The women who provided abortions before Roe give a 'grim' glimpse of life after it

In the late 1960s, when abortion was still illegal in most of the country, a group of politically engaged young women in Chicago took matters into their own hands and formed an underground network to help people obtain safe and affordable abortions.

The solution for anyone in need was to call “Jane," the code name used by the coalition of mostly white, middle-class women who defied the law by facilitating an estimated 11,000-plus abortions between 1969 and 1973, when Roe vs. Wade made abortion legal.

At a perilous moment for reproductive rights, “The Janes,” a documentary premiering Wednesday on HBO, revisits the work of what was then called simply "the service” but has more recently been dubbed “The Jane Collective.” (The formal name was the Abortion Counseling Service of the Chicago Women's Liberation Union.)

Featuring first-person accounts from more than a dozen women involved with the service, “The Janes” offers a powerful look at an era before abortion was widely available and when most options for terminating a pregnancy were dangerous and unreliable. There are harrowing recollections of abortions performed by ruthless mobsters, doctors who expected sexual favors of their patients, and desperate women who died alone in Chicago’s septic abortion ward.

But the story is also told with surprising humor and spy-movie intrigue; we learn how the women, trained to drive to avoid being followed, shuttled patients from “the front” (the waiting room) to “the place" (the treatment room). We meet colorful, only-in-Chicago characters including the gentle and compassionate man, known only as “Mike,” who provided abortions for the service — and turned out not to be a doctor but a construction worker. And most of all, we get to know "the Janes," who juggled their clandestine activism with motherhood, marriage and academia.

“These are incredible women, full of life. It was important to capture that,” said Emma Pildes, who directed the film with Tia Lessin. “But the reality of what this country — what any country — looks like when women don't have a right to basic healthcare and bodily autonomy is so grim and so grave.”

In the coming days, the Supreme Court is expected to rule in Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Based on a draft majority opinion leaked last month, the court appears poised to strike down the Roe vs. Wade decision after 50 years, a move that would likely lead to abortion bans in at least 26 states.

Lessin and Pildes say the shifting political winds in the country inspired them to make “The Janes,” which they were working on as Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett were appointed to the Supreme Court, dramatically shifting the outlook for abortion rights.

“We were racing the clock to get it finished before Roe was overturned. The threat of that decision loomed over us making the film and I think it loomed over the women of the Janes as they agreed to talk to us,” said Lessin. “They understood the urgency of the moment.”

“I think it was about a second call to duty,” added Pildes. "They made themselves useful in this fight, laid it all on the line in the ‘60s and ‘70s. And here they are, again, feeling like there's something that they can do to help.”

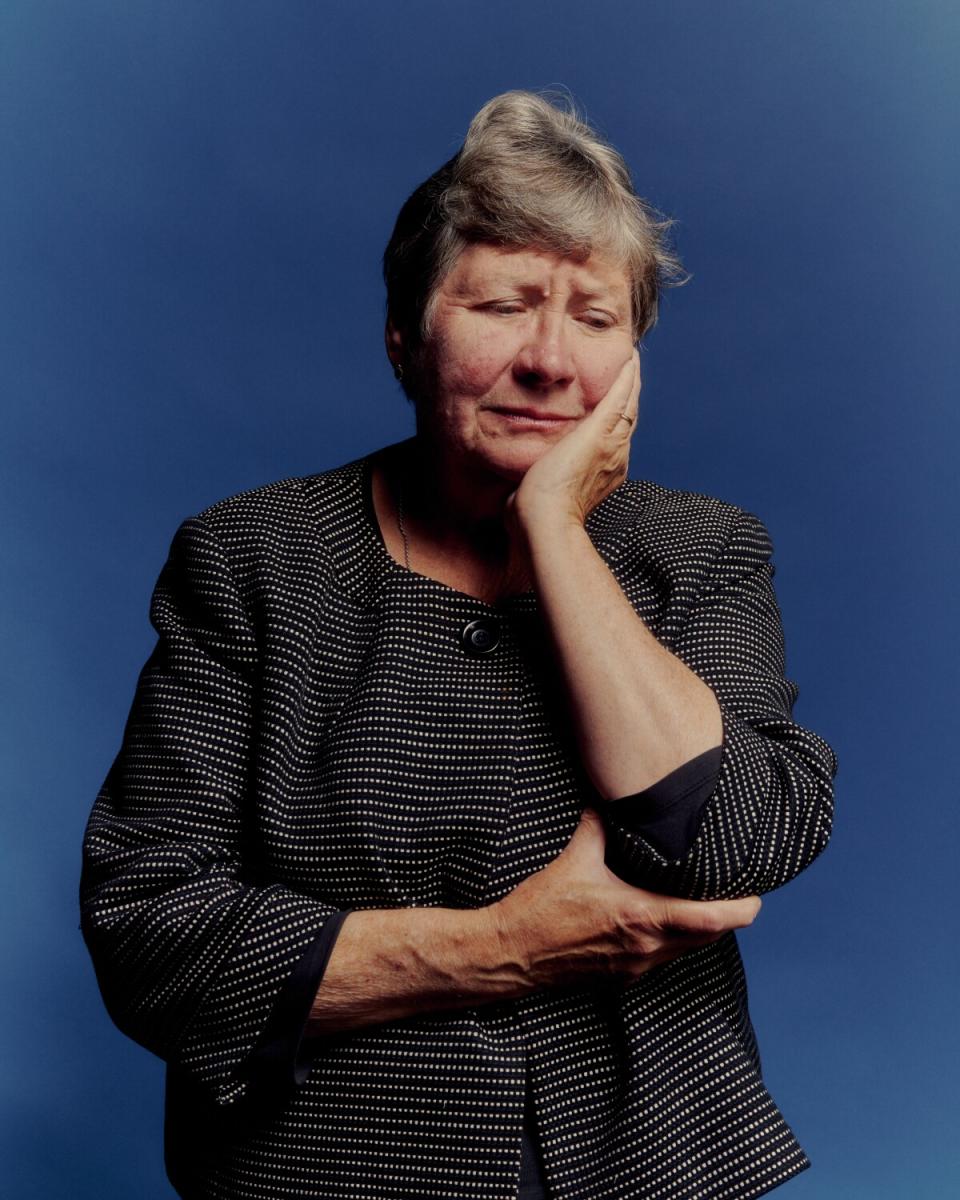

The Times recently convened four of these women, who are now in their 70s and continued to work in politics and advocacy after their time with the service. They are: Laura Kaplan, activist and author of "The Story of Jane: The Legendary Underground Feminist Abortion Service”; Heather Booth, a civil rights activist who made the first referral for what became the service and is a longtime Democratic organizer and advisor; Abby Pariser, a veteran reproductive rights advocate; and Sheila Avruch, who is now retired from the Government Accountability Office, where she worked on maternal and child health.

What has it been like to regroup after so many years, especially given the state of abortion rights in this country?

Avruch: It has been a very, very emotional experience. In D.C., one woman said her grandmother had died from a botched abortion when her mother was a small child and it affected her mother her whole life. She thanked us for what we had done. I also found out that amongst my group of friends at the University of Chicago, a number of people had quietly been helping Jane by lending apartments and cars. So that deepens my friendship with them too.

Booth: These are difficult times. It's also inspiring. Not only are people telling stories that are moving and emotional, people are saying, “OK, I stopped being active, I'm going to be active now. I realize we can do something, we need to do something.”

Did the people in your lives know about your work with the service?

Booth: I don't recall discussing Jane with anyone beyond my most intimate, closest relations or people who were in Jane, [until Kaplan reached out while writing her book]. I was not sure about the statute of limitations.

Pariser: Because we were in Jane and we talked about placentas and vaginas and cervixes, we became inured to the shame part of it. Walking into Woolworths and buying five cases of super Kotex at once — I didn't think anything of it. I talked about it all the time. When people say, “What were you doing in Chicago?” I would tell them.

Avruch: I was very proud of having been in Jane, but for a long time, I didn't talk about it much. I was working in the government in a buttoned-up agency and I was working with a lot of Republican staff. Even really close friends of mine, I never told them about it. Because I've never seen a moment to say, “Oh, by the way, I was arrested.”

I was struck by how this documentary counters many of the depictions of abortion we see in movies and TV. From your perspective, how has pop culture done in its portrayal of abortion?

Kaplan: In the film “Juno,” [the protagonist] goes to a clinic where the people are just completely uncaring and cold. I'm sure that happens at some clinics, but that's one of those tropes that we need to get rid of. “Never Rarely Sometimes Always,” about the young girl from Pennsylvania who goes to New York — that depiction was really spot on.

Pariser: If any of you have seen the French film called “The Happening,” it shows a [young woman] who wants to go to university and she's pregnant, so she goes to the neighborhood catheter lady. And then this young woman almost dies. It's so not pretty, but it's so real.

Booth: There were things captured in this documentary that are just extraordinary. They got Mike on camera, saying things like, “Well, I never said I was a doctor.” “But what did they call you?” “Dr. Kaplan.” [laughs]

I've always thought the true story is more dramatic than a fictional one. And [the film] gave more of a sense of the sisterhood that was created. Each woman in it, I think to a person, is so warm, funny, real. It humanized us in ways that were honest and true.

Avruch: One of the things that films [often get wrong] is that an awful lot of women who are getting abortions already have several children. They have only so many resources, and they need to focus on the children that they have. My experience with the service was I mostly counseled women who had children.

Have you thought about what you will do if Roe vs. Wade is overturned, as is widely expected?

Kaplan: Radical action is a young person's game. Heather started doing this at 19. We were in our 20s. We were kids, really. But I think what Jane provides is that sense that you are not helpless or hopeless. We all have the ability to do what we can, right now, that makes a difference in people's lives. There's a lot of young activism around the country that's just unbelievable. They don't need us to train them to do anything. I always say, we were ordinary people who accomplished something extraordinary.

Avruch: I did a panel at the University of Chicago, and there were eight women, medical students, all of whom were committed to learning abortion techniques. Their enthusiasm was really heartwarming to me.

One of the most powerful images in the film is the index cards on which you wrote down information about each of the women who called the service for counseling. Each one of them tells a story. Is there a story that has stayed with you — a woman you think about?

Pariser: I think about this 52- or 53-year-old woman who came to us pregnant, because her gynecologist said, “Oh, no, no, you're so old. You're going through the change. You’re not going to get pregnant." And then when she was pregnant said, “Oh, sorry.” Like, thanks.

Avruch: I remember a young woman who was from Mayor Daley's neighborhood. She couldn't tell her family. She and I ended up being on the phone a number of times after [the abortion], because she could only talk to me about it. But at some point, she told her mother and her mother was really supportive rather than being negative. And it meant so much to her.

Booth: One of the last women that I counseled came back after the procedure with her boyfriend and a bottle of champagne and flowers, saying, “Someday I hope I'm able to have the happy family that you have, but I'm not ready now.” The women who came through, in my experience, were uniformly grateful, appreciative for both having this procedure done but also for being treated with care and respect, which some of them had not been used to — not only in their medical care, but in all society at those times.

Some of you were arrested in a 1972 raid by Chicago police. That must have been terrifying.

Avruch: I thought very hard and deep before I joined the service, because I thought there was a good chance that either I might be arrested or that someone might really get hurt who came through the service. I think most of the people in the group didn't think they were gonna get caught. But for some reason, [having] a somewhat pessimistic point of view, I thought it was possible. So I wasn't surprised. I just saw my future crumble away. I was about to graduate from college, it was a turning point in my life, and I was really, really frightened. Especially when we were in the lockup — that was a scary, scary place. You could hear people screaming all night.

Pariser: I think knowing that what we were doing was illegal and was a crime was a very small part of our daily lives. Sure, we knew. I mean, why else do we have "the front” and “the place”? We weren't saying, "Oh, come here, do it right here on the couch.” But the chutzpah of renting an apartment and having a permanent place was really too much.

Kaplan: The bottom line is, the majority of us were white, middle-class girls, young women, who didn't believe anything bad was ever going to happen to us. Because we were privileged. We all knew the possibility was there. But there was this piece on top of that that came from our position in the world. It was a very different story for women of color who joined the group. They didn't have any of that bolstering.

What all did you take from this experience?

Kaplan: It completely changed my life. I don't think I even bothered to balance my checkbook before this. And here I was, taking responsibility for other people's lives. It changed the way I thought about myself and put me on a path. I’ve basically been a community organizer ever since. So I'm grateful to my friend Alice’s badly inserted IUD.

Avruch: It’s amazing what a group of organized women can do. Many of us developed strong bonds, and that was really important to making it effective.

Booth: Well, there's so many lessons about the injustices across race, as well as gender and class — about what it means to have real sisterhood. There are two big lessons that I share almost all the time. We need to organize. And we need to take action. But we need to do it with love at the center.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.