Word from the Smokies: Photographer and parks shine a light on the magic of fireflies

Great Smoky Mountains National Park is home to large populations of synchronous fireflies, which create a magical spectacle that draws thousands of visitors each year. The park will host the annual synchronous firefly viewing opportunity at its popular Elkmont Campground June 3-10 this year, but there are many other places where this flashy courtship ritual can be seen in our region.

Only a handful of experts know more about where to find fireflies than Radim Schreiber.

Growing up in the Czech Republic, Schreiber did not experience fireflies as a child. But when he moved to the United States, his fascination with these tiny creatures became an obsession.

It all started with a vision of a firefly on a blade of grass in the light of a full moon.

More: How can you get a ticket to view Great Smoky Mountains synchronous fireflies this June?

► Word from the Smokies: Synchronous fireflies light up the night

► Word from the Smokies: Reducing artificial light at night can save thousands of park birds

“I had a vision for many years to take a photograph of a firefly but had no idea how to accomplish it,” he said. “I had to wait for advancements in the low-light capabilities of cutting-edge camera equipment before I was able to photograph fireflies. That technology finally came, and every summer since then I have photographed and recorded fireflies on video.”

In 2011, Schreiber had only been exploring firefly photography for a few years. He took a quick snapshot of a big dipper firefly (Photinus pyralis) with its unique amber glow. The image would win him notoriety as The Firefly Photographer when it won first place in both the National Wildlife Federation’s 41st annual photo contest and Smithsonian magazine’s eighth annual photo contest. A host of other such awards would follow.

Both synchronous and blue ghost fireflies can be seen in many of Schreiber’s spectacular images shot in the Smokies’ Elkmont and in other locales such as Rocky Fork State Park in Flag Pond, Tennessee. Between late May and mid-June, beginning around 30 minutes after sunset, males of both species display, sometimes interspersed. Synchronous give 5-11 yellow flashes followed by a 6- to 9-second pause, while blue ghosts stay on continuously for up to a minute, hovering close to the ground.

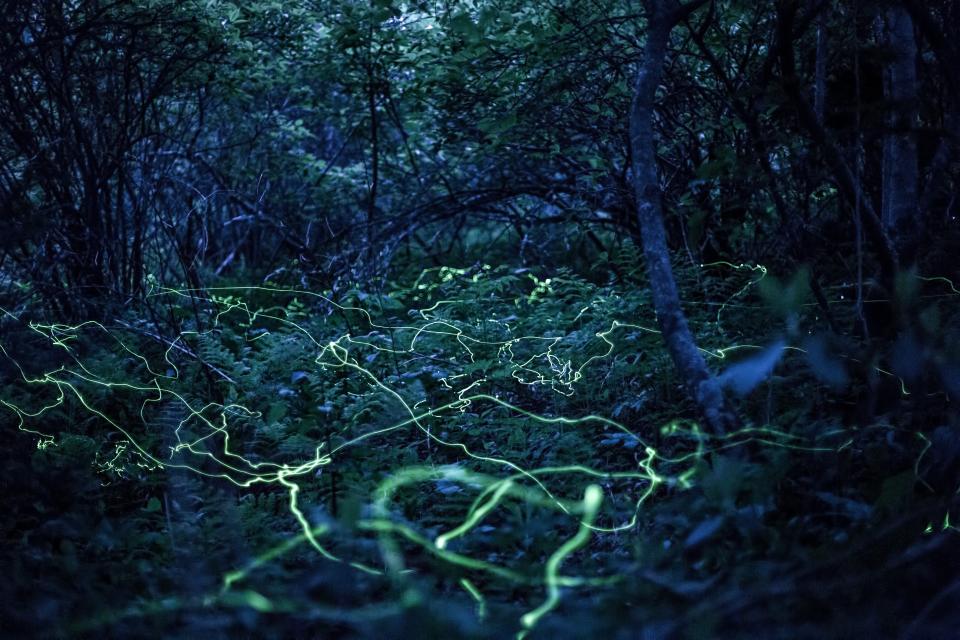

Schreiber’s work is featured in the new 2023 GSMNP calendar, which just became available. Each page showcases a different image, along with quotes from Schreiber and natural history notes about fireflies. The September image shows an amazing 49.6-second exposure of the eerie blue ghosts.

“Something inspired me to climb to an overlook, despite darkness creeping slowly in,” Schreiber recalls. “On the way up, I froze in my tracks when I saw a large black bear on the path. He saw me and quietly disappeared in the shady growth.”

► Word from the Smokies: Wait, don’t kill It! Spiders protect us from disease

► Word from the Smokies: Assassin bugs discovered to exist in the Smokies

Cautiously, he continued his ascent and reached the overlook near dark.

“I quickly started back while I could still see the path and slowed down where I had seen the bear,” Schreiber said. “Suddenly I saw little lights like fairies quietly floating just above ferns. I started to photograph them and got this single exposure. I have a feeling the bear knew where I was the whole time.”

There are at least 19 species of firefly just in Great Smoky Mountains National Park alone, and many of these illuminate the night skies throughout the Appalachian region. Right now, I am seeing the spring treetop flasher (Pyractomena borealis) in my backyard in Flag Pond, Tennessee, just 40 minutes north of Asheville. The earliest flashing species to emerge, these beetles produce yellowish lights up in the tops of trees about 45-90 minutes after dark as the males attempt to attract females with a flash about once every two to four seconds.

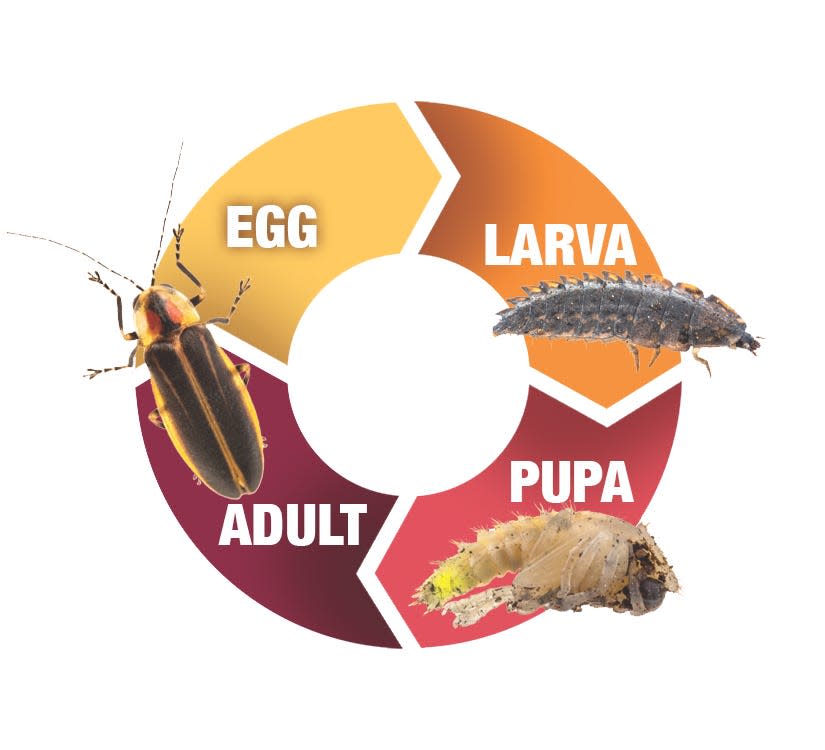

Like other insects, fireflies need high-quality habitat in order to survive and complete their lifecycle. The ground-dwelling life stages (eggs, larvae, pupae, and flightless females of some species) are particularly vulnerable and need a moist, undisturbed layer of leaf litter for shelter. Urban development, changes in land use, changes in water availability, and the reduction in water quality can all have dramatic, negative effects on fireflies.

Artificial light at night (ALAN), which includes both direct lighting and the indirect glow from urban lighting, can also negatively affect many firefly species. ALAN disrupts the courtship display of certain species, causing changes in behavior and reducing their populations.

You can help fireflies in your own backyard by following these four simple steps.

Reduce artificial lighting. Turn off outdoor lighting when you’re not using it, particularly during the summer months when fireflies depend on darkness the most for their courtship displays.

► Word from the Smokies: GIS makes it simpler to map a complex park

More: Word from the Smokies: Plant life makes a comeback after 2016 wildfires

Eliminate pesticides. This will help to protect fireflies, pollinators, and lots of other invertebrates, as well as the animals that feed on them, such as birds, bats, and other wildlife.

Establish good firefly habitat. Grassy lawns may look nice, but they aren’t good habitat for most native species, so consider leaving a patch of yard to grow un-mowed. Let the area lie undisturbed, leaving leaf litter and dead vegetation in place.

Plant native plant species. This will help fireflies, bees, butterflies, and other pollinating insects as well as birds, and dramatically increase the biodiversity of your yard!

“Fireflies are an important part of their environment, playing an integral role in the local food web as both predators and prey,” said Will Kuhn, a firefly expert and the director of science and research with Discover Life in America. “When imagining a firefly, we usually think of a typical winged black, yellow, and orange firefly adult, but in fact a firefly spends most of its life as an armadillo-like larva, crawling through leaf litter feeding on soft-bodied invertebrates such as snails, slugs, and earthworms.”

Kuhn says fireflies have many predators, such as frogs, toads, spiders, bats, birds, and even other fireflies! However, some fireflies have chemicals in their blood that make them distasteful to would-be predators.

The public may apply for GSMNP’s June 3-10 synchronous firefly viewing opportunity at Elkmont by entering a lottery for a vehicle pass by searching for Great Smoky Mountains Firefly Viewing Lottery at recreation.gov. The lottery opened for vehicle pass applications April 29 and goes through 10 a.m. May 3.

If you enjoy the images seen here, you can take all of them home in the 2023 park calendar featuring firefly photography by Radim Schreiber and written, designed, published, and sold by Great Smoky Mountains Association at smokiesinformation.org. Schreiber’s book, “Firefly Experience,” is available in the GSMA-run visitor center bookstores and online at smokiesinformation.org.

If you would like to learn more about fireflies, attend a free talk by firefly scientist Will Kuhn at the Town Hall at 211 N. Main St. in Erwin, Tennessee, at 4 p.m. May 14. Kuhn’s presentation will be hosted by the Friends of Rocky Fork State Park, another park that has both synchronous and blue ghost fireflies. Rocky Fork’s lottery for its annual firefly programs will begin May 9 and close midnight May 14. Learn more at tnstateparks.com or email Park Manager Tim Pharis at tim.pharis@tn.gov.

Frances Figart lives near Rocky Fork State Park, is the editor of “Smokies Life” journal and the Creative Services Director for the 29,000-member Great Smoky Mountains Association, an educational nonprofit partner of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Reach her at frances@gsmassoc.org.

This article originally appeared on Asheville Citizen Times: Word from the Smokies: The magic of the firefly viewing opportunity