Word from the Smokies: Henry Lix's legacy as founder of park’s natural history association

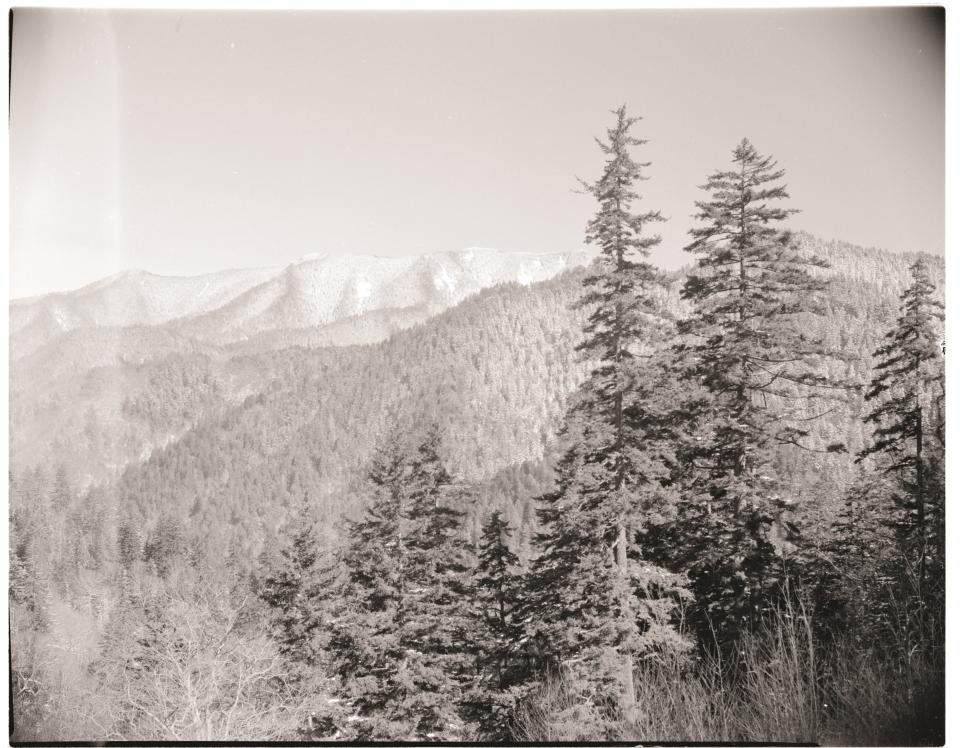

Seventy years ago, a friendly and generous man with boundless curiosity founded the park partner organization that today is known as Great Smoky Mountains Association. As GSMA celebrates seven decades of educational service and now nearly $50 million in support to Great Smoky Mountains National Park, we reflect on this important pioneer and how he shaped the ongoing collaboration between parks and their nonprofit supporting agencies.

In fall 1951, Henry Lix arrived in the Smokies as the park’s second full-time naturalist, tasked with expanding the scope of educational activities and amplifying their benefits for visitors. With an easygoing personality, wide-ranging interests, and a master’s degree in geology from the University of Missouri, he set out to create a natural history association that would produce engaging educational material and create revenue for new projects in what would become America’s most-visited national park.

Lix was, in many ways, an ideal person to set up the Great Smoky Mountains Natural History Association (later renamed Great Smoky Mountains Association to take in cultural as well as natural history). He had already started an association in Hot Springs National Park in Arkansas in 1935, where he worked as a park policeman, catalogued plant and animal species, and honed his specialty, geology.

After a few years in Hot Springs, Lix obtained a postgraduate fellowship at Yale University. There he became friends with both Henry Graves, founder and dean of the Yale School of Forestry, and Gifford Pinchot, cofounder of the National Forest Service. Conversations with these men and other thought leaders gave Lix an appreciation for master planning, political influence, and how budgets dictated priorities.

In 1941, Lix accepted a new naturalist position at Mammoth Cave in Kentucky. He served in the Army from 1942 until 1946, and upon his discharge in 1947, eagerly returned to Mammoth Cave. There, he oversaw interpretive plans, museum plans, and establishment of another natural history association.

Like Hot Springs, Mammoth Cave had a rich tradition of legends and tall tales, and Lix guided the new association toward producing material that separated fact from fiction. He was meticulous in his research, writing and cataloging information that future staff found valuable for decades, including a safety guide for many emergency scenarios that might occur in the caves. Lix felt the distinguishing work of NPS interpretation was, as he put it, to “move parks beyond picnic places” and teach visitors in a compelling way about America’s remarkable landscapes.

His first project in the Smokies was to research and write “A Short History of GSMNP,” a succinct overview that combined scientific understanding and cultural history. Prior to his arrival, interpretive work had focused on the landscape’s ‘return to nature’ and its diverse biology. Lix’s research also considered the area’s vibrant human history and informed the broader interpretive work of the Great Smoky Mountains Natural History Association, formally established in March 1953.

The founding board of directors included Lix, as well as park leadership like Chief Naturalist Arthur Stupka and Superintendent Edward Hummel. Hummel, who oversaw much of the Smokies’s Mission 66 development, was supportive of the ideas Lix had for the association and gave him freedom to grow and develop its work.

More: Word from the Smokies: Partners help meet needs of Great Smoky Mountains park, visitors

More: Word from the Smokies: Roamin’ with Wiley Oakley, legendary mountain guide

Hummel’s predecessor, John Preston, likely played a significant behind-the-scenes role as well. He had overseen the growth of the Mount Rainier Natural History Association in Washington for 10 years before coming to the Smokies (arriving, like Lix, in 1951), and he too had firsthand knowledge of an association’s value for a national park. The Mount Rainier association lent Lix $100 to cover startup costs, suggesting Smokies’ budget shortfalls might otherwise have created delays.

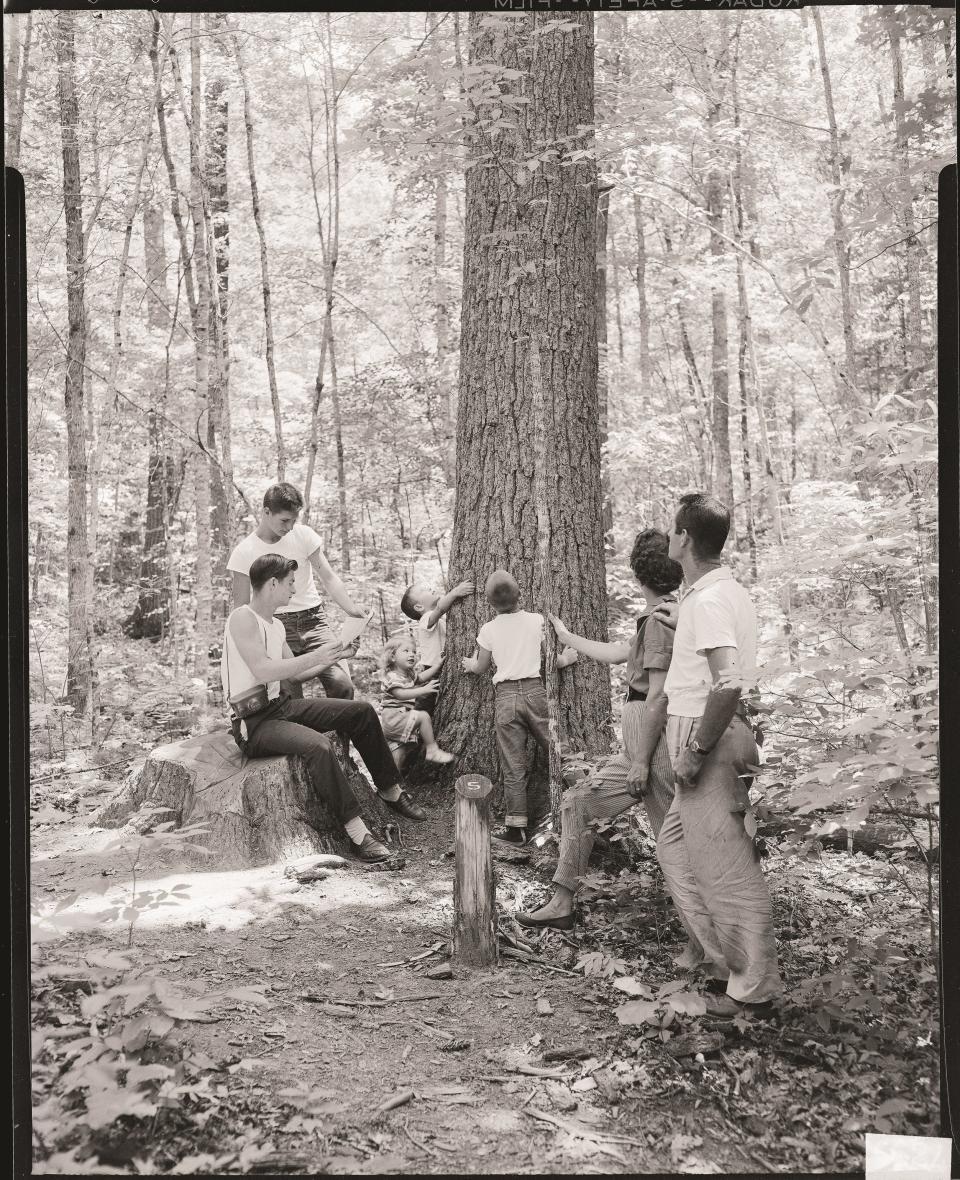

Lix strove to create a variety of compelling, fact-based narratives about the Smokies, including self-guided hiking brochures that gave people access to information even if they couldn’t hike with a ranger or attend a talk. He also decided where the association’s products were sold; recognizing that Cades Cove would be hugely popular with visitors, he prioritized sales outlets for what is now the popular loop road. Visitor centers were also prime spots, and site-specific guides were available for free at popular trailheads.

As projects expanded, Lix outsourced book publishing to professional local printers. Pamphlets were usually free or 5 cents; books cost up to a few dollars. After Sugarlands Visitor Center opened in 1960, printing operations moved to the basement there; Lix had allotted space for association offices in his suggestions for the building layout.

The association quickly became profitable, raising nearly $90,000 in its first 10 years and contributing about $25,000 for new park projects. These ranged from preserving cabins and farming structures to expanding educational offerings, including sorghum milling demonstrations in Cades Cove and ‘living history’ programs in the decades to come. During Lix’s almost 15 years of shepherding the association’s work, it had no more than two employees and benefited greatly from his and other park staff’s time and expertise.

More: Word from the Smokies: George Ellison — too much and not enough

More: Word from the Smokies: Old wallet helps archivist dig into Cades Cove history

Great Smoky Mountains Association is now an independent nonprofit operating 11 visitor centers or visitor contact stations in and around the park with 80 to 100 employees depending on the season. It has 29,000 members and 140 business members, distributes 1.5 million pieces of free or inexpensive literature about the national park each year, brings in over $10 million in annual revenue, and has contributed more than $48 million in aid to the park since Lix drafted its founding documents in 1953. It contributes much-needed financial support for park projects, many of which are still beloved parts of visitor experiences.

Lix understood that a well-run association could enrich visitor experiences and generate an important source of income for park programs. His expertise gave what was then called the Great Smoky Mountains Natural History Association a strong foundation for growth, and he guided its development until his retirement in 1967.

Lix died in 1993, but GSMA’s commitment to explaining the remarkable attributes of the Smokies and enhancing visitor understanding remains true to his founding work. He would be proud of what the association has become, looking forward to its next 70 years.

An expanded version of this story appears in the spring 2023 issue of Smokies Life, a biannual publication that serves as the primary benefit for more than 29,000 members of Great Smoky Mountains Association. This version was edited for this column by Frances Figart. Learn more at SmokiesInformation.org.

Courtney and Vernon Lix are a father-daughter team. Vernon lives in Gatlinburg and has been photographing the Smokies for decades. His previous subjects for Smokies Life include Gregory Bald azaleas, the Clingmans Dome tower, and mountain winds. Courtney lives in Virginia and wrote "Frequently Asked Questions about Smoky Mountain Black Bears” and "Women of the Smokies.” They are proud to continue Henry Lix’s legacy of sharing important stories about the national park.

This article originally appeared on Asheville Citizen Times: Word from the Smokies: Henry Lix's legacy as founder of GSMA