Women & Sport: This Teaneck tennis icon opened the doors for future Serenas

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

During the first week of the U.S. Open, all eyes have been on Serena Williams, one of the greatest athletes of all time who will say goodbye to tennis after the Open concludes. It’s been a historic run for a historic athlete.

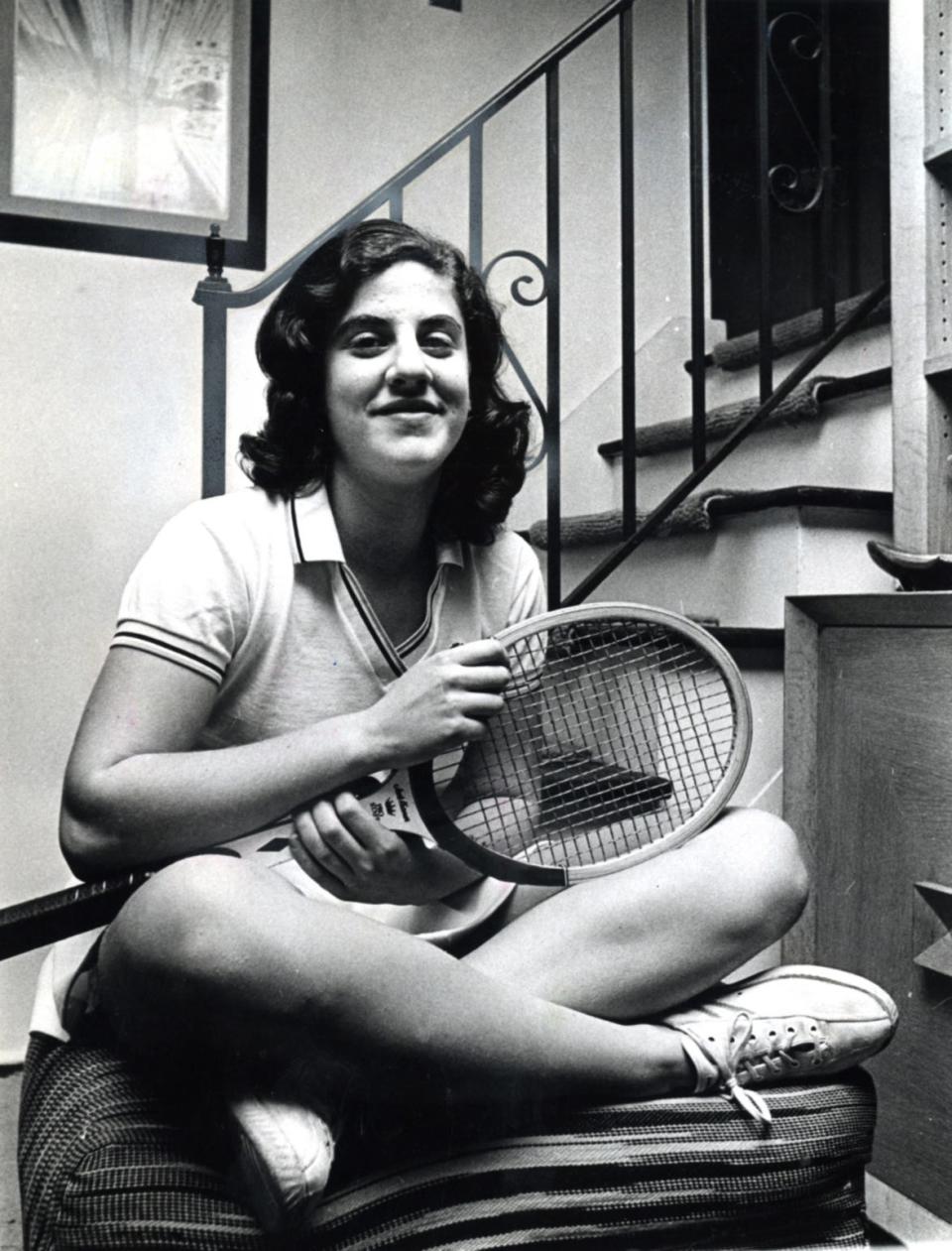

But before Williams, there were others who cracked tennis doors open so the next generation could barrel through. There was, for instance, Abbe Seldin, a nationally ranked tennis player from Teaneck in the 1970s who sued local officials for her right to play tennis with the boys.

Seldin, like Williams, transcends tennis — largely for taking the first step towards leveling the playing field for girls in high school in the months leading to the passing of Title IX.

Seldin’s story is one that shouldn’t be forgotten. Her fight to play tennis is often remembered as a legal footnote in the decorated career of another pioneer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The justice happened to be Seldin’s attorney when she sued Teaneck officials for her right to play.

It all started in 1972, when Seldin was 15 years old and a sophomore at Teaneck High School. The teen wanted to play tennis, but the school did not have a girls’ team. When she asked to play with the boys, school officials refused.

At the time, the New Jersey State Interscholastic Athletic Association prohibited females from participating with male athletes, even in non-contact sports. When asked why, NJSIAA officials pointed to “substantial practical, psychological and physical reasons for separating girls and boys on the high school level in competitive sports and in tennis in particular.”

They also cited the emotional implications of boys competing with girls in head-to-head matchups – and the chaos that would ensue if a girl suffered a leg cramp and there were no women around to treat her injury. Yes, really.

Women & Sport:As female stars retire, they pivot to improving women's sports off court

Seldin wasn’t concerned about proving those gross falsehoods wrong, though. All she wanted to do was play tennis. So she and her mother, Shirley, approached the ACLU in Newark for help. They were put in touch with Ginsburg — then a well-regarded Rutgers law professor on the verge of transferring to Columbia Law School faculty. Ginsburg wanted more courtroom experience, so she volunteered with the ACLU’s New Jersey chapter. She took the case — along with another notable attorney and Rutgers professor, Annamay Sheppard.

The case received considerable attention from the local press and spurred a conversation about inclusion in sports. The case was eventually dropped after the state agreed to change its rules and allow girls to try out for boys’ teams. That created new opportunities for girls across the state who wanted to play sports in high school. But Seldin never had her chance.

When Seldin was pushing to be on the team, the high school tennis coach at the time — Arthur Christensen — was a supporter. But Christensen left before Seldin joined the team, and her new coach was not as welcoming, according to an anecdote Seldin has told reporters over the years.

Early in her inaugural high school season, the new coach had the team run a drill that required players to climb up a stairway on their hands while another teammate held their legs up like a wheelbarrow as they climbed. During Seldin’s workout, her teammate intentionally let go of her legs.

“I had the wind knocked out of me. It took me a minute to get my bearings. I didn’t cry in front of them,” Seldin told the Jewish Standard. “I walked out of the door, I walked out of the school, and I went home to my mom. When I got home, I said ‘This is not for me.’”

Though Seldin’s high school career was short-lived, she didn’t stop playing. She went on to play at Syracuse University, and was the school's first woman to receive an athletic scholarship to play tennis. She was one of the first six female athletes to receive a scholarship, period. By 21, she was a certified professional with the United States Professional Tennis Association. And even with two titanium knees, Seldin has continued to play well into her 60s.

Women & Sport:How gaps in research are hurting history of the women's game

In many ways, Seldin’s story can serve as a cautionary tale for future trailblazers and pioneers.

Seldin accomplished a significant feat when the NJSIAA changed its rules for co-ed play — even though she never actually got to enjoy the fruits of her own labor. Her actions were the first steps in a marathon towards gender equality in sports.

This happened in 1972 — months before Title IX was passed, and a year before Billie Jean King’s “Battle of the Sexes” match against Bobby Riggs. In no small way, Seldin helped pave the way for the sport to evolve into what it is today — one that includes several female icons, like Serena Williams.

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Teaneck NJ tennis icon opened doors for future Serena Williams'