Women fighting harder than ever to break through the male-dominated sporting narrative

At last weekend’s Australian Open final, Naomi Osaka’s victory over Jennifer Brady in straight sets left some fans wanting more. The debate reignited the conversation around whether women should play five sets in tennis as Andy Murray put the question to his 1.7 million followers.

Yet as far back as the late 1990s, the likes of Steffi Graf and Martina Hingis were among those who had disproved the myth that women are incapable of playing five sets.

In 1984 the Women’s Tennis Association had decided to introduce five-set finals at their end-of-season event, and six years later the tour witnessed its first match go the distance. A 16-year-old Monica Seles, just two months after becoming the youngest French Open champion, tussled with Argentina’s Gabriela Sabatini before winning after nearly four hours. Afterwards, she smiled and said she had “enjoyed every minute” on the court.

The longer format remained for 14 years, producing three five-setters in that time, and acts as a reminder that female tennis players have the stamina to sustain the fight.

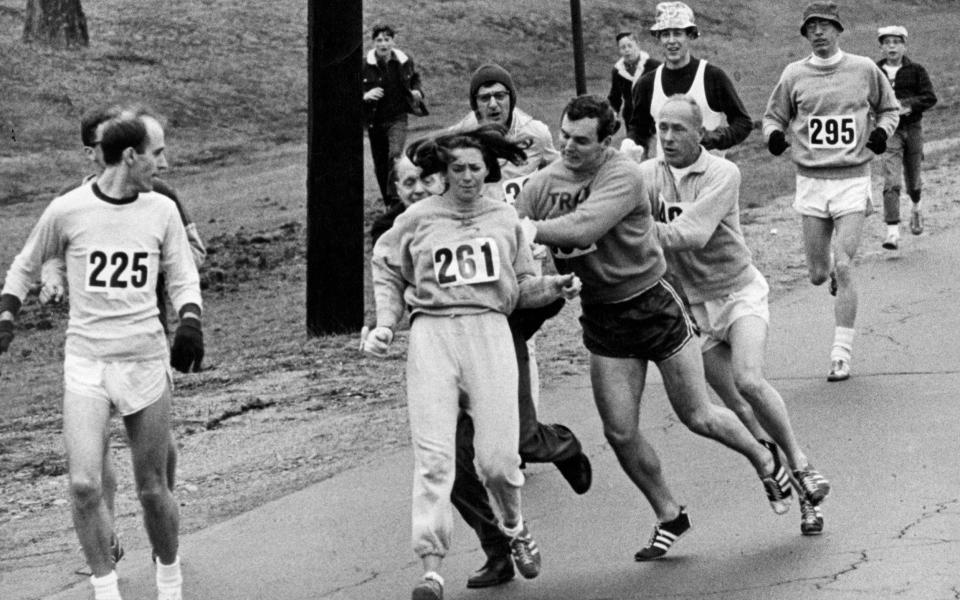

Elsewhere, the myth of men’s unequivocal physical superiority has been debunked by female athletes, too. Kathrine Switzer was the first registered female runner to complete the Boston Marathon in 1967, but had to wrestle away from race organisers clinging to her vest during the race, such were their doubts about a woman’s ability to finish the distance safely.

We have come a long way since, and now women are not only entering ultra-endurance competitions, but clocking faster times and winning races against men – despite making up a tiny proportion of the participants. Ann Trason was a pioneer, holding the title of ultrarunner of the year for more than a decade during the Eighties and Nineties in a field dominated by men, and led the way for other women in ultra-sport.

Britain’s Jasmin Paris is one of those following her legacy. In January 2019, she became the first woman to win the 268-mile Montane Spine Race. In her first attempt at the event she smashed the course record by 12 hours, nailing a maiden victory in 83hr 12min 23sec.

“The Spine was in midwinter, a lot of it was in the dark, you had to navigate, feed yourself, get the right amount of sleep whilst remaining competitive,” Paris says. “It’s hugely mental and that’s why I think the difference between men and women disappears.”

She does not consider herself a myth-debunker, though – “When I’m running a race, I just race it” – but understood the impact of her feat before she had even reached the finish line. At the final checkpoint, as dawn was breaking on the last day, volunteers told her about the buzz she had created on social media: “That was inspiring for me. I felt like I was in a privileged position, to be used as a role model for women’s achievement in sport.”

That Paris was expressing milk for her one year-old daughter during the race also rubbishes long-held beliefs that a woman’s career in sport would spiral downward after having children. This issue has been given more prominence in sports coverage in recent times, helped in no small part by Serena Williams, the most high-profile sporting mother of all since 2017. Her tennis rivals Kim Clijsters and Victoria Azarenka led the charge too, while Jamaican sprinter Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce’s world-title victory lap with her son on her hip in 2019 sent the message that not only are mothers capable – they can thrive at the top of sport.

These myths extend beyond the limitations put on what women can physically achieve. Merely occupying certain spaces in sport can be contentious, namely coaching. A Telegraph Sport exposé this month found that women athletics coaches had been routinely sidelined at elite level, while a rumbling debate ensued when Emma Hayes was linked to the AFC Wimbledon managerial job, as no woman has ever coached in men’s elite football in England.

Tennis is ahead on this front, but only marginally. Double major champion Amelie Mauresmo coached Andy Murray for two years and then top-10 player Lucas Pouille up until October. But she was the only woman coaching in the top 100 of the Association of Tennis Professionals tour, and came under intense scrutiny when coaching Murray, to an extreme he says was never the case for his male coaches.

It is a lesson that, unfortunately, Cherie Pridham will be primed for as directeur sportif of Israel Start-Up Nation this season, becoming the first woman to lead a men’s WorldTour cycling team. To break through the glass ceiling is not the only challenge. A higher standard awaits when you get there. “For me, I want to get it right,” Pridham said upon her unveiling in December, in a subtle acknowledgement of that fact, “because when I do, I know that it will inspire others to take the same journey and that really does mean something to me.”

One woman’s achievements can inspire an entire generation, but failure can also – unfairly – lock successive candidates out. In motorsport, only two women have ever qualified to race in a Formula One championship, and the last woman given the opportunity to try – Giovanna Amati – was dropped by her Brabham team after falling short of qualification on three occasions in 1992. Three decades on, the breakthrough feels closer than ever, with Williams development driver and W Series champion Jamie Chadwick the front-runner. But there will be extreme pressure on the woman given the keys to the ignition – succeed or risk another 30-year wait.

Still, historic moments and breakthroughs must be celebrated. Tennis player Fran Jones is testament to that. At the Australian Open she made her major debut, capturing worldwide audiences. With a rare genetic condition, Ectrodactyly Ectodermal Dysplasia (EED), she was born with a thumb and three fingers on each hand and seven toes, and as a child was told by a doctor that her tennis dreams could never be realised. But the 20-year-old qualified for her first grand slam on her debut attempt, already has WTA wins under her belt, has the backing of an LTA pro scholarship, and is within reach of breaking into the top 200.

“I would love other people to tell themselves what their limits are, not being limited by others,” Jones says. “Everyone that may find themselves in a similar position, dealt a different set of cards, they just need to find a way to use those cards to keep pushing them forward.” She has busted the myth that physical difference should prevent her playing on an equal platform with her competitors.

Tennis is renowned as the sport that most embodies progress for women. And yet, despite vocal support from the likes of Serena and Venus Williams to play five sets, organisers continue to choose not to have women competing in the same format as men.

In that strange way, five-set tennis stands as both a symbol of how myths in women’s sport can be busted, but also of how they are too quickly eroded. Women are still having to work harder than ever to break through the pervasive, male-dominated sporting narrative.