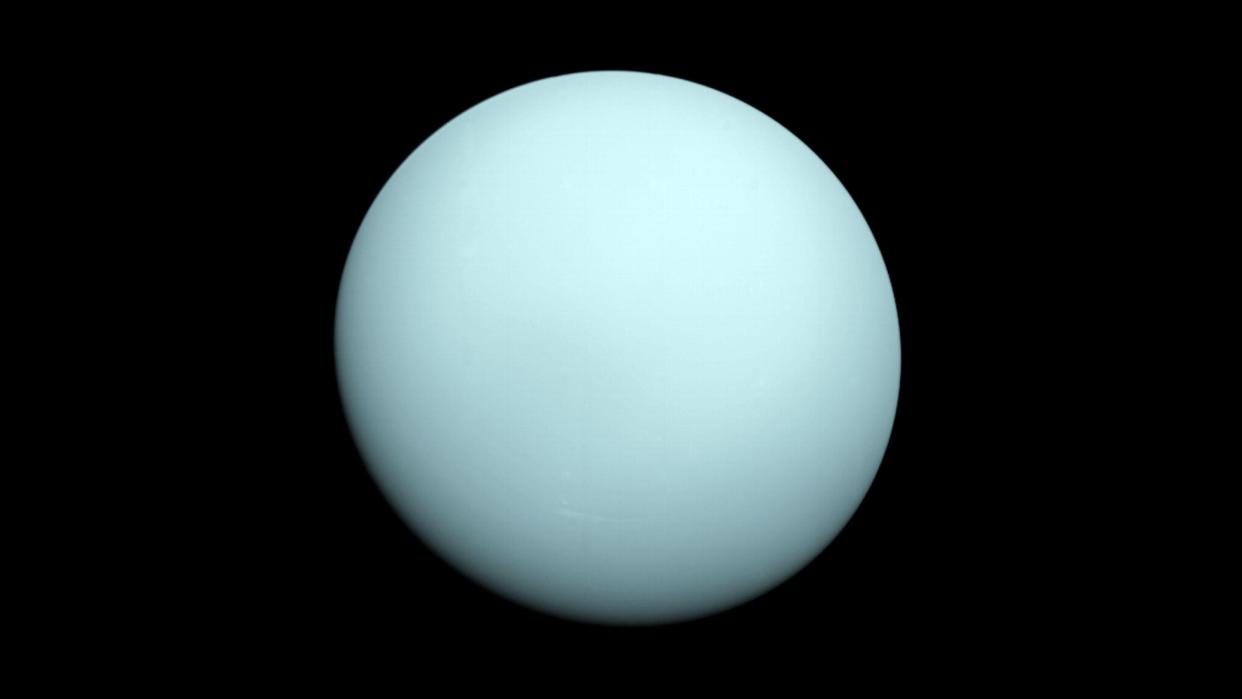

Wonder what it's like to fall into Uranus? These scientists do, too

What would it be like to fall through the clouds of our solar system's ice giants, Uranus or Neptune? Well, no one truly knows — but we might be close to finding out.

We have landed on, crashed into, or descended into the clouds of all of the planets in the solar system except for two: Uranus and Neptune. The farthest planets from the sun, these worlds are still shrouded in a certain degree of mystery. This may soon change, however. That's because both NASA, in the 2023-2032 Planetary Sciences Decadal Survey, and the ESA, in the Voyage 2050 programme, have stated that a visit to these outer planets is a high priority.

To that end, simulated probes can help us understand what descending into the clouds of these planets might entail.

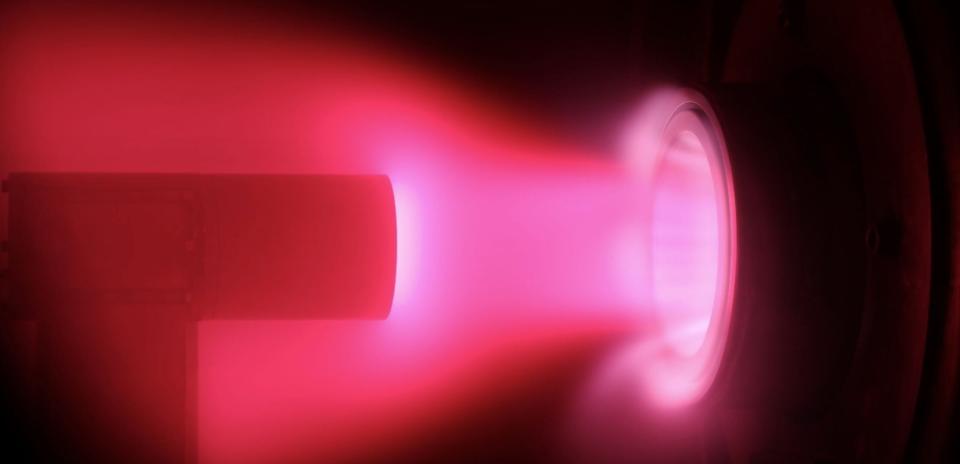

As such, scientists recently simulated a probe descending into the atmosphere of the two planets. The tests took place at the hypersonic plasma T6 Stalker Tunnel at Oxford University and the University of Stuttgart’s High Enthalpy Flow Diagnostics Group’s plasma wind tunnels.

Related: Uranus up close: What proposed NASA 'ice giant' mission could teach us

The T6 Stalker Tunnel is the fastest wind tunnel in Europe, reaching test speeds of 20 kilometers per second (12.4 miles per second.) These tests simulated what a probe descending into the atmosphere of Uranus or Neptune would need to contend with, including heat fluxes and convective heating. Even though the atmospheres of these icy giants are very cold, a probe would heat up significantly from entry into the atmosphere. And the rate of such heating is orders of magnitude higher than anything ESA, for instance, has had to deal with so far.

The tests have already managed to simulate speeds of 19 km per second (11.8 miles per second), but further tests will simulate actual entry rates of 24 km per second (14.9 miles per second.) This speed is equivalent to the speed required for a probe to orbit the ice giants.

"To begin designing such a system we need first to adapt current European testing facilities in order to reproduce the atmospheric compositions and velocities involved," Louis Walpot, an aerothermodynamics engineer at ESA, said in a statement.

Related Stories:

— Infrared aurora on Uranus confirmed for the 1st time

— The rings of Uranus are being held back by its pesky moons

— Weird dark spot on Neptune may have a bright spot buddy

Unlike their larger siblings Jupiter and Saturn, Uranus and Neptune contain a notable amount of heavier elements, along with significant levels of methane, the latter of which turn their clouds blue. These planets may also harbor oceans of liquid within their atmospheres and experience diamond rain.

Nonetheless, Uranus and Neptune are the least understood planets in our solar system, so any probe sent over there would give us enormous information about the worlds' natures. Plus, learning about these ice giants may also help us better understand planetary system formation.