Woods: CCC is an American success story. Okefenokee Company 1433 is an overlooked chapter

When I spend time in America’s public lands, I’m never surprised to learn that something I’m seeing or using — a picnic table, a visitor center, a trail — goes back to the Great Depression and the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps.

Over a nine-year span from 1933 to 1942, the New Deal program took more than 3 million unemployed young American men and put them to work. They were given food, clothing, shelter and $30 a month, with the expectation that at least $25 be sent to a dependent. They worked in national parks across the country. They helped create more than 700 new state parks. They paved roads, planted trees, cut trails, fought fires, built campgrounds and much more.

So it wasn’t a surprise to learn that in 1937, after President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge, a CCC company was sent to southeastern Georgia to work in and around the largest national wildlife refuge east of the Mississippi

But what I didn’t know until a recent visit to the Okefenokee: Company 1433 was an all-Black unit.

From 1937 to 1941, about 200 members of Company 1433 worked on bridges and roads, planted trees, built facilities that are still in use today, and cleared the Okefenokee Wilderness Canoe Trail — all of which helped to open up the Okefenokee region for tourism and commerce.

“They played a pivotal role and yet were almost completely overlooked,” Jennifer Berglund said.

Berglund, a National Geographic explorer whose work has taken her to all seven continents, is leading an effort to change that. She’s the manager of the Company 1433 Project.

Company 1433 Project

The project stems from Michael Lusk, manager of the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge, stumbling upon a footnote about Company 1433.

There were three CCC camps in the Okefenokee. At the time, the local newspapers published detailed accounts of the two all-white camps. The names of who was there, what work they were doing, what they were eating for dinner, and more.

"For Company 1433, there's almost nothing," said Jessica Neal, archivist for the Company 1433 Project.

At a virtual launch for the project, timed to coincide with Black History Month, Berglund thanked Georgia Sen. Raphael Warnock for securing funding. In a recorded message, Warnock said: “ You are shedding light on an overlooked chapter in our state and nation’s history.”

The overall CCC story certainly isn’t overlooked in American history. It often is recalled as an American success story, an economic and spiritual bridge from the Great Depression to World War II, with lingering impacts across the country. Not just on public lands, but on surrounding areas. Many of the young men had never left home before. Many would never return, choosing to put down roots where they did their CCC work.

But while more than 200,000 Black men served in the CCC, they often are missing from the historical records and retelling of the CCC story. The same is true of about 85,000 Native Americans in CCC Indian Division camps and 8,500 women in the “SheSheShe” camps organized by Eleanor Roosevelt.

Uncovering the story

So telling the story of Company 1433 isn’t as simple as, well, telling the story. Much of it is unknown, even to those close to where it happened.

At the launch, Waycross Mayor Michael-Angelo James and Waycross Tourism Manager Patrick Simmons, both African-American, said they weren’t aware of Company 1433 before this project began to take shape.

“It's all new information to me,” Simmons said. “It was very fascinating to realize the contribution that African Americans made in the swamp.”

To tell the story involves first uncovering it, finding descendants of Company 1433 in the area today, looking for old photos tucked away everywhere from the National Archives in Washington D.C. to family albums in Folkston and Waycross.

'Where land meets water'

Neal, archivist for the Company 1433 project, is leading that effort. Berglund describes her as the "heart and soul" of the project.

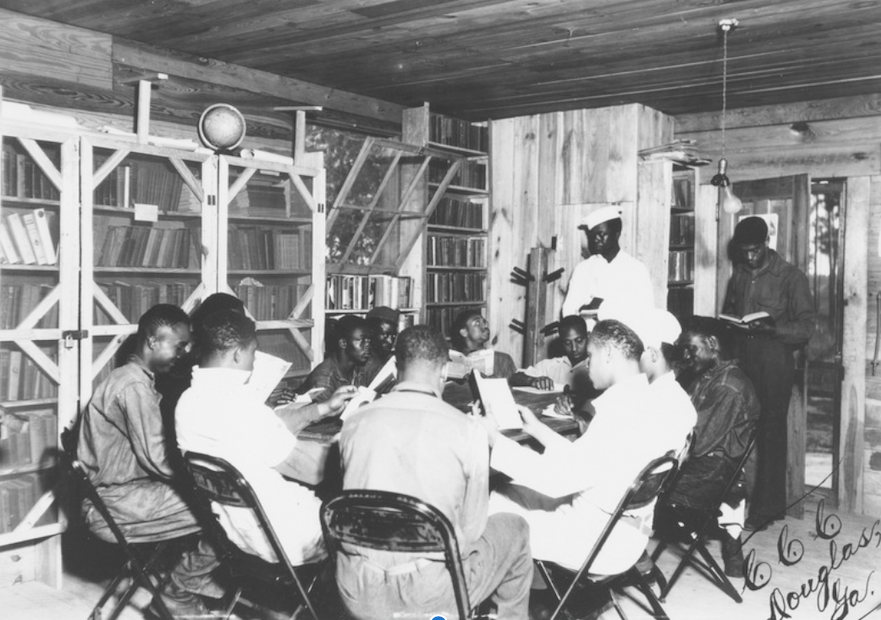

It is telling that at this point, even after Neal made a trip to the National Archives, they have four photos of Company 1433.

“Three are kind of grainy,” she said. “And then we have this image here.”

She shows the one clear photo they have. It was taken in Douglas, Georgia, before Company 1433 relocated to the Okefenokee. It’s of a group of about a dozen men sitting and standing around a table inside a building. One wall of the room is full of books. The men all are reading books.

She did find hundreds of other unidentified photos from all-Black units. But that's still a sliver of the documentation for other units. And that hole in history is part of what drew her to working on this project.

She’s from Mobile, Alabama. And she says a project involving a national wildlife refuge and its partners, set in a place where water and land meet, feels like a “full-circle moment” for her.

Her first role as an archivist was with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Hawaii, working on the James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge and the Kilauea Point National Wildlife Refuge.

“As a child of the Gulf Coast, one aspect of the Company 1433 Project that attracted me was the opportunity to center my archival lens on the engagement of land and water by Black folk in an intentional and focused way,” Neal said. “There is, and will always be, a sacredness of where land meets water. There's a balance there that is unlike any other pairing for me.”

That’s part of this story and, more broadly, history.

“There is a long history of people of color having a deep and intimate relationship with the earth as caretakers, as cultivators, as farmers, as ecologists and conservationists,” Neal said.

While the Okefenokee NWR was established as a refuge for migratory birds and other wildlife, it has a history of being a refuge for human beings.

Neal notes that Native Americans took refuge there during the Seminole Wars of the 19th century, and enslaved African Americans took refuge there as they tried to escape to freedom.

Today the largest blackwater wetland in North America remains a wildlife refuge. But it also is a place where everyone can find a bit of refuge from the modern world. And that's partly thanks to FDR, the CCC and an almost forgotten unit.

mwoods@jacksonville.com, (904) 359-4212

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Stories of Black Civilian Conservation Corps workers often overlooked