These woods were a crime scene. A mother's love transformed it into Jennifer's Garden.

Editor’s note: This article describes abusive dating relationships and the violent murder of a high school student. Call the National Teen Dating Abuse Helpline at 866-331-9474, text “LOVEIS” to 22522 or visit loveisrespect.org for immediate, confidential assistance.

Tucked in the woods at the neighborhood’s edge, past a grassy clearing, stands an unexpected retreat — a spot bursting with colorful flowers, shimmery wind chimes, brightly painted rocks and sprightly garden statues, all nestled among the trees.

One of the neighborhood kids calls it the Fairy Garden.

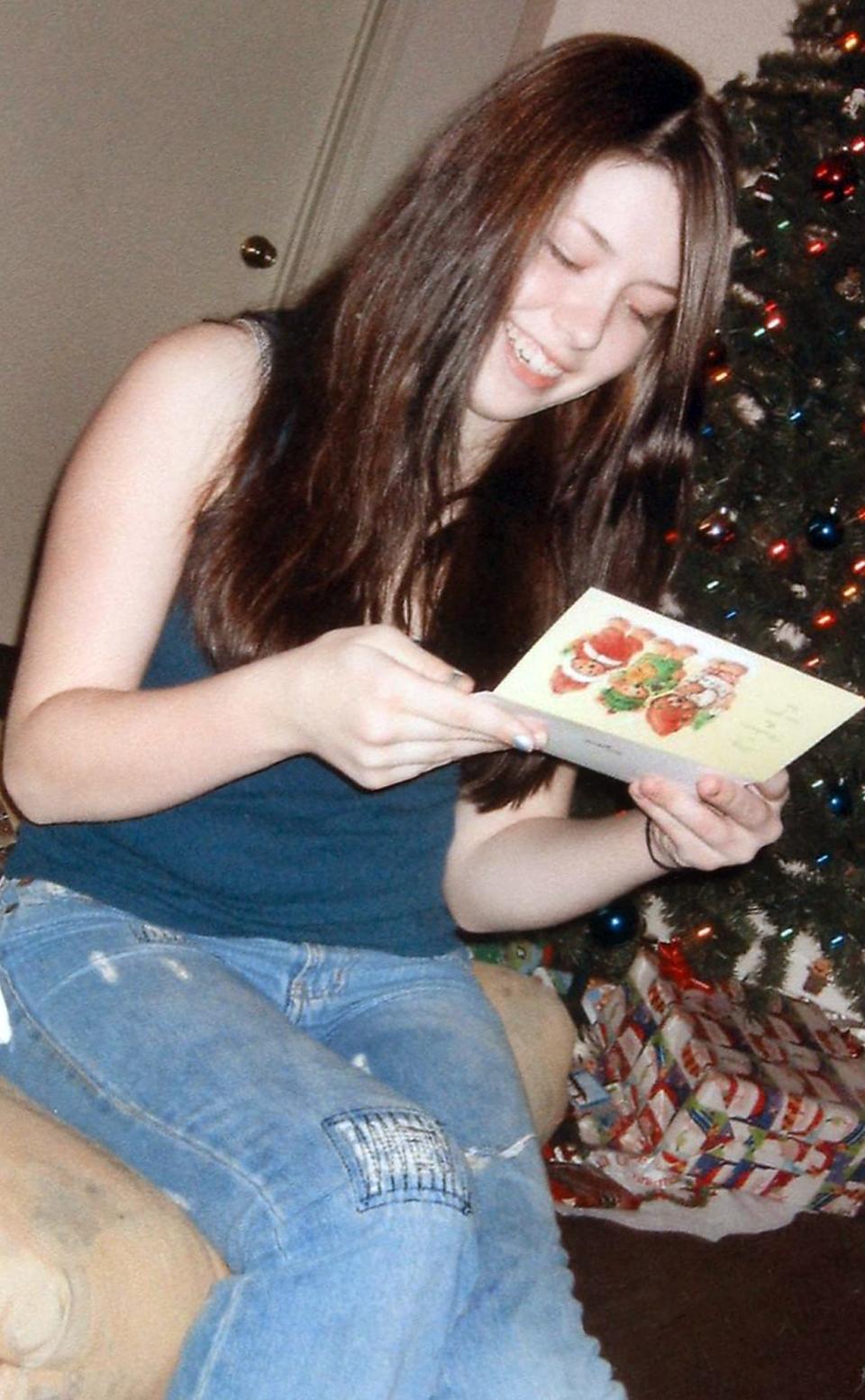

Jennifer Crecente would have loved that.

“To me, this is Jennifer's Garden, that’s it,” said her mother, Elizabeth Crecente, who created this enchanted spot and tended it for the past 17 years, with the loving help of others. “I rarely think about the fact that she died here.”

It wasn’t just a death, but a horrific murder on Feb. 15, 2006, a few months before 18-year-old Jennifer would have graduated from Bowie High School. Her ex-boyfriend, Justin Crabbe, lured her to these woods between their homes in Southwest Austin, and he then killed her with a sawed-off shotgun he had hidden in the brush.

Even now, no one understands why Crabbe, then 18, killed one of the few people who was trying to help him.

“You left us with the vision of our child, alone in those woods and unwhole, and it will never mend,” Elizabeth Crecente told Crabbe at a 2007 court hearing, when he took a plea deal for 35 years in prison. “That darkness will never be fully lit. Why didn’t you just leave her alone, Justin?”

Crecente’s healing began with reclaiming that space, turning the scene of Jennifer’s death into a celebration of the teen’s life, a place of joy and peace. It offered her a path from despair to advocacy for preventing teen dating violence.

Jennifer used to tell her mother, “I love you more than dirt,” and it meant affection of the highest order. After all, what else on this planet is more abundant than earth?

Each time Elizabeth Crecente returned to the garden, coaxing life out of the soil, that love was returned.

But now Crecente is pouring her energy in another direction: This month the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles is considering whether Crabbe, halfway through his sentence, should receive parole. Crecente told Crabbe in 2007 that she would fight his release at every parole hearing.

She is keeping that promise.

“I would like the parole board to look at any crime scene photo and tell me that he deserves to get out after 17 years,” Crecente told me, alluding to the vicious nature of the shooting. “I don't see how anybody could look at one of those and even consider parole.”

Crabbe: ‘I decided to help myself’

Crabbe is no longer the dangerously disturbed teen whom Crecente knew, but a 35-year-old man who has spent half his life behind bars. Writing to me from prison, Crabbe said he used those years and every resource he could find to remake himself.

“As I got into my twenties things became starkly apparent to me and I realized that I needed to make some positive changes,” wrote Crabbe, who now lives at the Stevenson Unit, a prison complex that houses up to 1,400 inmates outside Cuero, halfway between San Antonio and the Gulf coast. “So I decided to help myself, and change my own life, and not let this place consume me.”

He provided records showing he earned his GED diploma, multiple welding certifications and a bachelor’s degree in business from the distance-learning program at Adams State University. Now, he is a few credits shy of completing his MBA at Adams State.

He also completed “every course available to me,” including the faith-based Prison Fellowship Academy, a yearlong program about mending relationships and taking responsibility for actions; and Bridges to Life, a 14-week program centered around victims’ experiences. Crabbe said he teaches programs about mental health, sexual assault awareness and suicide prevention to other inmates.

“I've lived through all of those things, and it helps me to help others,” Crabbe wrote.

He said it has been 12 years since he had any disciplinary infraction, although I can’t confirm that, because the prison system is not allowed by law to divulge that information.

I had other questions for Crabbe. Why did he kill Jennifer? How does he make sense now of those actions? What should justice look like for himself and for those who loved Jennifer?

On the advice of his attorney, Crabbe did not respond to those questions while the parole review is underway.

“That is a glaring omission,” said Scott Hampton, a New Hampshire-based psychologist and executive director of Ending the Violence, who reviewed the case at my request. He works with domestic violence and sexual assault offenders in county jails, focusing on getting them to take responsibility and develop healthier behaviors.

Hampton said Crabbe needs to recognize that he gave Jennifer a death sentence with no chance for appeal. Now Crabbe is asking for a break on a prison sentence that doesn’t match what he took from his victim.

“I want (Crabbe) to see that and say, ‘I understand how unfair that is. Now let me tell you what my plan is to try and make this up to her family, to society, and to keep other women safe,’” Hampton said.

Troubling signs of abuse

Crabbe met Jennifer at Bowie High School, and they dated on and off for a couple of years. At that same time, court records show, school counselors found Crabbe to be "emotionally disturbed." He was using drugs, fighting with family members and cycling in and out of the juvenile justice system.

“Their relationship was very much centered around (Jennifer) saving him … and he was telling her, ‘You're the only one who can save me,’” Crecente said.

Jennifer had a big heart and a bold sense of humor. Classmates were mystified when Jennifer developed that intense teenage love for Crabbe, whom they remembered as withdrawn and unwilling to even make eye contact.

“I'm like, ‘What are you doing with this kid?’” recalled Karli Wills, one of Jennifer’s friends. “But true to her personality, he had issues and she wanted to help him.”

In time, though, Crabbe became controlling. He didn’t like Jennifer talking to certain people or wearing certain things.

“She couldn’t go places without him keeping tabs on her,” Crecente said. “She couldn’t just be at home or eat dinner with us without him texting over and over and over.”

Then, as Jennifer started her senior year of high school, Crabbe was shipped off to a court-ordered, 90-day boot camp after breaking into a home to steal guitars and electronics. The program was meant to be a wake-up call and a second chance, an alternative to a yearslong prison sentence.

Friends said a happier Jennifer resurfaced while Crabbe was gone. When he returned — less than two months before the murder — Jennifer decided not to date him, but to try to help him as a friend.

It can be hard for a victim to disengage, Hampton noted, because the abuser has drilled into her the idea that "the only reason he's not better is because she's not helping him enough. She's not doing things quite right. And he really wants her help. He's asking for help. He's pleading for the help."

The relationship became even more volatile in those final weeks. Jennifer's friends barely saw her. Bruises on her neck and chest suggested physical abuse.

Crabbe never gave police a truthful account of Jennifer’s death, let alone a motive for it. After initially denying any involvement, Crabbe told police that he and a friend were playing with the shotgun “like Elmer Fudd” when it accidentally went off, hitting Jennifer.

Later, Crabbe tried to blame Jennifer for her own death, telling his lawyer there had been a murder-suicide pact.

No evidence supported those claims. The forensics showed Jennifer was on her knees when she was shot squarely from behind at close range.

Witnesses told police that Crabbe had talked for months about killing Jennifer, blaming her in some vague way for his problems.

The lack of an explanation haunted Crecente. She had to set it aside.

“You can’t live with that every day,” she said. “It will eat you alive.”

Turning grief into a garden

For weeks after the murder, Crecente returned to the spot in the woods where Jennifer’s body was found.

"I didn't know how to be here, on this planet," Crecente told me. "I really just wanted to go be with my daughter, and so I was out here all night, every night."

Eryn Zavaleta lived nearby. She realized Crecente was out there late one night, so she got a flashlight and went to check on her.

She found Crecente lying on the floor of sticks and dried leaves, sobbing in the dark.

"Can I sit with you?" Zavaleta asked.

Crecente nodded yes.

“I sat down on the ground beside her, and I scooped her up, and I just kind of wrapped myself around her," Zavaleta told me. "We just sat there for a minute, and she just cried."

“Then she said, ‘Can I talk about my daughter?’ And I said yes.”

“I saw this amazing woman living every mother’s worst fear,” Zavaleta told me. But talking about Jennifer helped, and the idea of memorializing her gave Crecente a place to pour her love. That Mother’s Day, Crecente planted pink bougainvillea in what became Jennifer’s Garden.

As the perennials grew, so did Crecente’s spirit and ambitions. She launched a nonprofit foundation, Jennifer’s Hope, to help prevent teen dating violence. Alongside fellow Austin mom Carolyn White-Mosley, Crecente helped champion a 2007 Texas law requiring school districts to develop policies for handling cases of teen dating violence — a measure sparked by the 2003 murder of Ortralla Mosley at then-Reagan High School (now Northeast High).

Crecente speaks to parents and teens, teachers and law enforcement officers, victims' advocates and anyone else who could be touched by abuse. And for the past eight years, she has shared Jennifer’s story with teens on probation in Williamson County who have been ordered to take a class on preventing abusive relationships.

“There’s a lot of crying,” said Stephanie Teinert, a juvenile case manager who used to lead the class with Crecente. “A lot of people who initially weren't participating are suddenly paying really close attention.”

The teens in those classes write messages for Jennifer and Crabbe.

They tell Jennifer: You deserve better. I would stick up for you.

They tell Crabbe: I can’t believe you did that!

But also: You needed help, too.

That’s what Crecente wants, for people who might be abusive to know they deserve help, and to know where to find it.

She hasn’t said anything to Crabbe since his sentencing in 2007. But Crecente never stopped talking to Jennifer. She has boxes filled with notes that people have left at the garden over the years, including some from her. She marks the birthdays Jennifer never had and the holidays she has missed.

“You have given me a life, a purpose that was yours,” Crecente wrote on what would have been Jennifer’s 20th birthday. “I'm grateful for that, but I miss you. I'm in no less grief for your loss. I hold you so near.”

The letters span different seasons of sorrow and hope, but Crecente ends them all the same way, with a profession of love even greater than dirt.

“I love you to the moon and back.”

Grumet is the Statesman’s Metro columnist. Her column, ATX in Context, contains her opinions. Share yours via email at bgrumet@statesman.com or via Twitter at @bgrumet. Find her previous work at statesman.com/news/columns.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Austin mother's love turned a crime scene into Jennifer's Garden