Women's soccer kicks back against 'epidemic' of ACL injuries

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup — which concludes on Sunday — has set viewership records around the globe.

It’s a testament to the growing worldwide popularity of the women’s game — sparked in large part by the success of the U.S. Women’s National Team, which entered the tournament as the two-time defending champion. And while the 2023 USWNT was eliminated in the knockout round of 16, when Sunday's final match crowns a new champion, there will be a vast international audience tuning in.

As successful as the quadrennial soccer tournament has become internationally, prior to this year’s event, many of the sport’s most prominent figures have been voicing concern about a troubling trend: an epidemic of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears.

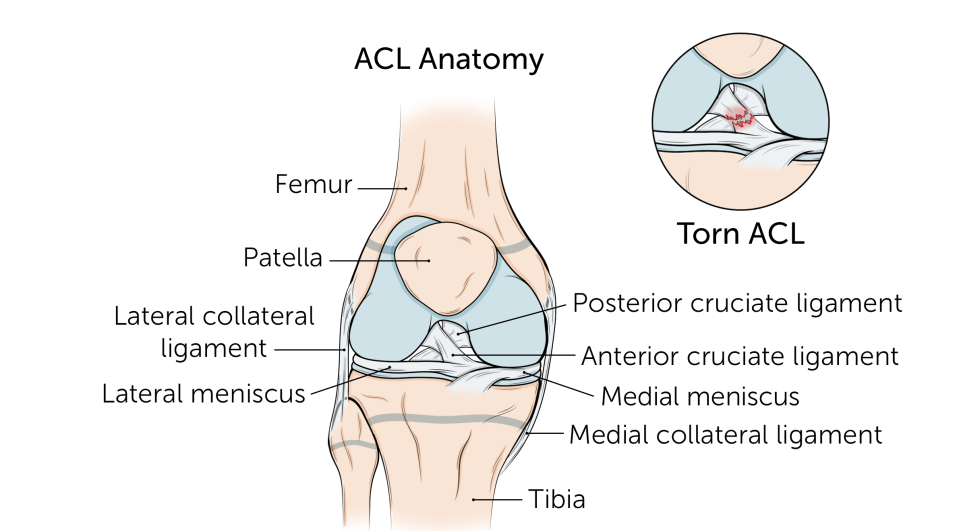

The ACL is one of the two dense bands of tissue running through the knee joint that helps connect thighbone to shinbone. The ligament is elemental in stabilizing the knee and resisting pressures that would twist the leg's architecture out of position and is most commonly injured in sports during sudden stops, changes in direction, jumping or landing.

More soccer news: InternatiNOLES: Who competed in the FIFA Women's World Cup from Florida State

Several studies show that elite female soccer players may be up to 4 to 6 times more likely than their male counterparts to suffer ACL tears.

For competitive athletes, ACL tears always require surgical repair that can take anywhere from nine to 12 months (or more) for a player to recover from.

Several top players from England, France, Canada, the Netherlands and the U.S. have been felled by ACL tears in recent months, which diminished some of the event’s star power. In all, more than two dozen prominent players from qualifying teams were out with ACL tears.

That included U.S. mainstays Christen Press and Catarina Macario.

"I think the amount of ACL injuries in professional women's soccer in the last two years just been shocking," Press said during a recent interview on ESPN's Futbol Americas. "And I think ... if this happened [to these caliber of players] on the men's side, we would've immediately seen a reaction to see how are we going to solve this and figure this out and make sure that these players are going to be available at the biggest moments of their career."

The New York Times noted that Dutch star Vivianne Miedema, who also missed the tournament, said earlier this year that some 60 female professional players in Europe had torn their ACLs this season: “It’s ridiculous. Something has to be done.”

Figuring out what that “something” is, though, is the challenge facing players, coaches, trainers and doctors.

Possible causes for increased ACL injury risk in women

A recent report in the Journal of Orthopedics and Orthopedic Surgery notes that 1 in 19 women soccer players tear an ACL.

The medical community has several working theories as to why this injury is so prevalent in the sport.

An ESPN report before this year’s World Cup broke down six of them thusly:

“Physiological differences between men and women. In women, the ACL tends to be smaller, and the notch in the femur that the ACL passes through tends to be narrower. That leaves less room for the ACL to move, which means a greater likelihood of impingement on the ACL, and thus more risk of injury.”

Environmental factors: Grass vs. artificial turf, temperature, precipitation, style of cleats (molded or studded). (Advocates for the women’s game point out that it’s only been in recent years that manufacturers have started designing cleats specifically for women.)

Hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle. Some experts believe this can affect the laxity of ligaments.

Genetics (i.e., if a parent tears an ACL, the child might be at higher risk to do likewise).

Lack of access to “resources such as quality facilities and knowledgeable coaches and training staff.”

Biomechanics and the kinetic chain — that is, how an athlete moves, runs, jumps, cuts, lands, etc.

More Health Matters: Why did World Health Organization call this popular artificial sweetener 'possibly carcinogenic'?

According to Dr. Marc Cullen, an orthopedic surgeon and sports medicine specialist with Mass Brigham General Hospital in New Hampshire, “Research has shown that ACL injury rates in women are influenced by factors such as landing position and valgus alignment.”

With the former, he explains that “when landing from a jumping position, female athletes tend to land with the knee in extension, which transfers the force of impact to the knee joint. Men tend to absorb more of the energy of impact by landing with their knees in a flexed position.”

In addition, because women tend to have increased knee valgus — i.e., how the knee joint is angled — Cullen explains that “this alignment leads to more stress to the knee ligaments.”

Preventing ACL tears in women's soccer

Doctors, trainers and biomechanical experts all advocate for a sport-wide establishment of specific conditioning exercises and pre-competition protocols for elite female players to follow.

Ones designed specifically for the female anatomy.

Sports performance expert Dr. Holly Silvers-Granelli told ESPN that this includes addressing such easily fixable factors as women tending to have a muscle imbalance between their quadriceps muscles and gluteus/hamstring muscles.

In addition, coaches of female players and club managers need to be taught — and convinced to emphasize — pre-practice and pre-game dynamic training exercises for all their players.

"You can advise a prevention program and teach [a dynamic warmup] as much as possible, but we've got to get people to do it, and it can't be just going through the motions," Denver-based orthopedic surgeon Dr. Rachel Frank told ESPN. "It can't be five minutes of running around the field doing some single leg hops and calling that a prevention program. It's got to be time and dedicated effort. And I think in 2023, time is a commodity, and if a training session for a team is 90 minutes, 20 to 30 of those minutes need to be focused on this prevention program.”

Whether the recent spate of ACL injuries in the women’s game will spur meaningful reform, only time will tell.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: women's world cup missing stars because of ACL injuries