Woods: Black history is part of our history. Only for much of our history, it hasn't been.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

As we entered February, with Florida in the middle of the latest news about education and Black history, I couldn’t help but think back to another month.

In June, a month when most kids are happy to avoid being inside a school, about 100 teenagers from all over town chose to gather at Stanton College Prep for a Duval County Public Schools program.

These students spent a couple of weeks immersed in projects that involved studying local African American history, researching it, writing about it, and thinking of interesting ways to present it to future students.

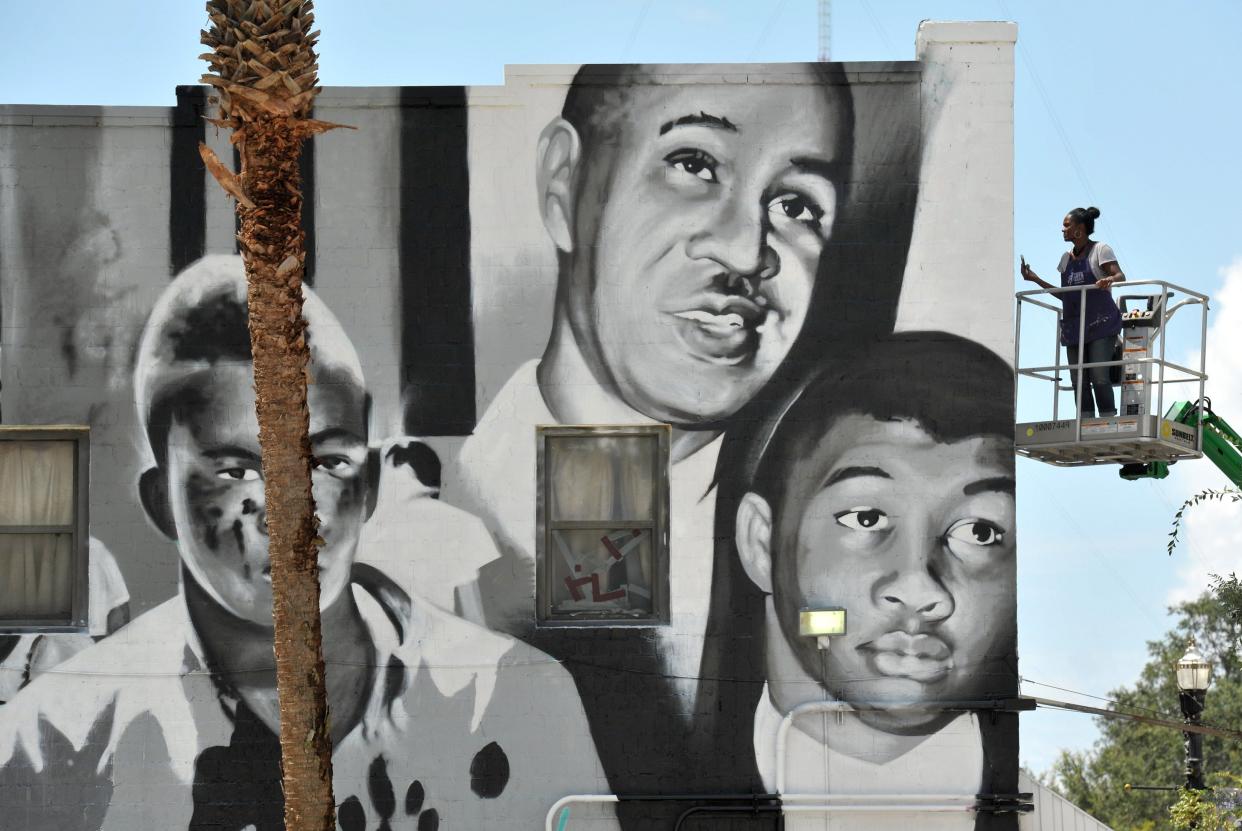

The topics involved the history of LaVilla, Norman Studios, J.P. Small Stadium, James Weldon Johnson, Rutledge Pearson, Eartha White, Gullah Geechee, Ax Handle Saturday and more.

When I spent some time with the students the last two summers, I was struck by several things. How excited they were to be doing schoolwork. How their projects included not only impressive research and original interviews, but often technology far beyond my capabilities. And, perhaps most significantly, how much of what they learned was new to them.

One of the students described the process as being like a scavenger hunt.

“I’ve lived in Jacksonville my entire life, and I didn’t know most of this,” she said. “It wasn’t taught in classrooms.”

Other students made similar comments. And this was part of the goal of their summer projects, to help create curriculum that would allow future students to learn about these local people, places and events.

So this came to mind when Gov. Ron DeSantis held a press conference in Jacksonville after the Florida Department of Education said it wouldn’t allow an AP Black History class to be taught in Florida schools.

The governor and state officials pointed to some details in a pilot version of the class and said it lacked “educational value.”

“We want to do history, and that’s what our standards for Black history are,” DeSantis said. “It’s just cut and dried history. You learn all the basics. You learn about the great figures, and you know, I view it as American history. I don’t view it as separate history.”

When the College Board released the official curriculum for the course Wednesday, it was stripped of some of the subject matter cited by Florida officials. And I’m not going to attempt to delve into what is or isn’t in it, or to compare it to the many other AP courses. I don’t have that insight or expertise.

But it’s worth thinking about the second part of the governor’s statement, about simply viewing Black history as part of American history. That didn’t get nearly the attention, maybe because that isn’t controversial. It sounds like it makes perfect sense. Black history is a part of American history. American history includes Black history, right?

The problem is that this often has not been the case. Take the history of this area, and of a city that recently celebrated turning 200. It isn’t simply a matter of what is or isn’t taught in classrooms today. Or even a matter of what was or wasn’t taught in classrooms for much of those 200 years.

When I met with students in the summer program, they asked for suggestions on how to find original source material about things like Hank Aaron playing in Jacksonville or A. Philip Randolph leading the March on Washington.

I told them when I’m researching a story about something in the past, I love going down the rabbit hole of looking at microfilm from old newspapers — but that when it comes to African American history, that process often is a revelation about how something was covered or, even more likely, how it wasn’t covered.

Newspapers have been described as “the first draft of history.” But that first draft often didn’t include Black history.

It isn’t just that the Times-Union and Jacksonville Journal largely ignored the ugliness of what happened on a day like Ax Handle Saturday in 1960. The daily papers largely ignored celebrations like the one that happened on a Saturday a few years later.

In 1964, the same year that Martin Luther King came to St. Augustine, Jacksonville’s Bob Hayes won two gold medals in the Tokyo Olympics. When Hayes came home and there was a parade, the Times-Union’s editor wanted to leave coverage of it to the Star Edition, distributed to African-American readers.

The Times-Union ultimately did cover it. A photo ran on the front page. It was, the late Jessie-Lynne Kerr recalled years later, one of the first times an African-American had appeared on the paper’s front page without having committed a crime.

To act as if American history, or Jacksonville history, has automatically included Black history … well, it defies history.

Giving a fuller picture of history isn’t about making any students feel discomfort or guilt about events that happened long before their life (an element of the “Stop WOKE Act”). But teaching history also shouldn’t be about avoiding the uncomfortable, telling only feel-good stories.

History isn’t cut and dried. It’s complicated and messy. It’s inspiring and it’s depressing. It’s beautiful and it’s ugly.

When it’s taught well, it also is something else: interesting.

That's one of the things that comes to mind about Black history in Northeast Florida. There are so many fascinating pieces, so many stories worth telling.

From Fort Mose to Cosmo to American Beach. From Anna Kingsley to Zora Neale Hurston. From the red-capped porters on the trains to the Red Caps on the baseball field in Durkeeville. From the movie “Flying Ace” being filmed at Norman Studios to the modern-day movie “Devotion” telling the story of a Navy pilot Jesse L. Brown who made history here. From Alton Yates having the courage to sit in a rocket-propelled sled and help America race to space to … Alton Yates having the courage to sit at a lunch counter in downtown Jacksonville.

It’s all part of our history, right?

Only throughout our history, it often hasn’t been.

mwoods@jacksonville.com

(904) 359-4212

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: If Duval Florida kids don't learn Black history, they're missing out