The World’s Most Beautiful Libraries: Real Gabinete Português de Leitura

I can’t remember the title nor an iota of the content, but I vividly recall furtively pulling a random green leather-bound book from the middle of the shelf as if, like a magician with a playing card’s suit, the library just might guess the book’s contents.

I settled under the glossy and cracked gaze of Gilbert Stuart portraits and spent the afternoon reading this dense and probably outdated text. I was roughly 12 and living out a library fantasy at one of America’s most storied and beautiful Palladian edifices—Redwood Library in Newport, Rhode Island.

The air was suffused with plaster and paint that hadn’t ever seemed to dry (a common New England affliction), and the decay of dead trees covered in the long forgotten, if ever remembered, words of dead men and women.

Heaven.

I’d always had a romantic literary fantasy of swimming in books and devouring them one by one, day by day, in a beautiful library like this. My aunt even got me a membership. However, I must admit, I don’t think I’ve stepped foot in Redwood since that day. (Instead, I could always be found sweaty and blissful hunched over on those clover leaf-shaped stools reading some fantasy or young adult novel that grabbed my eye at the public library after basketball practice and in between games at the Newport Rec Center just across the parking lot.)

But my obsession with libraries of great beauty and their collections has never waned. A magnificent library is a space that combines two forces (beauty and knowledge) to truly inspire awe in a way few places can. Two other edifices that come to mind are houses of worship (beauty and faith) and government buildings (beauty and power). Indeed, in any city anywhere, libraries, churches, and government buildings are usually the most visited sights.

It’s why I’m ecstatic we’re going to give our readers a rich dive with a new series: The World’s Most Beautiful Libraries. There are plenty of listicles around the internet, but once a month we’re going to give you a full look at each of these iconic places. Some will be grand old things à la Beauty & the Beast, and some sleek and modern. Some you may know, others will have escaped your notice. Our hope, though, is to give these places that hold so many of our shared stories, well, a better story of their own. And there are few libraries in the world (or spaces period) more beautiful than the Real Gabinete Português de Leitura in the center of Rio de Janeiro.

The front facade of the library.

In the heart of old Rio, across from a small plaza used as a parking lot, sits a charming but restrained Neo-Manueline building one could mistake for a neighborhood church or school. Most of its facade is smooth limestone, and unlike many of its neighbors, free from graffiti. The only ornamentation hinting at the splendor inside can be found on finials, around the gothic windows and doorways, and along the roofline. In relatively demure lettering across the top of the center of the building is written: Real Gabinete Portuguez de Leitura.

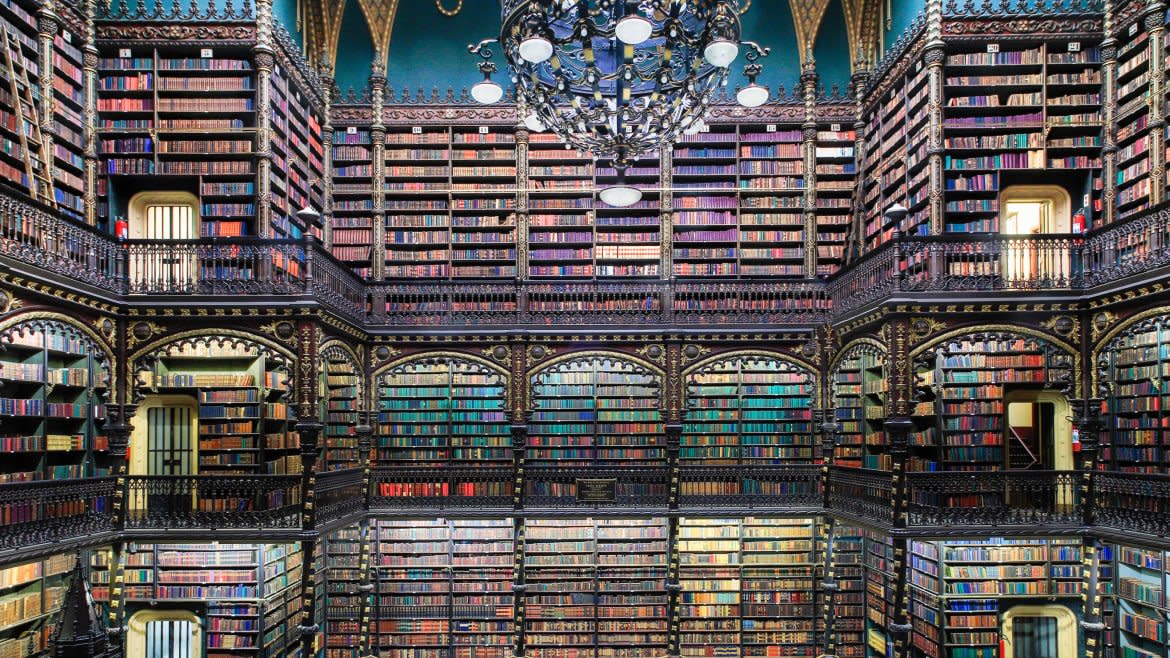

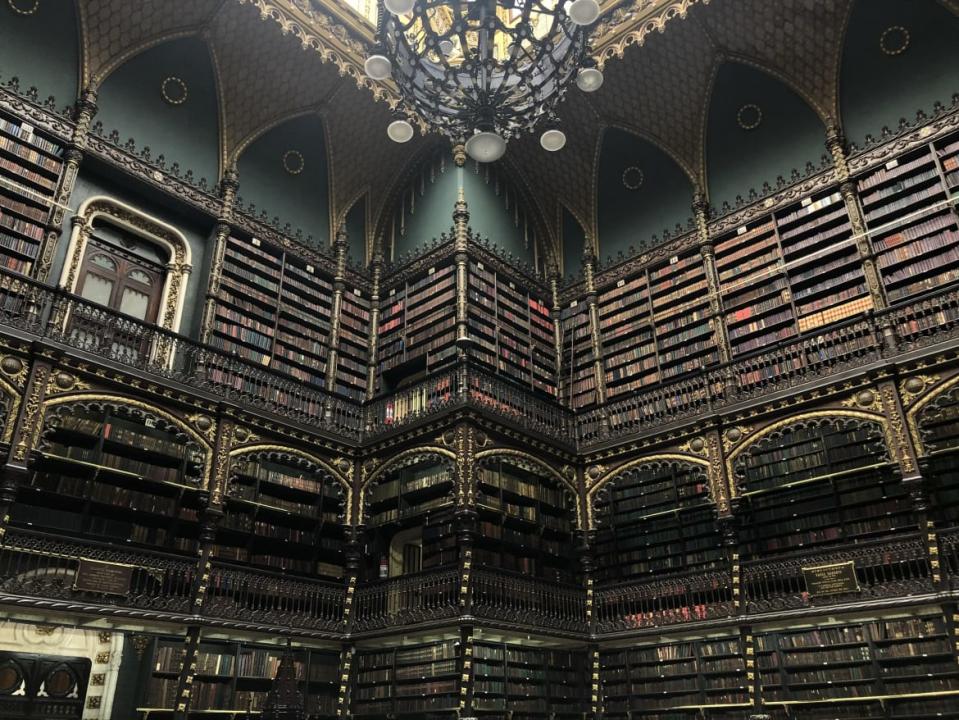

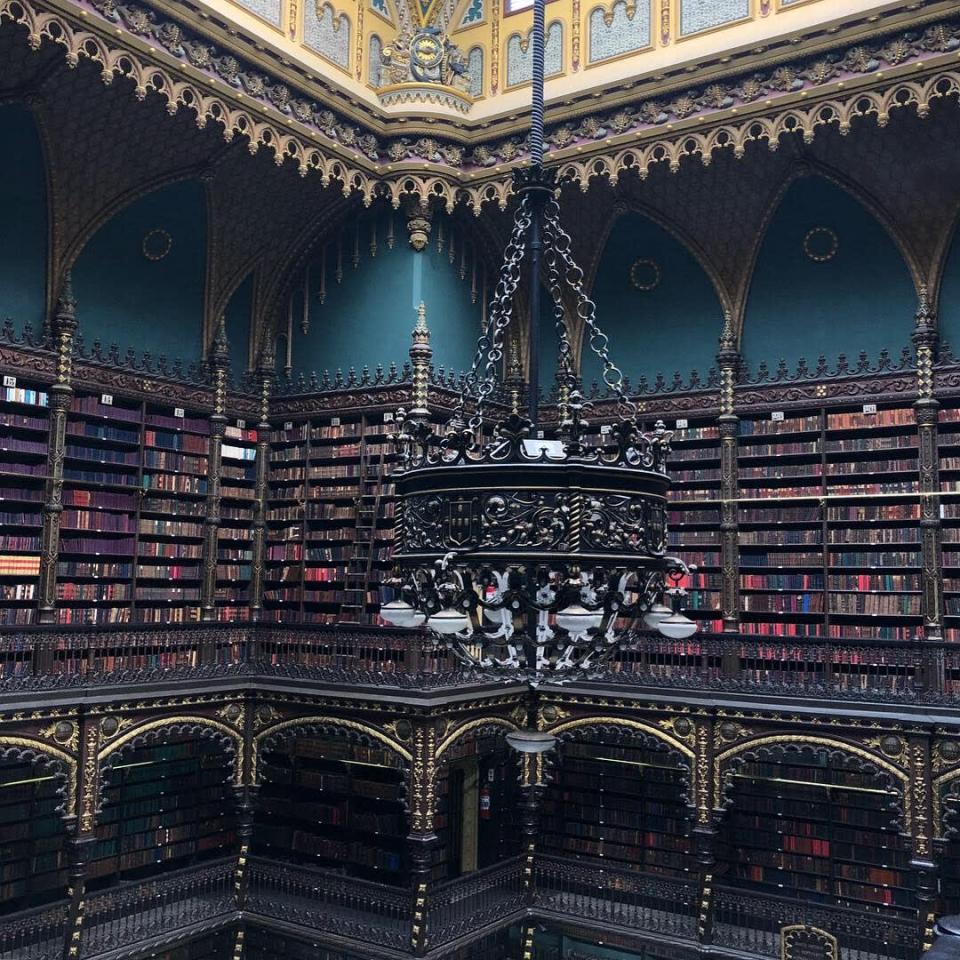

But inside, after passing under a lunette of elegant curling iron vines and through a vestibule floored with sumptuous tiles, one enters the library. After I remember to breathe, the first word that comes to mind is divine. Rising from a floor of giant white marble diamond tiles outlined in black marble are ornate dark wood galleries of bookcases accented with gold. These then stretch upward into a blind arcade gallery of sorts of gold and dark pine green Gothic arches. If you hadn’t gotten the Gothic message, a gargantuan wrought-iron chandelier dangles in the middle of it all. And yet despite being a neo-Gothic library of dark wood and dark green, the space is far from somber and stuffy. That chandelier, in fact, isn’t often turned on as the whole reading room is flooded with natural light pouring down from a glass dome crowning the space. Indeed, the whole space with its ornamentation and pointed, tine-like arches has the feel of a crown turned into a library.

But in a country best known for 20th century architecture from the likes of Oscar Niemeyer, one could be forgiven for asking, what in the hell is such a lavish Old World library doing in the heart of this tropical party city?

One could start by laying the various events that led to the Portuguese royal family of Braganza ruling the Empire of Brazil from Rio de Janeiro at the feet of Napoleon, who in just a decade upended so much of the European order. But the weakened state of Portugal (relegated to a bitterly clingy ally of the U.K.) goes back to 1755 and a massive earthquake that destroyed much of Lisbon and wiped out a large part of the resurgent kingdom’s fortune. In the ensuing decades, Portugal’s struggle to defend its far-reaching empire became ever more strained, and even its own home territory became at risk due to Napoleon and one colossally bad marriage. (The king at the center of this tale, João VI, married Princess Carlota Joaquina of Spain who spent much of their marriage plotting against her own husband on behalf of her native Spain. It is believed he may have died from arsenic poisoning.)

In the fall of 1807, with Napoleon’s forces about to take Lisbon, the Portuguese royal family and as many of their retinue who could make the scramble piled into ships waiting in the pouring rain. The clock on the king’s game of feigned appeasement to Napoleon had run out, and so, incredibly, the entire court of one of Europe’s most storied kingdoms decamped to the New World, where the Portuguese Empire would be ruled from Rio de Janeiro. It meant a dramatic transformation for colonial Rio—architecturally, culturally, and politically.

While the Braganza established themselves in Rio, back in Europe in 1815, Napoleon was defeated for good. But the post-Napoleon situation in Portugal was a mess. First, João had actually only been ruling in his mother’s name—she’d been declared mentally unfit—until she died in 1816. The king himself did not return to Portugal until 1821 due to conflicts there over what type of monarchy should be re-established after Napoleon. Not long after his return, the Portuguese empire had another shock—the son João had left behind to govern Brazil had sided with Brazilian independence and declared it its own country.

While the Braganza dynasty would rule Brazil until 1889, a period that with the usual caveats (slavery being a big one until the daughter of the emperor abolished it) was a relative golden age of stability and military victories for Brazil compared to its neighbors. But events back in Portugal were chaotic, and that country’s messy politics is in fact the reason we have this jewel of a library in Brazil today.

João VI’s return to Portugal did little to bring stability. For the remainder of his rule and in the ensuing decades, Portugal, like Spain, was ripped apart by conflict between progressive reformers and those who believed in an absolute monarchy. Upon his death, the former supported his son Pedro, who had declared Brazil’s independence but then came back to rule Portugal.

The absolutists, however, supported his other son, Miguel, who ruled Portugal in the early 1830s and jailed, tortured, and executed many of those seeking political freedoms. As a result, a number of political refugees fled to Rio de Janeiro, now ruled by Pedro’s son Pedro II.

On May 14, 1837, a group of 42 Portuguese immigrants gathered at the house of one of those refugees in Rio de Janeiro. They were a mix of businessmen, lawyers, and intellectuals—but all were products of a generation where the pursuit of knowledge was essential and all were passionate about their mother tongue. Like many of their contemporaries in France, Britain, and the U.S., they were confronted with the issue of a thirst for knowledge by an expanding middle class frustrated by the high cost of books. A solution already existed in those places. In France, it was called a cabinet de lecture, and in Britain and the U.S., subscription and circulating libraries. In essence, for a fee, you could borrow books or periodicals (as subscriptions to these were also expensive). The two most famous in America were Benjamin Franklin’s Library Company of Philadelphia (1731), and, you guessed it, Redwood Library in Newport (1747).

So, these ardent book lovers created their own subscription library, a Gabinete Português de Leitura (the Real, or Royal, was added later). Unlike a lot of other subscription libraries, however, there was no plan for the library to turn a profit. José Marcelino da Rocha Cabral, the first president of the association and a man who had spent time in the prisons of King Miguel, declared that the group’s mission would reflect the idea that “in no other respect have [we] obtained such advantageous results for the happiness of men and the glory of nations as in their application to the progress of literature and science, for the betterment of mankind.” Besides general enlightenment, it would, the group promised, according to Antonio Alves-Caetano’s O Real Gabinete Português de Leitura do Rio de Janeiro, “help restore the literary glory of their fatherland.”

Over the decades, the members would amass such a collection of books (novels, histories, scientific, religious, and business texts eventually composing the largest collection of Portuguese works outside of Portugal) that new headquarters were always needed. In the 1860s, the members finally got serious about the need for a permanent space that matched the loftiness of their ambitions. But it would be another two decades before anything really happened.

I felt sick. Gluttonous as always, I’d stuffed myself to the edge of nausea with the perfect yellow custard treats covered in powdered sugar found in Belem, this now famous former suburb of Lisbon. Few destinations around the world have exploded in popularity like Lisbon. Nursing a stomach ache, I was headed to this uber-popular city’s most famous sight and one of the few glimpses of the glory that existed prior to the earthquake—Jerónimos Monastery.

What pictures don’t quite capture about this space is its scale—from outside it towers above and extends into the distance for what seems an eternity. Inside, the church’s spindly columns shoot up into spider-webs of vaulting that mesmerize.

Jerónimos Monastery

The cloisters that wind their way around green courtyards are of such beauty one almost could consider taking up the robe. It is the greatest example of Manueline architecture—the ornate and imaginatively decorative late Portuguese Gothic style that so able blended a panoply of influences.

And in the late 19th century it was in ruins due to neglect.

The architect tasked with its restoration, Rafael da Silva Castro, was asked by the Rio’s library members to design their new building in the early 1870s. While that may seem an obvious choice, given the prominence of Jerónimos, it was also another example of how much these members were focused on the motherland.

After the dominance of neoclassical architecture in the 18th and early 19th century, a longing for an “authentic” national architecture turned what was once a century-old fascination with medieval gothic style into a full blown architectural and decorative movement. In France, the most significant moment in this period was likely when Napoleon III tasked Viollet-le-Duc (designer of Notre Dame’s restored but now incinerated spire) with rescuing the monumental Château de Pierrefonds. In Germany, the Cologne Cathedral was finally completed and Ludwig II created Neuschwanstein, his medieval Sleeping Beauty castle. Britain was even earlier with icons like Strawberry Hill House.

In Portugal, the style was called neo-Manueline, and birthed such beauties as the Quinta da Regaleira, Buçaco Palace Hotel, and Rossio train station. Of course the members of a library dedicated in part to promoting the legacy of Portugal would be fans of such a style, and commission a building that today is held up as one of its best examples. For inspiration, Cabral wrote, it should “follow the architecture of the Jerónimos Monastery.” Even the limestone cladding the building would be shipped from Portugal.

In 1880, the tercentenary of the death of Luís Vaz de Camões, Portugal’s greatest poet, construction began on the library with Emperor Pedro II looking on. For those who want to try to figure out the utterly perplexing old Brazilian way of writing out numbers, it cost 6:000$000 reais (or six contos de reais). The architect in Brazil who made Cabral’s designs happen was Frederico Jose Branco.

On September 10, 1887, the building was finished. A year and two months later, on December 22, 1888, all 120,000 volumes in the collection had been installed and the library was officially complete. On both dates the building was inaugurated by the writer Joaquim Nabuco, one of Brazil’s most famous writers and one of its loudest voices advocating for abolition of slavery.

On the building’s street-facing facade are four niches, each containing a statue of one of Portugal’s most illustrious figures. Three were explorers and conquerors: Pedro Álvares Cabral, Infante D. Henrique (Prince Henry the Navigator), and Vasco da Gama. The fourth was Luís de Camões himself. Over the decades, the collection grew to the point it is at today, with over 400,000 volumes. In addition to priceless books (like a first edition of Camões’ Os Lusiadas), the library is also a repository for gorgeous items like an ornately carved dark wood ciborium (miniature canopy on pillars used to house a precious object) and elaborate works of silver.

Best of all? This library that makes so many of the must-see lists around the web (and even Massimo Listri’s book on beautiful libraries) is open to the public, and anybody can go in, register, settle into one of the marvelous embossed black leather chairs, and read the books in their collection.

Hopefully, you’ll be more successful than I was all those years ago in Redwood.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.