A woman was raped on a Philadelphia train and witnesses did nothing. Why?

On May 26, 2017, Rick Best, a technician for the city of Portland, Oregon, was heading home on a commuter train when a man began shouting racist and anti-Muslim slurs at two teenage girls – one Black and one wearing a hijab. Best and two other men did exactly the right thing: They confronted the attacker and told him to stop harassing these girls. The attacker then pulled out a knife and stabbed all three, killing Best and one of the other men.

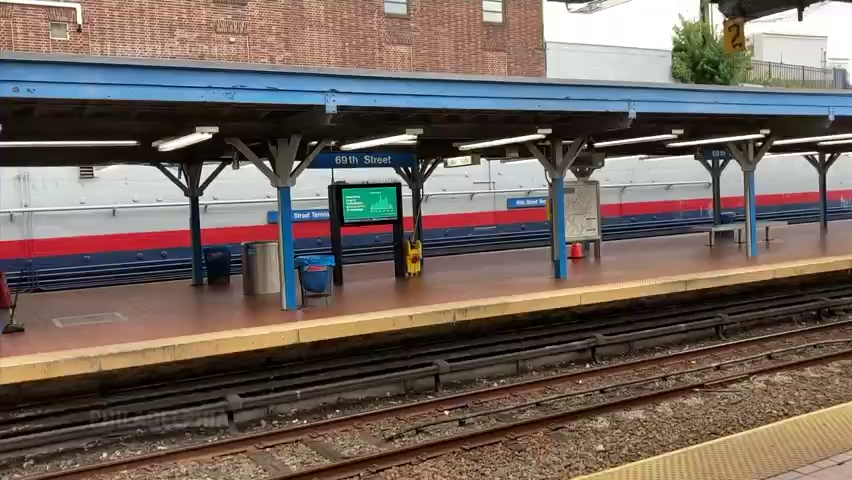

This story came immediately to mind when I read the horrific accounts of a rape occurring on a train near Philadelphia last week, when numerous riders watched and did nothing. They didn't even call 911.

Most of us like to think of ourselves as good people, who would surely step up in the face of bad behavior. Yet research in social psychology sadly reveals that most people – like those on the train – in reality will not.

How do we explain their inaction?

No one wants to overreact

First, they have to figure out what’s going on – and this can be complicated. Social psychologists have consistently found that people are far more willing to take action in the case of a clear emergency than when they find themselves in an ambiguous situation. Inaction in ambiguous situations is driven by what psychologists call evaluation apprehension, a term used to describe anxiety caused by fear our behavior will be judged by others.

Evaluation apprehension helps explain why only 19% of people intervene when they see a fight between a man and a woman when they believe they are watching a romantic quarrel – because the woman yells out “I never should have married you” – whereas 65% of people intervene when they believe they are watching a fight between strangers – when the woman yells out “I don’t know you.”

Stopping the next George Floyd killing: Empowering bystanders, encouraging ethical police

What’s the difference? Intervening in a potentially violent conflict between strangers seems like the right thing to do. But interfering in a domestic dispute may just cause awkwardness and embarrassment for all parties. Perhaps some riders on the train outside Philadelphia failed to intervene because they assumed the sexual assault was between romantic partners instead of strangers.

When facing an ambiguous situation, our natural tendency is to look to others to figure out what’s going on. But here’s the problem: If each person is looking to the people around them to figure out what to do, and no one wants to be seen as the person who overreacts (risking feeling foolish and embarrassed), the person in need might receive no help at all. In other words, inaction breeds inaction.

Your neighborhood matters

There’s another factor that may well explain what happened on that train car. Even in an obvious emergency, it can be hard to intervene if we think that doing so could pose a significant or even life-threatening risk to us. Before deciding to act, most people conduct a subconscious cost-benefit analysis. If the benefits outweigh the costs, we help. But if the costs outweigh the benefits, we don’t.

And one factor that consistently influences these costs-benefit calculations is geographical location. One study of more than 14,000 people who experienced cardiac arrest in 29 cities found that CPR was delivered 50% less often in low-income, predominantly Black neighborhoods than in wealthier, predominantly white neighborhoods.

Author Lois Lowry: Texas Holocaust book debate should teach us to stand up and say 'No'

Although this finding suggests that people in affluent neighborhoods are more likely to give help, it could be because more of them have training in CPR. To test the possible effect of training, researchers at Cornell University examined all types of bystander help in over 22,000 medical emergencies in neighborhoods across America. Many of the helping activities – offering water, covering someone with a blanket, providing a cold compress – required no special skill. The researchers noted each neighborhood’s socioeconomic status (based on median household income, education level and rate of poverty) and density (based on number of people living in a square mile).

Opinions in your inbox: Get a digest of our takes on current events every day

How did neighborhood influence helping? People living in high-density areas were less likely to get help than those living in less crowded environments. But neighborhood affluence had an even greater effect than density: People living in poor areas were significantly less likely to get help.

Research in sociology suggests that in neighborhoods with few resources and high levels of disorder and crime, people tend to develop a general sense of mistrust and to believe that others are more likely to hurt than to help them. Greater mistrust means that the cost of helping seems higher, and so bystanders are less willing to step up and act in an emergency. It’s therefore not surprising that the Market-Frankford Line on which last week’s rape occurred has been identified as one with high levels of disorder, and described by the city’s transit workers’ union as overtaken by the homeless, drug users and dealers.

But bystander inaction is not in fact inevitable: Some people do step up, even when the stakes are high. Ted Huston and his colleagues interviewed people who had intervened in a dangerous situation – a mugging, robbery or bank holdup – and compared them with those who hadn’t intervened. Those who stepped up were far more likely to have received training in some type of lifesaving skills, such as first aid. In fact, 63% of those who intervened had received such training. They weren’t different in personality – but they were equipped with different skills.

Why does training make such a difference? Training increases bystanders’ feelings of responsibility to act as well as confidence that they can do so effectively. Knowing what to do and how to do it is a good start.

Catherine A. Sanderson is the Poler Family Professor and chair of Psychology at Amherst College and the author of "Why We Act: Turning Bystanders Into Moral Rebels."

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Philadelphia train rape: Witnesses didn't step in, but there's hope