Woods: Nobody is saying slavery was good? History teaches some said exactly that.

“Slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

That’s the sentence that, once again, put education in Florida in the national spotlight.

When the Florida Department of Education released new African American history standards last week, there was a flurry of complaints about omitting or rewriting history. While it was about much more than one benchmark clarification of standards for middle school students, that quickly became the focus.

State officials eventually responded by issuing a statement that said, in part, “Any attempt to reduce slaves to just victims of oppression fails to recognize their strength, courage and resiliency during a difficult time in American history. Florida students deserve to learn how slaves took advantage of whatever circumstances they were in to benefit themselves and the community of African descendants.”

To illustrate this, the statement included 16 examples of historic figures who developed skills while enslaved.

One problem. Well, more than one. But, to start with, many of those on the list didn’t develop said skills while enslaved. Some weren’t even enslaved at all.

According to the Tampa Bay Times, some critics noted that nearly half of the people highlighted by the state never were enslaved.

So if this were a pop quiz — quick, come up with a list of historical figures who developed skills while enslaved — the state wrote the question and still failed.

F is for Florida.

'Factual and well documented'

But to a degree, that’s just a side note in the larger picture of this latest education saga. State officials insisted that saying some slaves developed skills from which they benefited “is factual and well documented.”

Here’s what else is factual and well-documented: Long before they were enslaved, many had their own languages and skills, passed down while living on their native lands. The Gullah Geechee, for instance, had a wide range of skills involving irrigation techniques, metallurgy and herding. In some cases, those existing skills are precisely why they were coveted by slave traders.

So go ahead and teach Florida students that some slaves learned skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.

But also teach Florida students how this particular fact has been used to distort and affect history.

In the wake of this latest news, I spent some time on Newspapers.com, a digital database of newspaper archives, searching for stories that mentioned slavery and skills.

One of the first stories that popped up was about slave tags. To oversee the slave trade and generate some added revenue, some cities issued tags. The slaves had to wear the copper tags around their necks at all times. The tags typically included a number and one word — the slave’s primary skill.

References to the significance of slaves developing skills could be found in political speeches, monument dedications, newspaper op-eds and reprinted student essays.

I found a story, published nearly a century after the end of the Civil War, that said on plantations across the South, slaves had learned many skilled trades, becoming carpenters, blacksmiths, farm hands, weavers and house servants.

“It’s perhaps stretching one’s credulity to suggest that negroes, captured in Africa, brought across the ocean, sold into slavery, never more to see their native land, fared better thereby,” it said. “But nevertheless, over there they were unclothed, ignorant, superstitious, without vision and living a life of hazardous vicissitude. Over here they were clothed, taught civilization’s ways, trained in worthwhile labor, and were living a life of crude comfort, without hazard.”

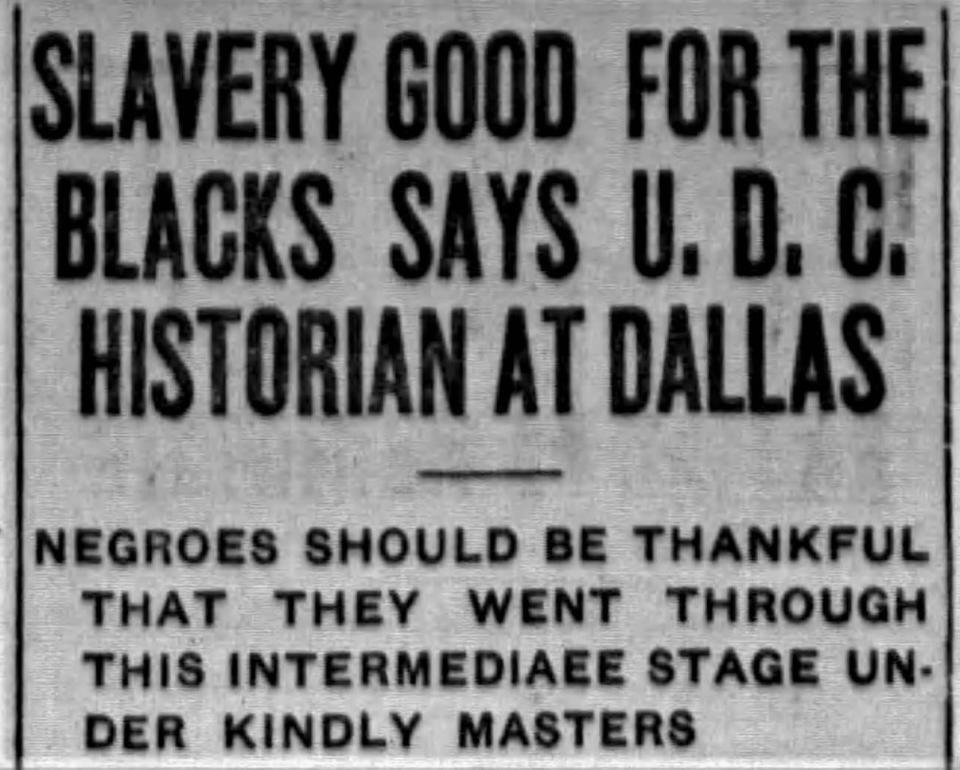

Generations after the end of slavery, you can find this perspective repeated often. I found headlines that said things like “Slavery Protected the Negro” and stories like the one in the Orlando Evening Star in 1916.

It said that Miss Mildred Lewis Rutherford, the historian general of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, addressed the group’s convention. The topic of her speech: slavery not only was good for the South, it was good for the slaves.

Among her quotes: “The black man should thank God for the institution of slavery as it existed in the South — the easiest road any slave people ever passed from savagery to civilization under the kindest and most humane masters.”

She went on to say that the policy of Reconstruction in the South, along with the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution, destroyed civilization. She then apparently went on a bit of a tangent, about how she longed for the good old days.

“It is now, hurry, hurry, hurry, to keep up with the telegraph, the telephone, the automobile, the moving picture show — yes, and the flying machine, too,” she said. “How restful the old life was.”

How restful. Except maybe for some of those on the plantation.

Dateline: Jacksonville

In 1937, several Florida papers ran a story with a Jacksonville dateline and a headline that said: “Florida Once Was the Spot Where Slaves Were ‘Tamed.’”

It told the story of how Zephaniah Kingsley bought an estate on Fort George Island in the early 1800s and kept a fleet of schooners running between his plantation and Africa, buying thousands of human beings for about $25 apiece and eventually selling them for $1,000 to $1,500.

It noted that Kingsley wrote a book in which he defended slavery, not only by saying it was “of great economic benefit to society” but by saying that it “tamed” the enslaved, giving them useful language and occupational skills.

The remains of 25 tabby cabins can still be found on Fort George Island.

It’s one of the places in our backyard that can help teach students about some of the most complicated pieces of Florida and American history.

It’s a place where it was illegal for the people who once lived there to record their own history.

When there was criticism last week about teaching modern-day Florida students that “slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit,” one of the responses was quite simply that this is a fact — nobody is saying slavery was good for the enslaved.

This might be true. But this is exactly what some people were saying many generations after the end of slavery, preaching it from pulpits, teaching it in schools and, in some instances, applying it for personal benefit.

That also is a fact — one that's important to teach in Florida.

mwoods@jacksonville.com, (904) 359-4212

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Teach Florida students how slavery facts have been used in past