A Woonsocket man was declared incompetent. It took advocates months to get him out of the hospital.

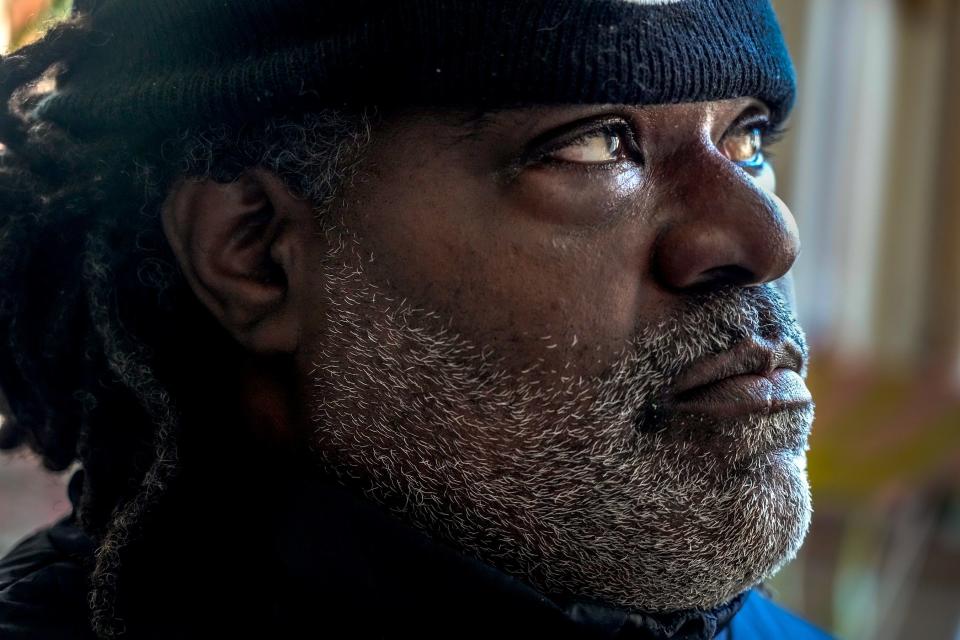

PROVIDENCE – Noel Dandy has been on an odyssey since last May, taking him from the Warwick Motel 6 to the Rhode Island State Psychiatric Hospital, where he was kept for five months and 23 days – a full month longer than he should have after a doctor declared him competent.

And it started when a police officer asked him his date of birth.

Dandy was on his way to work security at the Mathewson Street United Methodist Church when the officer stopped him outside the Motel 6, where he was living in a shelter run by OpenDoors. There was a warrant out for his arrest – on a previous assault charge – and Dandy was taken into custody.

That case was ultimately dismissed, but Dandy was kept at the Adult Correctional Institutions on a warrant for a separate 2021 case, where he was accused of biting a man at Crossroads Rhode Island. Dandy insists it was self-defense and that the other man had grabbed him by his face.

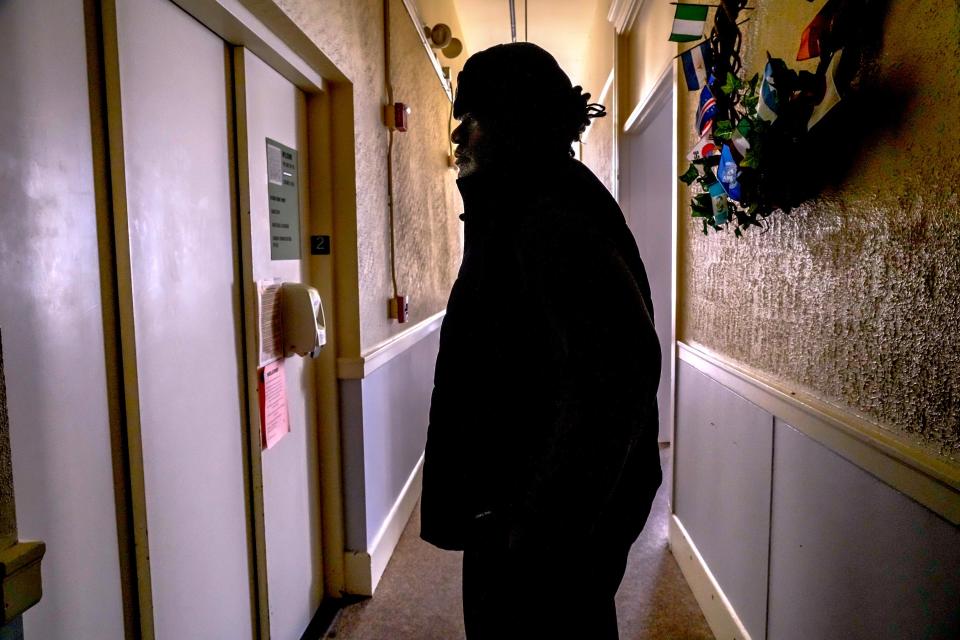

The legal trouble thrust Dandy into a system and process that is kept largely out of the public eye, where people can be held, and even given medication, without their consent.

“I was terrified," Dandy, 54, recalled. "I didn’t know if I was going to get out of there."

'There's something wrong with you'

Over the course of the Crossroads case, Superior Court Judge Richard Raspallo had ordered Dandy to undergo a competency evaluation after he went against his then-lawyer's wishes and pressed to go to trial and clear his name.

“The judge just looked at me and said, 'There’s something wrong with you. You’re going for an eval,'” Dandy recalled.

He was released, but when he missed the date to appear for his evaluation, a warrant was issued, leading to his being held without bail in May for violating the terms of his release.

Within weeks, Dandy, who had suffered a traumatic brain injury years earlier in a car crash, was deemed incompetent to stand trial by Dr. Barry Wall at the state Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals. He was taken to the Rhode Island State Psychiatric Hospital by order of Superior Court Magistrate John F. McBurney III. Orders are usually entered with the agreement of the defense lawyer and prosecutor.

“We don’t do it off the cuff,” District Court Judge Pamela Woodcock Pfeiffer said in a recent interview.

The hospital treats psychiatric and court-ordered forensic patients and, in some cases, works to restore their competency through treatment and education so they can participate in their own defense.

They told Dandy he was schizophrenic, delusional and heard voices, he said. His criminal case was continued to December for a six-month review.

In the months that followed, Dandy says he lost everything: his hotel room at the shelter, clothing, earbuds, protein powder, hygiene products and other belongings. He also lost his job at the Mathewson Street church, where he'd been bringing in $473 a week.

Supporters: 'It just feels like he's being railroaded because he is poor'

Private health care, confidentiality and public safety concerns largely keep the systems and legal processes around incompetency away from the public eye.

When an individual is deemed incompetent, it is based on the understanding that they are “likely to imperil the peace and safety of the people of the state” or themselves.

It left Dandy’s supporters from Mathewson Street church with less contact with him than they would’ve liked. They worried about how he would manage his diabetes, which he regulated through a vegetarian diet and exercise.

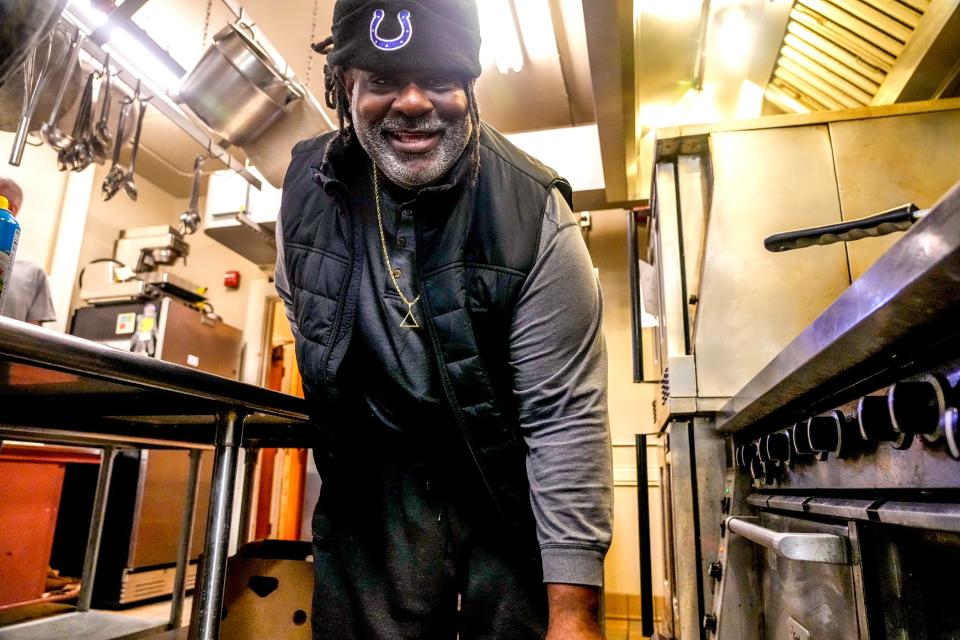

“Noel began helping, and we ended up hiring him,” said the Rev. Duane Clinker, a longtime pastor at the church. “He was gentle, appropriate and trainable. We could leave him in the building alone.”

The church, in downtown Providence, provides refuge, meals and bathrooms to Rhode Islanders in need. On Sunday mornings, it holds a “friendship breakfast” and prayer service that draws hundreds.

“It just feels like he’s being railroaded because he is poor,” Clinker said.

Pamela Poniatowski, an organizer for the Rhode Island Poor People’s Campaign, wondered whether Dandy’s appearance – he's 6-foot-3 and wears his hair in dreadlocks – contributed to his case’s trajectory.

“They’re writing the narrative they want to put forth,” Poniatowski said.

'Am I allowed to object?'

During Dandy’s hospitalization, he also became engaged in a separate, confidential civil certification calendar in state District Court.

The calendar takes place behind closed doors, either on the Pastore Complex campus or at Butler Hospital, and the records are confidential.

In August, District Court Judge Melissa DuBose issued an order substituting the judgment of the court for that of Dandy, based on a petition from a psychiatrist, Dr. Pedro F. Tactacan. In doing so, it empowered the court to allow doctors to administer medications without Dandy’s consent.

“I said, 'Am I allowed to object? Am I allowed to appeal?’ Not one time did I appear before this judge,” Dandy recounted.

According to Pfeiffer, such orders – referred to as petitions for instructions – come after detailed testimony from state mental health providers and input from the Office of the Mental Health Advocate, which represents patients on the civil certification calendar. The patients are often given a chance to speak and consult with their advocate.

"I think we all take that very, very seriously,” Pfeiffer said.

Dandy says he was strapped down and injected with an antipsychotic drug. Clinker and his other backers worried anew about that medication’s interactions with his diabetes care.

“It made me sluggish, slow,” said Dandy, who continues to take the drug as part of his treatment plan but is working with his provider in hopes of getting off it.

The Mental Health Advocate’s Office declined to speak about the specifics of Dandy’s case, due to confidentiality.

Dandy says he was never previously diagnosed with schizophrenia

Dandy admits being aggravated during his initial evaluation based on questions he perceived as stupid and demeaning. He was furious about being arrested in the first place, believing his words and actions were being viewed without context. He wanted to set the record straight.

“I was getting sarcastic," he said. "I wasn’t being nice.”

He said he had never previously been diagnosed with schizophrenia but has occasionally experienced depression, particularly after he had a son while in high school who was adopted.

Other patients wondered why he was there, he said.

“Most of them absolutely belong there. I couldn’t find anyone like me,” said Dandy, who communicated mostly with staff during his stay.

He reflected on the people who visit the Mathewson Street church, many of whom lack housing and have untreated mental health needs.

“I know a hundred people who could use this bed,” Dandy recalled telling the hospital staff.

Supporters fight for Dandy's release

On Oct. 25, Superior Court Magistrate McBurney issued an order declaring Dandy competent, based on a Sept. 29 report from Dr. Ruby Lee of the state Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals.

At 5 p.m. that same day, Dandy was released to the state Department of Corrections and freed on bail to Clinker and his other supporters.

“I was very emotional," Dandy said. "I was filled with tears. If no one was on my side, I’d still be there.”

He credits his Mathewson Street supporters with helping him win his freedom, particularly Clinker.

“He has a really big mouth," Dandy said. "He knows how to complain."

How many people are deemed incompetent to stand trial in Rhode Island?

Over the last five years, 1,419 people have been evaluated by BHDDH, 804 of whom psychiatrists deemed incompetent to stand trial, according to numbers provided by department spokesman Randal Edgar. Those who are admitted to the Rhode Island State Psychiatric Hospital are referred to as “forensic patients” who have been placed on a forensic hold.

Demographic information kept by the state indicates that of those declared incompetent from 2019 through 2023, 53% were white; 25% Black or African American; 17% Hispanic; and 5% Asian.

The average duration of commitment ranged from a high of 215 days in 2021 to 148 days in 2019.

Competency hearings vs. certification

Individuals subject to a civil court certification through the confidential District Court process are ordered by a judge to be treated for a psychiatric illness. They may be ordered to receive treatment through a community mental health provider or a group home, or ordered to be admitted to a hospital. They are civil patients, and their commitment is not related to criminal charges, Edgar said.

Unlike the private certification process, competency hearings are held in the criminal courtrooms. While they are not necessarily confidential hearings, a judge may order the courtroom closed if an individual’s protected health information is being addressed, Edgar said.

People who are found incompetent to stand trial may be held for a period that is no more than two-thirds of the maximum sentence for the criminal offense for which they are charged under state law. That would mean that a person charged with a misdemeanor punishable by a one-year maximum sentence may be held for competency restoration for no more than eight months, Edgar said.

Civil commitment orders are valid for six months.

Retired judge weighs in

Retired District Court Judge Stephen Erickson expressed concerns about the civil court certification process, namely that District Court judges rotate through the calendar on a monthly basis because it yields a higher pay scale.

According to Erickson, the lack of a dedicated judge overseeing the calendar means that no “therapeutic” relationship is developed with the people appearing before the court.

“This is a very draining calendar to be on. You really have to think in a compassionate way and a legal way,” Pfeiffer said.

Different judges differ on how to run the calendar, sometimes with disastrous results for the patients, and standards change from month to month based on the judge, said Erickson, who works as a professor of mental health law at Roger Williams University School of Law and a professor of psychiatry and human behavior at the Warren Alpert School of Medicine at Brown University. Erickson served on the District Court bench from 1990 to his retirement in 2010.

“[S]ome judges treated all the patients as criminals (even though many were not charged or convicted of anything); and for some judges it was just about the money and working a part day,” as the mental health calendar days often end at noon, he said.

The judge can neither be contemptuous of medical opinion or excessively deferential to medical opinion, as either attitude erodes the system and undermines the due-process rights of the patients, Erickson said.

More: Trailblazing R&B group sues `imposter' in RI to protect history

He noted that other states, including Connecticut and Massachusetts, send the judges to where the patients are, instead of requiring that the parties go to a centralized location.

The judges rely on expert medical testimony in making these sensitive rulings that could potentially take someone’s liberty away by having them hospitalized, Pfeiffer said.

“It’s like a trial. … Ultimately, at the end of the day, we have to rely on what we’re told,” she said.

Erickson cautioned that any judge sitting on the mental health calendar should receive specialized training.

Pfeiffer ticked off the trainings District Court judges undergo continually. They have met with BHDDH and Thrive Behavioral Health. They attend specialized judicial conferences. They learn about domestic violence, the effects of synthetic drug and opiates; and how to recognize certain mental health issues.

Erickson also observed that denial is a common part of schizophrenia, though Dandy’s supporters – including Clinker – say they have never seen signs of the illness in him, despite his strong-mindedness.

“A properly medicated schizophrenic with community support who is still in denial can still lead a functional life in the community," Erickson said. "Many people live and prosper with untreated bipolar disorder.”

'There has to be some voice for the voiceless'

Dandy is living with his 29-year-old son in Woonsocket and receiving treatment at Community Care Alliance as part of his release plan.

He takes a bus to Providence five days a week to help out his friends at Mathewson Street church, such as Clinker and Kevin Simon, the director of outreach and communication.

He has returned to his exercise regimen at the gym and healthy eating. He attends court dates at the direction of his new lawyer, Joshua Soares. He hopes his case will get dismissed.

He is thankful for all his supporters’ helping hands through the years and wonders about others who don’t have such backing.

“If you don’t have someone fighting for you, you’re in trouble,” Dandy said during an interview at Mathewson Street church just before Christmas. “There has to be some voice for the voiceless.”

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: Woonsocket man's case highlights shadowy and secretive competency court