Worker's Home transformed to show Black family's struggles and triumphs in 1950s

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

SOUTH BEND — In a tiny alcove, just off of the dining room, a half-repaired 1946 RCA Kit TV sits where the man of the house spent his time repairing televisions — one of two side gigs to his job at the Studebaker car plant.

His musical instruments sit below that, a coronet and tambourine. As a Black man, he normally wouldn’t have been allowed into the local musicians union. World War II gave him a break. White musicians were off to war, so unions opened their doors. But nightclubs didn't want to book Black artists for too many nights because they didn’t want to attract Black audiences.

Stephanie McCune-Bell, The History Museum’s director of education, took The Tribune on a tour of a house here on its campus, with artifacts that tell the struggles and perseverance of one family’s life. For nearly 30 years, this was Dom Robotnika, the 1930s-era Polish Worker’s Home. On Nov. 9, it will reopen as the 1950s African American Worker’s Home.

City trailblazer: Music was saving grace for first Black in South Bend Symphony

That date dovetails with South Bend Civic Theatre’s premiere Nov. 10 of “Better Homes: The Play,” based on the book by local author Gabrielle Robinson about Black Studebaker workers who secretly met in 1950 to build family homes away from the slums where city redlining practices forced them to live.

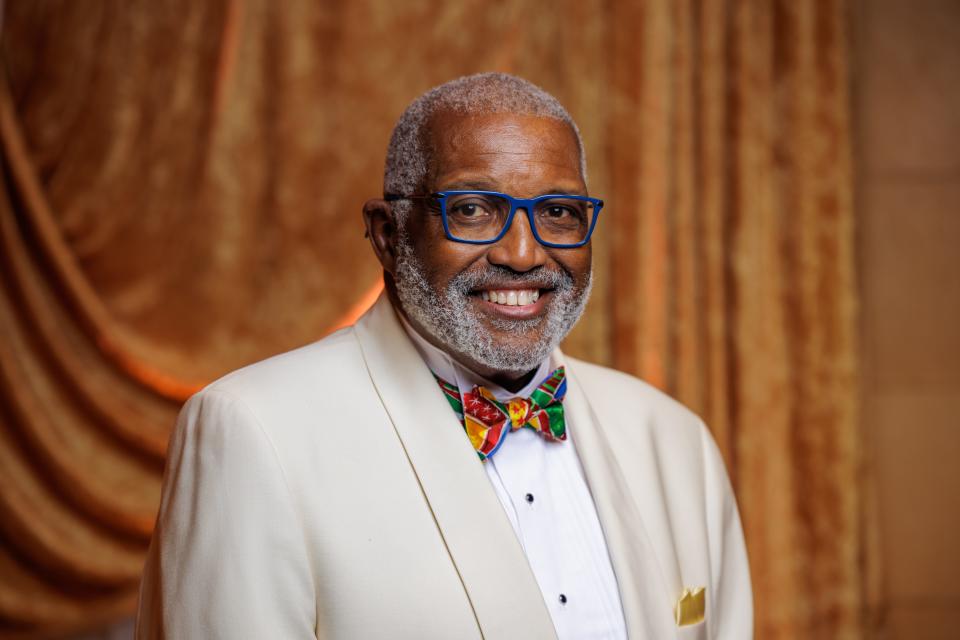

“It’s a history lesson folks don’t want to talk about,” Marvin Curtis, who serves on The History Museum’s board, said. “It’s a shameful part of our history. But when we talk about these things, folks see we don’t need to go backwards.”

Through those struggles, he said, visitors will see that “people got these homes because they worked for them.”

Museum docents will tell visitors about the middle-class working family living in this house, a fictional family but one that McCune-Bell said is pieced together from the stories of real, local residents. Staff listened to recorded accounts at the IU South Bend Civil Rights Heritage Center and interviewed local residents for more oral histories of African Americans about life in the 1950s.

Those stories helped to craft the home’s totally new interior, its items and its narrative.

It focuses on the 1950s, McCune-Bell said, because so much was going on — the post-war consumer society, the space race and the advent of TV, which “propelled the Civil Rights Movement” that was taking off on a national level.

In the living room, visitors will find a 1950s Motorola TV and, thanks to a hidden digital TV that replaced the original guts, the glass screen will show news clips of the era, from commercials to news of desegregation and the Little Rock Nine.

On a nearby table, there’s an Ebony magazine cover story in February 1950 about the first Black students at the University of Notre Dame, plus a redlining map of South Bend-Mishawaka.

Next to that, docents can pick up a reproduction of “The Green Book.” The little 1952 guidebook listed where Blacks could safely travel and recreate across the U.S. One such spot was Paradise Lake in Vandalia, once home to a thriving Black resort, now gone, that closed when civil rights laws allowed Blacks to travel more freely. There’s a photo of it in the house because the father kept a motorboat on the lake.

From the Outdoor Adventures archives: Bike ride through Underground Railroad history

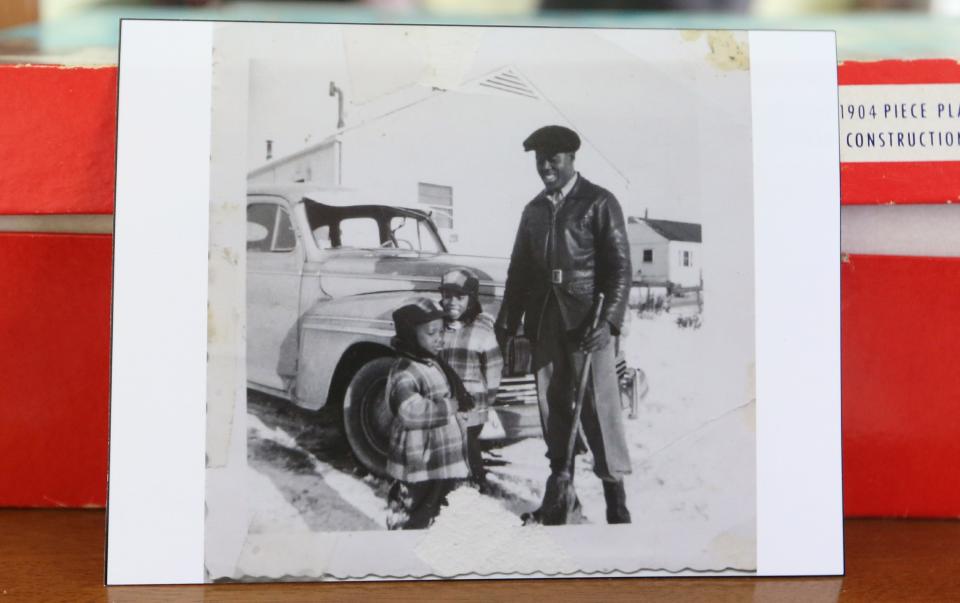

This house also represents the Great Migration that, by 1950, had drawn more than 8,000 Blacks to this area from the South to pursue the promise of better jobs and freedom from racism and Jim Crow laws. That influx spurred competition for work that translated into racism here, or in Curtis’ words, ”trading one form of slavery for another” because, for example, Black people had to enter public buildings through back doors.

Physical transformation of the Worker’s Home began as it closed after Labor Day. A local African American contractor stripped the wallpaper and ceiling paper throughout the house and painted the plaster walls in shades of dark blue, yellow and white that folks seemed to use in the 1950s. In the kitchen, he replaced the red linseed oil floor with linoleum, bearing a black-and-white checker pattern to match the era, so that it contrasts with a red metal-and-Formica table.

Change had been a long time coming

Executive Director Brian Harding has been serving the museum for about 30 years, first as a volunteer and later as a board member. He was familiar with the African American artifacts and local family heritage that the late John Charles Bryant had added to its displays.

But after Harding was hired as its director three years ago, he recalled, “There was a group of African Americans who told me point-blank that there was very little reason for African Americans to visit.”

“I was shocked,” Harding said. “We have not done enough.”

The house posed an opportunity. It was built in the 1870s and was moved in 1907 to the property of J.D. Oliver, owner of the Oliver Chilled Plow Works. A series of the Oliver family's domestic staff lived in it until the mid-1980s. The house moved to its current site in 1992, where the museum opened it as the Worker’s Home in 1994.

The original idea was to change the ethnicity, decor and story of the house every seven years, give or take. But that never happened. Harding said it was largely because of the lack of resources that it would require of the nonprofit to make the changes.

Curtis was among those advocates for better representing Blacks, who, he pointed out, now make up 24% of South Bend’s population. He chairs the museum board’s special committee on diversity, equity and inclusion and plays the same role on the board of the South Bend Symphony Orchestra.

The museum formed an advisory committee of more than 15 Black and other community leaders to reimagine the house. And when Curtis asked Tina Patton to chair the committee a year ago, she recalled: “I had not heard of this house. When this project is done, I hope the community never says that.”

Together, they reconceptualized the house and helped to source its contents, some of which came from local residents.

They also raised money to make the change, bringing in at least $56,000, which surpassed their goal of $50,000, Curtis said. Surplus money raised, he noted, could support marketing and the future evolution of the house. Perhaps in a couple of years, he said, the house could be tweaked to reflect a Black family in the 1960s.

Further ahead, possibly in 2030, Harding said, the next iteration would be a Latino home.

“We’re looking at the largest numbers of people who might be interested,” he said, hoping it would likewise engage volunteers and visitors.

But, in the next immediate step to tell more of the local Black story, Harding said, the museum will expand the “Free Life” exhibit on the museum’s lower level. A display there, which hasn’t changed since 1994, focuses on the Underground Railroad. It’s a section of the Voyages Gallery, which, Harding said, has plenty of room to add more stories of local African Americans. The museum, with help from its advisors, will envision that space in the coming year, hoping to complete it in late 2024.

In tandem with 'Better Homes' play

The mother in the Worker’s Home graduated from the historically Black Fisk University and moved to South Bend while her husband served in the Navy. In 1950, as the script goes, she became the first Black teacher in South Bend, teaching at the former Linden Elementary School. A photo in the dining room shows Peggy Flowers, one of the city’s first Black teachers, all of whom were restricted to teaching at Linden.

Born in 1951, Curtis grew up in Chicago, where, he said, his parents didn’t talk much about segregation and where the larger Black community softened the discriminatory effects of redlining. People in South Bend, as a smaller city, felt those effects more, and yet, he said, “I see such pride in the people that lived here.”

Robinson, who authored the book “Better Homes of South Bend: An American Story of Courage,” advised the house project with historical background, but she also provided some photos from her research.

The play had already been in the works for a few years. She said it will serve a nice complement to the house because the lead character, a woman, imparts the “visceral” emotions that Blacks bore with the so-called “Migration blues.”

After the play’s run Nov. 10 to 19 at South Bend Civic, it will be performed in museum’s auditorium — four times for hundreds of school students and then one last time for the public at 7 p.m. Nov. 30, preceded by tours of the house.

Seeing 'hope for a brighter future'

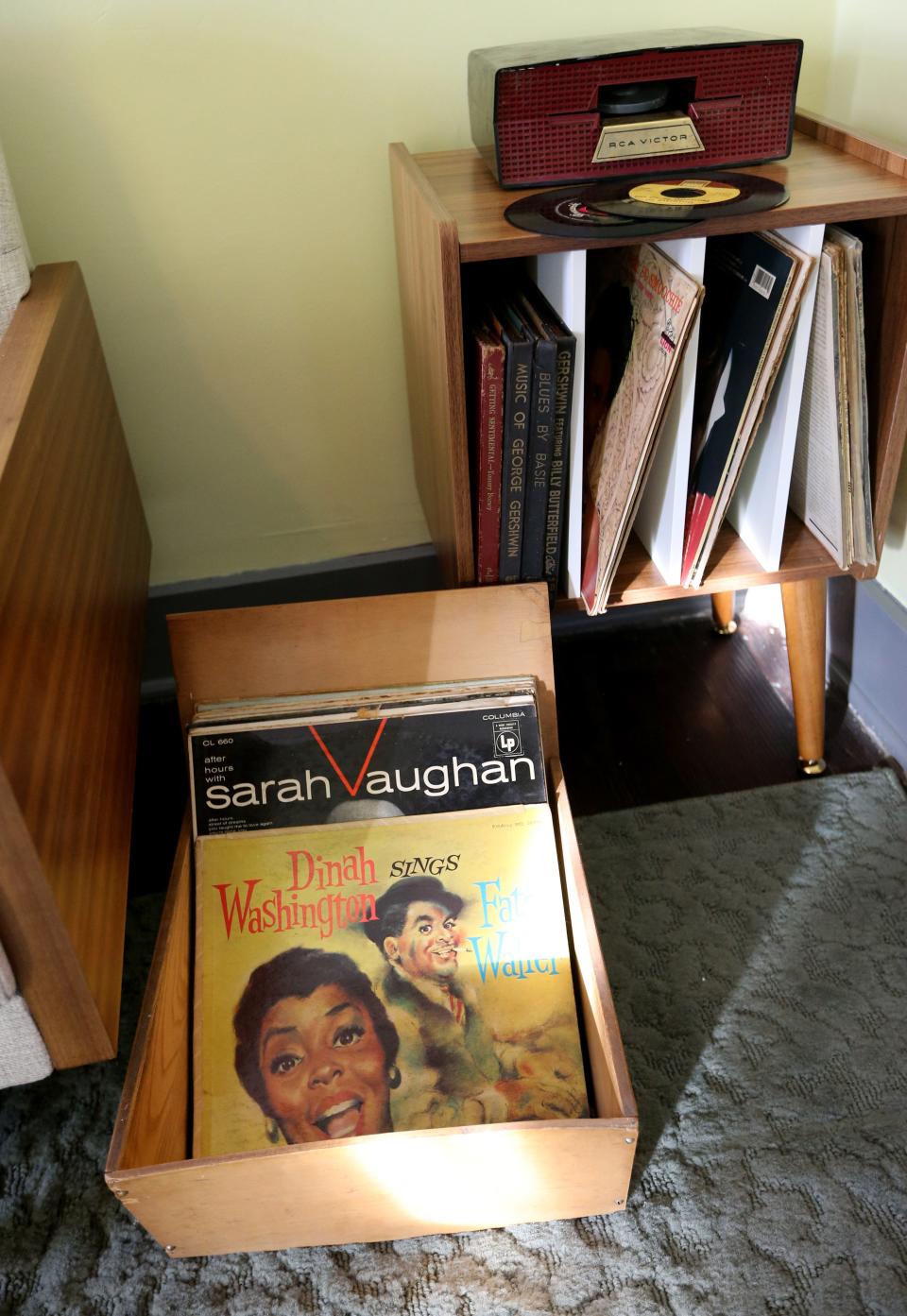

This is a small, comfortable home with a large, wooden 1945-46 Crosley hi-fi radio, plus a turntable from 1958. The father’s side jobs, McCune-Bell pointed out, “was the first seed planted for generational wealth.”

"Generational wealth … does begin with home ownership,” said Patton, who works at Indiana Trust Wealth Management as director of nonprofit and foundation engagement.

She sees that as president of Cross Community, a community development corporation that’s building affordable housing on South Bend’s northwest side.

But Patton feels a lot of people aren’t aware of the many barriers that African Americans once had with trying to afford and own a home that they “could be proud of.”

Her own parents had moved to South Bend in the 1950s and raised 12 kids. To make that happen, her father worked a side job as a band leader. They persevered thanks to their faith, she said, as their time in church would nourish and support their spirits through their trials.

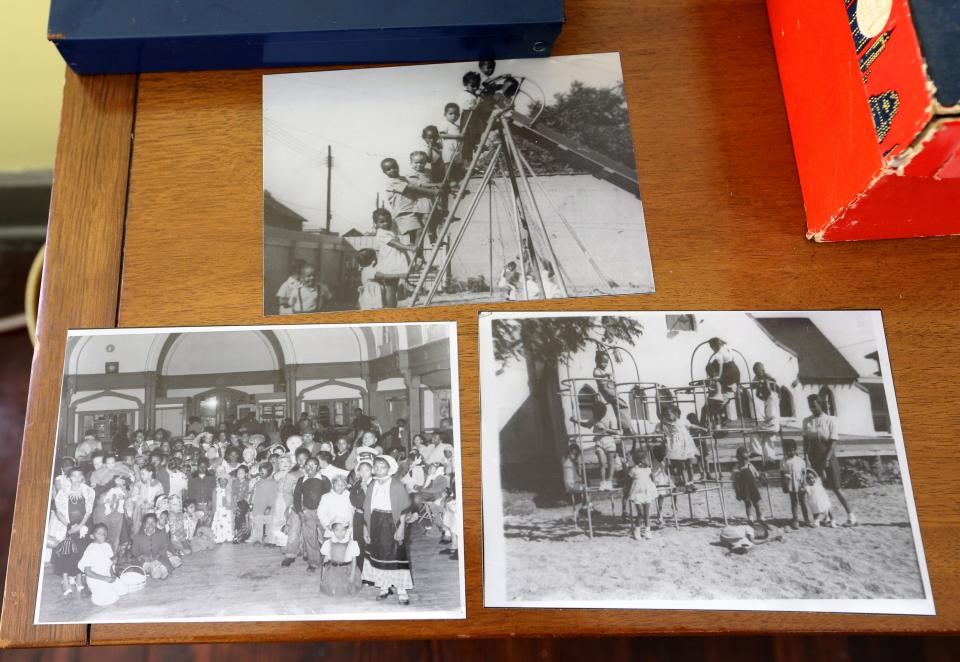

The child’s bedroom has toys of the time, such as Tinkertoys and an Elgo set of skyscraper building blocks. There are also photos of the popular Hering House, where Black kids recreated when places such as the YMCA, YWCA and city parks were exclusively for whites.

Patton said kids here can "see pieces of themselves and be able to relate.”

“We don’t know the struggles they (today’s kids) are going through,” Patton said. By touring the house, she hopes they see: “There’s always hope for a brighter future. Yes, you can make it out of what you’re going through.”

To visit the Worker's Home

The History Museum, 897 Thomas St., South Bend, opens its 1950s African American Worker’s Home on Nov. 9. The house can be seen through tours. As in the past, tours will be included with tours of the Oliver Mansion at 1 and 2 p.m. daily, all part of the price of museum admission, which is $11-$7. Museum hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Mondays through Saturdays and noon to 5 p.m. Sundays. For more information, call 574-235-9664 or visit www.historymuseumsb.org.

South Bend Tribune reporter Joseph Dits can be reached at 574-235-6158 or jdits@sbtinfo.com.

This article originally appeared on South Bend Tribune: The History Museum Worker's Home revamped to 1950s African American