Worcester Art Museum spotlights masterpiece portraits from London gallery

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

WORCESTER — A beautiful 1864 portrait of renowned English actress Ellen Terry is one of the most visitor-requested paintings in London’s National Portrait Gallery, but now you don’t have to travel so far to see it.

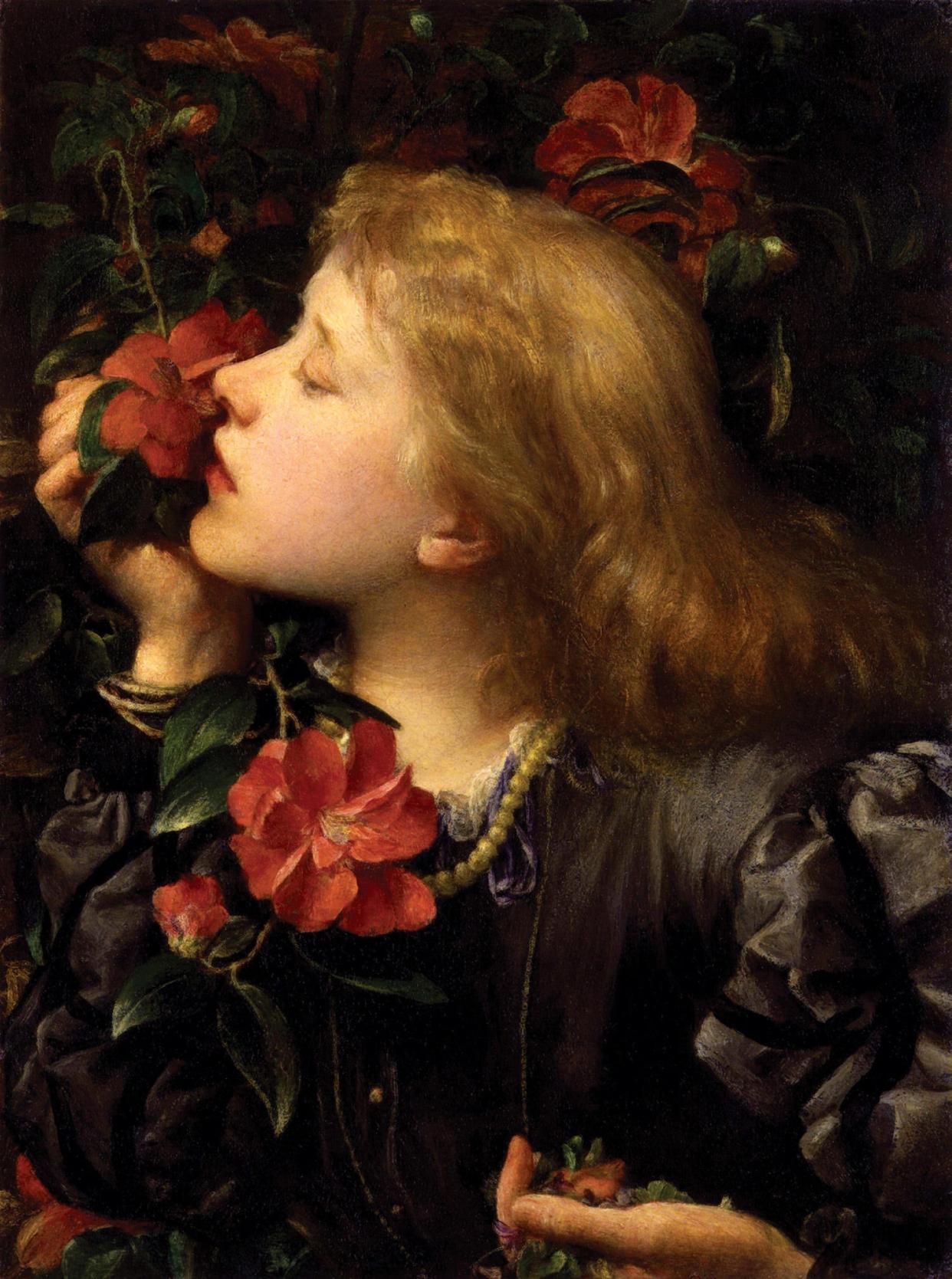

The delicate and sensuous painting by George Frederic Watts of the young Terry smelling a camellia flower is among masterpieces in “Love Stories from the National Portrait Gallery, London,” an exhibition that opened recently at Worcester Art Museum. The show, which includes works by such noted painters as Sir Joshua Reynolds, David Hockney, and Angelica Kauffmann among many others, runs through March 13.

$1 for 6 months:: Introductory telegram.com offer for new subscribers

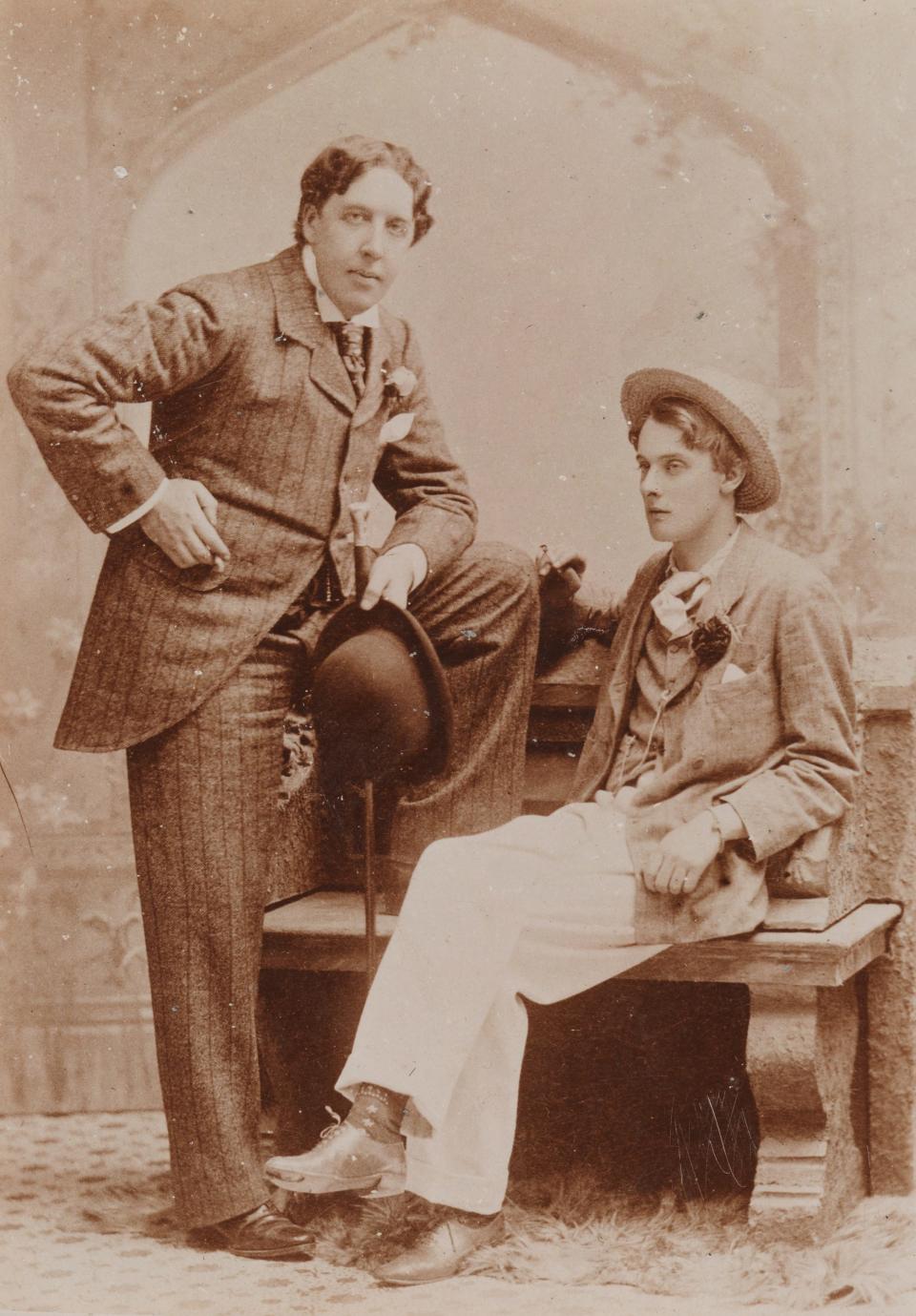

The love stories of the title include works that portray actual couples from 16th century romantic relationships to popular modern parings like Prince Harry and Meghan Markle. The show also includes portraits that deftly convey the bond between painter and sitter – mostly men painting women, but also women painting men, women portraying themselves, as in an affecting self-portrait by Bloomsbury painter Dora Carrington, and men painting men — or photographing them as in the striking images by Welsh photographer Angus McBean of his muse, Berto Pasuka, a Jamaica-born dancer who ignored his family’s wish that he become a dentist, studied ballet instead, and started the first all-Black ballet troupe in Europe in the 1940s.

More: Faces of love: Worcester Art Museum features works from National Portrait Gallery, London

Walking through the gallery, right away you can pick up on the show’s premise — that love and desire are foundational components of portraiture. The thematically organized exhibition looks at a variety of ways that love is artistically expressed but is based on the very traditional idea of the artist and the muse, most often that of a male artist trying to capture this obsession with his female muse.

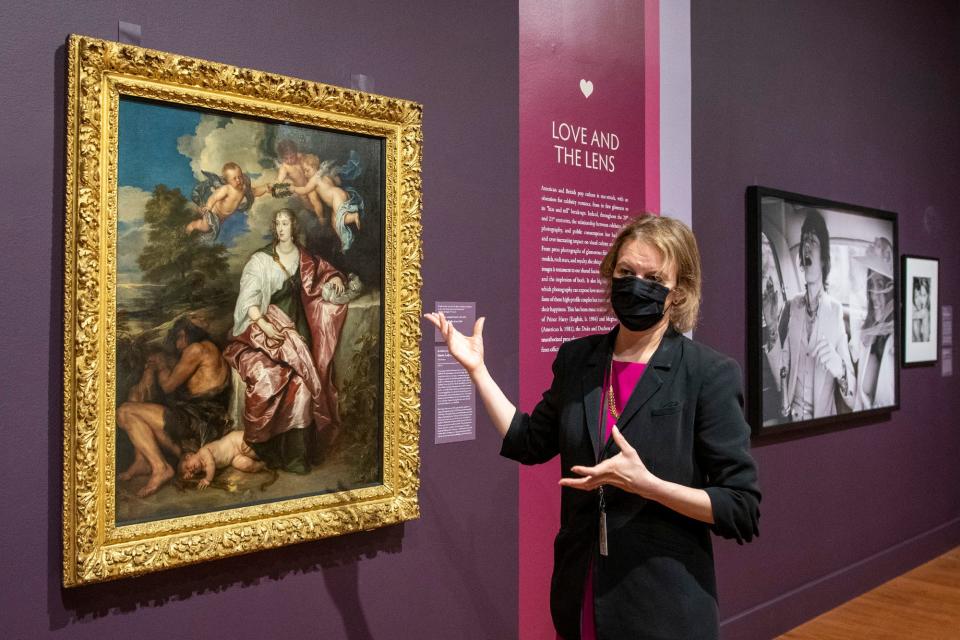

A gorgeous portrait of the Duchess of Cleveland with her infant son (circa 1664) by Sir Peter Lely, who was a Dutch artist at the English court, is an example of some of the genre’s rootedness in romantic impulse. Lely was so taken with the Duchess that other women he painted often shared a likeness to her that didn’t go unnoticed by the courtly observers.

“The contemporary critics talked about how, basically, every woman that Lely paints kind of looks like the Duchess of Cleveland,” Claire Whitner, WAM’s James A. Welu Curator of European Art, said during a recent tour of the show. “They saw a little bit of her face in all of those portraits.”

Not only was the Duchess a muse for Lely, but she was also the favorite mistress of King Charles II, making the paintings Madonna and Child-style composition particularly audacious. “It’s actually a portrait of the king's mistress and their illegitimate child so that was particularly sassy for a Protestant nation at the time,” Whitner said. “This is really meant for the inner circles of the royal family. That Court was known for being particularly licentious, but it was still a pretty bold statement to depict.”

In the famous G.F. Watts painting of Terry with a camellia bloom at her nose, classic muse obsession runs into staid mid-19th century social mores. Watts has fallen deeply in love with Terry even though he is 30 years her senior and sees himself as a man of moral eminence whose mission is to save her from the decadent life of the stage.

In “Choosing,” the flowers have an allegorical value to them. Terry is smelling a red camellia, a flower that is beautiful yet scentless, meant to represent the decadent vacancy of the stage, Whitner said. In her other hand, she’s holding violets, a symbol of purity and authenticity. “Hs's thinking that, by marrying him, she's choosing the sort of pure truer thing rather than the vanity of the stage,” she said.

Terry did end up marrying Watts, but the union lasts barely a year. “At the time, if you were a professional woman and you got married, you’d have to give up your profession,” Whitner said. Watts had thought he would sort of tame her wild spirit, but that did do not happen and after they separate, Terry went on to become one of the leading actresses of her time.

It was a three-year renovation project at the National Portrait Gallery that led to a decision to allow works of this exceptional caliber to make the trip across the pond for a Worcester showing. The museum will remain closed until spring 2023 while the extensive renovations and reimagining of its galleries continue.

Worcester Art Museum had begun building a relationship with the National Portrait Gallery when WAM lent its iconic double portrait of Gainsborough's Daughters to their “Gainsborough’s Family Album” show, which ran from November 2018 to February 2019.

“I think that's why they came to us to see if we were interested in this exhibition,” Whitner said. “It was a really unique, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity because that collection is likely not going to travel again in my lifetime.”

Another reason likely was because WAM has an excellent - though not necessarily large - collection of British portraits from the 18th and early 19th century, the golden age of British portraiture.

“I thought it would be interesting to kind of build that out, to think more broadly on ‘What is British portraiture in the larger spectrum of things? What is it now? What does it mean to even have a portraiture gallery now in the 21st century?’” she said.

One answer to those questions is that portraiture is a genre where you have two people responding to each other in highly varied ways. The fascinating results of this sort of dialogue can be seen throughout the 500 years of portrait making covered in the exhibition.

“There's always a negotiation between the artists and the sitters,” Whitner said. “The sitters have certain expectations, the artist has certain desires and then there’s trying to figure out how you square that when in so many cases those are conflicting desires, especially from an artist who doesn't necessarily like the person that they're portraying.”

In the WAM exhibition’s case, the theme was love and the ways portraitists crystallize that immaterial aspect in the moment. “One thing the exhibition looks at is ‘How do you move beyond a particular moment into something that speaks more broadly to a relationship that's lasted a lifetime?’ And I think that's something we care very much about in the 21st century as well,” Whitner said.

That ephemeral-yet-transcendent quality is particularly hard to convey in a static image, which all the works in the show are with one exception: a video portrait of English footballer David Beckham sleeping soundly in a Spanish hotel after a Real Madrid training session.

The video by Sam Taylor-Johnson (known as Sam Taylor-Wood when it was made in 2002) seems much like a static portrait at first glance. Then, after a moment, it moves — ever so slightly, as the sleeper unconsciously makes minor adjustments. There is no fitful tossing and turning here, however, but rather a soothing portrait of chiseled, shirtless exhaustion in peaceful repose.

This article originally appeared on Telegram & Gazette: Worcester Art Museum spotlights masterpiece portraits from London gallery