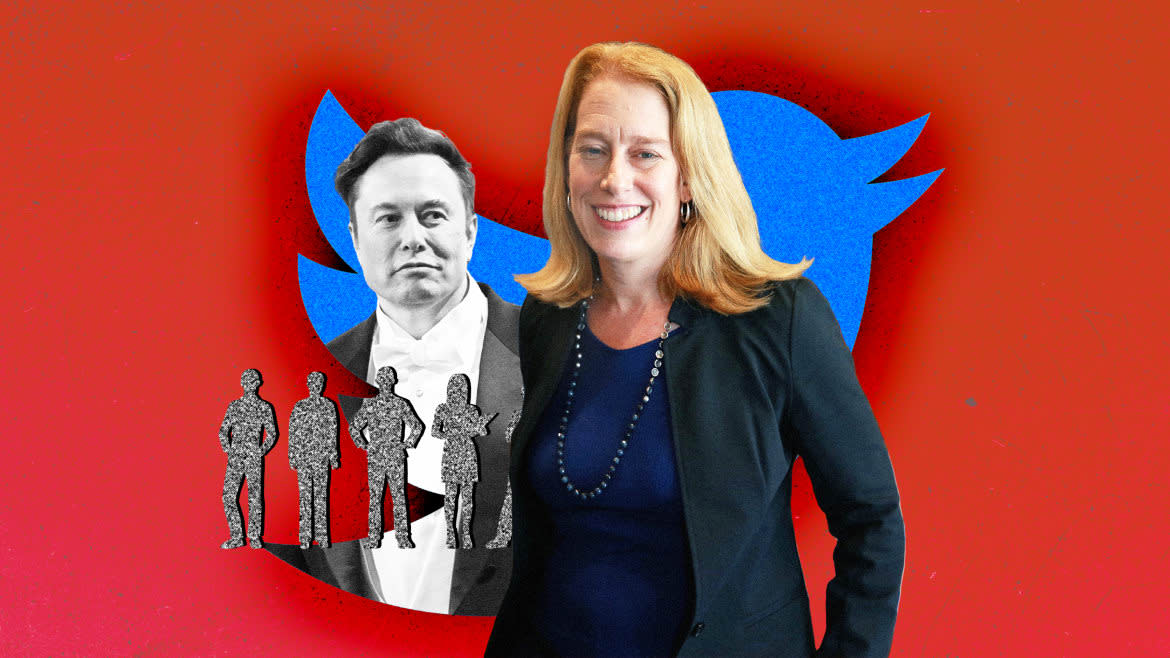

The Woman Who Plans to Make Elon Musk Pay for His Twitter Sins

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Earlier this year, as Elon Musk looked increasingly likely to lose his court battle and be forced into purchasing Twitter, Justine De Caires started to get nervous.

Like others, De Caires, a Twitter software engineer of three and a half years, predicted a Musk takeover would come with mass layoffs. Unlike many, the 25-year-old had closely followed the legal battle between the billionaire and the social media company and read every page of the merger agreement. “I get fascinated and interested in things very easily,” explained DeCaires, who uses they/them pronouns.

Twitter higher-ups promised to stick to a generous severance package in the event of a Musk takeover, De Caires says. But the engineer had doubts, and started looking for labor rights attorneys with a history of dealing with powerful tech companies. The first email was to a Massachusetts attorney named Shannon Liss-Riordan, who had filed a lawsuit against Tesla months earlier. The attorney called back that same day.

“It was kind of like, ‘OK, let’s wait and see how this goes,’” De Caires recalled of that first conversation. “But when things started happening—oh, she was ready.”

The mass layoffs at Twitter in November—a proverbial Red Wedding that cut the staff in half—has proven fertile ground for lawsuits. But Liss-Riordan, a labor rights veteran once dubbed “Sledgehammer Shannon,” was perhaps the best-equipped attorney in the country to handle the case. A chatty 53-year-old Boston transplant, Liss-Riordan has sued tech companies from Uber to DoorDash and won judgments of up to $100 million on behalf of their workers.

She has also attracted her share of critics: Opponents of her failed bid for Massachusetts attorney general pointed to the millions she earned from her signature class-action suits, suggesting she was more interested in money than the movement—charges she forcefully denies.

Today, the attorney has filed four lawsuits on behalf of laid-off Twitter employees, alleging transgressions ranging from disability discrimination to Title VII violations. Her plan, she says, is to convince the multi-billionaire that paying his laid-off employees would be easier than fighting them all in court.

“I find it really concerning when the richest man in the world—well, now the formerly richest man in the world—thinks that he can do whatever he wants and is above the law,” she told The Daily Beast.

“There needs to be a real deterrent to make sure that corporations [and] employers protect the rights of their employees and don’t think they can just get away with it,” she added. “It’s really important that our laws have teeth so that it’s not just like a traffic ticket for the richest man in the world.”

Shannon Liss-Riordan speaking to reporters about the United Steelworker's Boston Taxi Driver Association.

Before she was fighting Silicon Valley stalwarts, Liss-Riordan was advocating for waiters, bartenders, and bellhops in Massachusetts. As an ambitious 29-year-old fresh out of Harvard Law School and a federal clerkship in Texas, Liss-Riordan joined a small firm in Boston in hopes of “hanging out a shingle,” according to Harold Lichten, the partner who interviewed her for the job. “I thought that was just an amazing confidence,” Lichten recalled of their interview, which Liss-Riordan conducted from her honeymoon in Thailand. “Because you don’t just hang out a shingle in Boston.”

Liss-Riordan quickly became the firm’s resident expert in securing lost wages for tipped employees, using an obscure state law that prevented managers from dipping into the tip pool. In 2006, she secured an estimated $2.5 million in damages for wait staff at Hilltop Steakhouse in Saugus; two years later, she got American Airlines to pay nine local skycaps more than $325,000 in lost tips. (It was the skycaps who dubbed her “Sledgehammer Shannon.”)

Between 2001 and 2008, according to a Boston Globe analysis, she brought at least 40 lawsuits on behalf of tipped employees; in 2012, she won a $14.1 million settlement for Starbucks baristas. She estimates that over the course of her career she has won more than half a billion dollars for workers.

At the same time, Liss-Riordan became interested in workers who felt they had been misclassified as independent contractors instead of employees. Companies often use contractors to fill gaps in their full-time labor force, but Liss-Riordan felt many were overusing them to avoid paying benefits like health care and overtime. In the span of two years, Liss-Riordan sued on behalf of FedEx drivers, janitors, and even strippers who felt they’d been cheated out of employee status. Then she encountered her white whale: Uber.

Liss-Riordan interacted with company through drivers who felt it was taking their tips, but she instantly took issue with Uber’s entire business model—namely, creating an entire workforce of independent contractors. Shortly after filing the tip case for the drivers, she filed a class-action suit aimed at the heart of the company—and of many other “gig economy” platforms—arguing that its drivers should be classified as employees, not contractors. At the height of the litigation, the class consisted of 400,000 drivers in California and Massachusetts alone. She quickly followed up with suits against other gig economy standouts—Lyft, DoorDash, GrubHub, Postmates, and Instacart—and secured some sizable settlements. In 2019, she won $11 million for Instacart drivers who were not reimbursed for using their own vehicles; just last year, she scored $100 million for DoorDash workers.

Liss-Riordan listens to taxi drivers at Foley Square after over 5,600 sued the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission

But fighting the behemoths of the gig economy proved harder than clawing back tips for baristas. Drivers for Lyft and Uber remain classified as independent contractors and the underlying business model remains untouched. And because of the agreements many workers signed upon their hiring, her cases against both companies were eventually stripped of their class-action status and forced into private arbitration—a much more expensive, time-consuming, and ultimately less effective process. When she finally secured a $20 million settlement on behalf of Uber drivers, it was on behalf of about 13,500 drivers.

At the same time, the high-profile nature of her work started attracting critics. In 2016, after three years of fighting the case, Liss-Riordan believed she’d struck a $100 million deal with Uber on behalf of hundreds of thousands of drivers. But as sometimes happens in large class-actions, some drivers hired other lawyers to oppose the settlement, claiming it wasn’t large enough. The original lead plaintiff in the case, Douglas O’Connor, filed a motion opposing it, calling the agreement “disastrous” and claiming drivers had been “sold out and shortchanged by billions of dollars.” In an interview with NPR on the subject, Uber driver Adam Shaheen said: "The attorney Shannon doesn’t work for our side at all. We reject [that] she represents us at all.”

Liss-Riordan dismisses this backlash as a risk of the job, insisting that other lawyers often jump at the opportunity to contest hard-won settlements, hoping to grab a piece of the prize. She claims that only 30 of the 400,000 drivers ever complained about the deal. But after the drivers protested, the judge on the case actually threw out Liss-Riordan’s settlement, claiming it represented only 0.1 percent of the possible final verdict in the case. Liss-Riordan offered to lower her own fee by $10 million in hopes of saving the deal, to no avail. That same year, a judge in her case against Lyft also rejected her proposed settlement.

“I wonder if you’re now in a position of having to explain why a settlement of $12 million, 30 percent of which you propose to go to the lawyers, is a reasonable settlement, given the true maximum value of the lawsuit, which is somewhere in the neighborhood of $170 million,” U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria said at the time. (Liss-Riordan eventually convinced Lyft to settle for more than double the original amount.)

Earlier this year, during her run for Massachusetts attorney general, Liss-Riordan’s rivals rehashed these criticisms, painting her as a wealthy, out-of-touch lawyer who prioritized her own earnings over her working-class clients. Liss-Riordan, who lives in a five-bedroom, more than $4 million house and donated $9.3 million of her own money to her campaign, could “never truly be accountable to the people,” opponent Andrea Campbell said at the time. Just before the state primary, The Boston Globe ran an article with the headline: “Shannon Liss-Riordan Won Millions for Workers. But Did She Take Too Much for Herself in the Process?”

It’s a question that makes those who know Liss-Riordan bristle. “They criticized her for having money and made it seem like she didn’t earn the money,” said Steve Tolman, a 20-year railroad union representative who now runs the Massachuestts AFL-CIO, and who worked with Liss-Riordan on rideshare driver issues. “There was a campaign against Shannon… and I think it was essentially because she’s such a tough fighter.”

Liss-Riordan does not shy away from the topic of her own wealth—”I've done well in my fight against corporate America on behalf of workers,” she says—but says her fees are industry standard and none of her settlements have ever been overturned because her rate was too high. She said the millions she spent on her campaign was to boost her name recognition, and has argued it was better than taking corporate money.

Nicole Moore, the president of Rideshare Drivers United, a lobbying group that advocates for the interests of drivers in California, said it is difficult for her to get excited about lawyers like Liss-Riordan, who take a quarter of her constituents’ settlement checks in their cases. Her group prefers to work through the labor commission or the state attorney general’s office who, she said, will fight for their rights without taking “a bajillion dollars.”

Even so, Moore said, “there are so many lawyers out here—even Obama administration lawyers—who are on the wrong side of this stuff, working for Lyft and Uber.”

“[Liss-Riordan] was one of the ones who came out way early and said we’re going to fight for the drivers, not the companies,” Moore said. “If people are arguing we should get full protection of the labor law, I’m down with that.”

Elon Musk, shown here at a Halloween party, cleaned house immediately after buying Twitter.

Liss-Riordan’s first tangle with Musk was not with Twitter, but with Tesla. When the electric vehicle company laid off 10 percent of its workforce without written warning earlier this year—a violation of the federal WARN Act, Liss-Riordan argues—she sued on behalf of two terminated workers, seeking class-action status. Soon after, according to a protective motion she filed, Tesla offered two-week severance packages to anyone who would sign away their rights to sue. Liss-Riordan convinced the court to make Tesla inform anyone signing a severance package of the suit, but the case hit a familiar roadblock: Due to agreements the employees signed when they first joined Tesla, a judge refused them class-action status and sent the case to individual arbitration.

The case did have a silver lining: When De Caires went to look up lawyers in late October, Liss-Riordan was the one of the first to pop up.

“I was like, ‘OK, she’s worked with Elon before, maybe this is right up her alley,” De Caires recalled. “It seemed like I should get in touch with the one person with the requisite experience.”

In the following days, De Caires kept Liss-Riordan updated on goings-on at Twitter, and the two brainstormed about who would make a good addition to the suit. By Nov. 3, the day before Twitter was set to enact the mass layoffs, Liss-Riordan had signed up enough laid-off employees for a complaint. She was planning on filing the next morning—until workers from around the country began sending her panicked messages that they’d been locked out of their accounts. By the time De Caires texted her to say they were also locked out, Liss-Riordan was prepared. She filed her first suit against Twitter at 1 a.m..

Liss-Riordan’s first suit is similar to the complaint against Tesla in that it claims Twitter violated the WARN Act by failing to give 60 days notice of the layoffs to some employees, and failed to uphold severance agreements with others. But she didn’t stop there. Two weeks later, Liss-Riordan filed a similar suit on behalf of contractors hired through a third party. Then she heard from Dmitry Borodaenko, an engineering manager and cancer survivor who says he was laid off after telling his manager he could not return to the office under Musk’s new mandate because he was immunocompromised. Liss-Riordan quickly filed a suit alleging disability discrimination on behalf of Borodaenko and other similarly situated employees, which was later expanded to include anyone laid off while on medical or parental leave.

Along the way, Liss-Riordan obtained access to a spreadsheet detailing which of Twitter’s 7,000 workers had been laid off and asked a statistician to analyze it by gender. The result: 57 percent of women at the company had been laid off, compared to 47 percent of men—a discrepancy that could have occurred by chance less than 10 in 100 trillion times, according to the complaint. Musk’s defenders argue that he prioritized preserving engineering jobs, which skew male, but the complaint says the gap continues within the engineering workforce, with 63 percent of women laid off compared to 48 percent of men.

On Dec. 7, Liss-Riordan filed her fourth lawsuit against Twitter, alleging gender discrimination in violation of Title VII.

“I have a family, I have a kid to support,” one of the plaintiffs, Wren Turkal, said at the press conference. “All that we’re looking for is fairness.”

Twitter is pushing back forcefully, but Liss-Riordan learned a few tricks from her tango with Tesla. Immediately after filing the first suit, she asked the judge to block Twitter from asking laid-off employees to sign away their right to sue without first informing them of that case. Much like in the Tesla case, the judge sided with her. Earlier this week, after Tesla failed to move the case to arbitration, Liss-Riordan filed 100 individual arbitration demands in an attempt to call their bluff.

“If Elon Musk wants to fight these claims one by one in individual arbitration, we are ready to fight them one by one, on behalf of potentially thousands of employees if that becomes necessary,” she said in a press release. “We have done it before and we are ready to do it again.”

It was a strategy she'd pioneered 15 years earlier while fighting an early gig economy company that classified its cleaning staff as independent contractors.

“Usually the company is like, ‘Wait, we just thought you’d all go away,’” she said with a smile. “And we’re like, ‘Sorry, you asked for it.’”

Liss-Riordan is far from the only attorney getting in on the Twitter layoff gold rush. Lisa Bloom, an attorney as famous for her work on sexual harassment cases as she is for her early support of Harvey Weinstein, entered the arena on Dec. 5 with arbitration claims on behalf of three employees. New York attorney Akiva Cohen threatened a similar arbitration campaign at the beginning of this month. De Caires said there is a Slack channel filled with hundreds of laid-off Twitter workers debating the best attorneys to hire or suits to join.

But De Caires is satisfied with their choice. The engineer has read everything on the docket for the case, and often asks Liss-Riordan, “‘I saw this thing in something that Twitter filed, what do you expect is going to happen next?’”

“She tells me what she expects, and a few days later, exactly that happens,” De Caires said. “I feel very good that I chose Shannon.”

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.