World-renowned archeologist, MSU professor who discovered lost city of Ubar has died

A renowned Middle East archeologist and professor emeritus at Missouri State University — whose 1992 discovery of the ancient city of Ubar drew international acclaim — died unexpectedly Saturday in New Mexico.

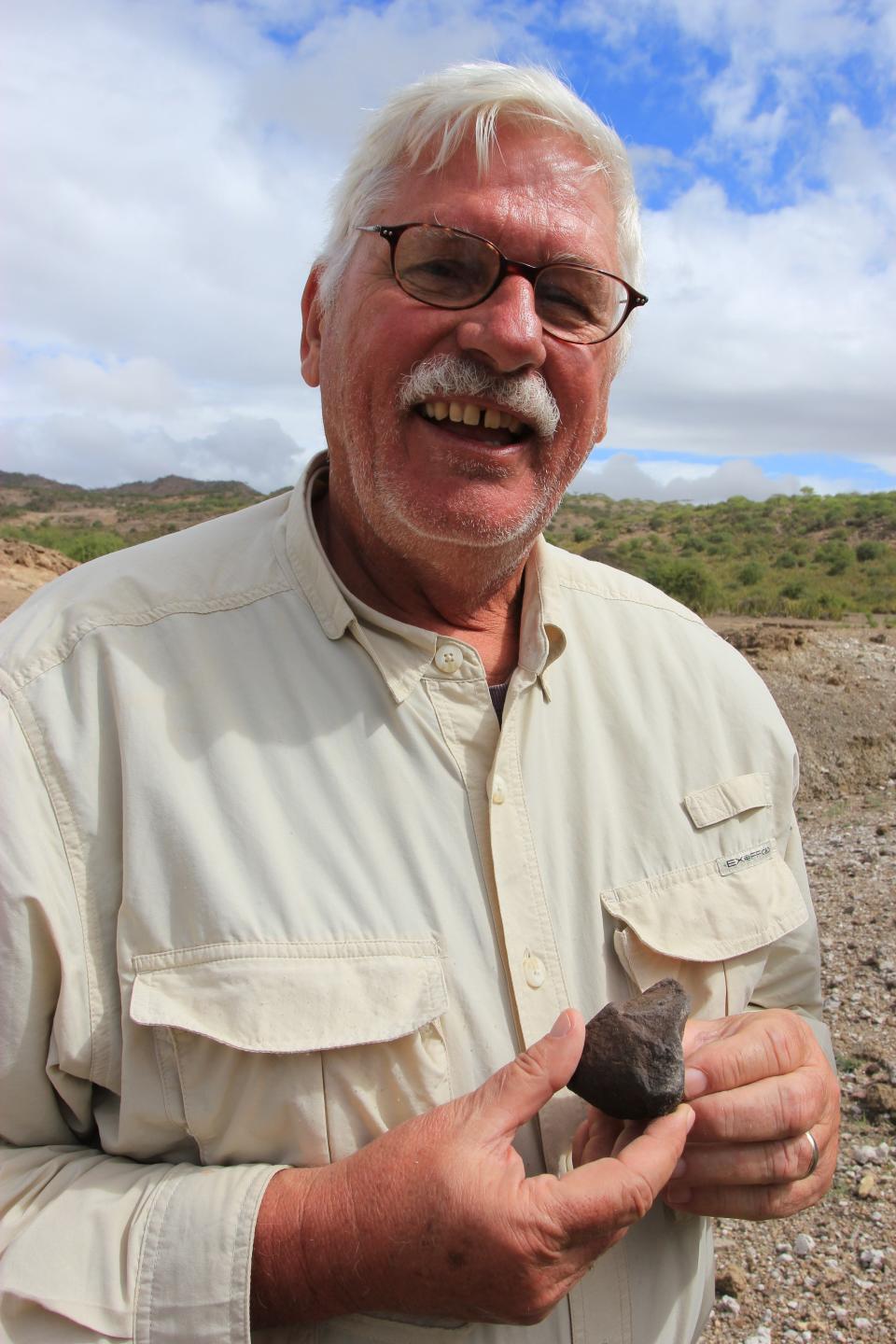

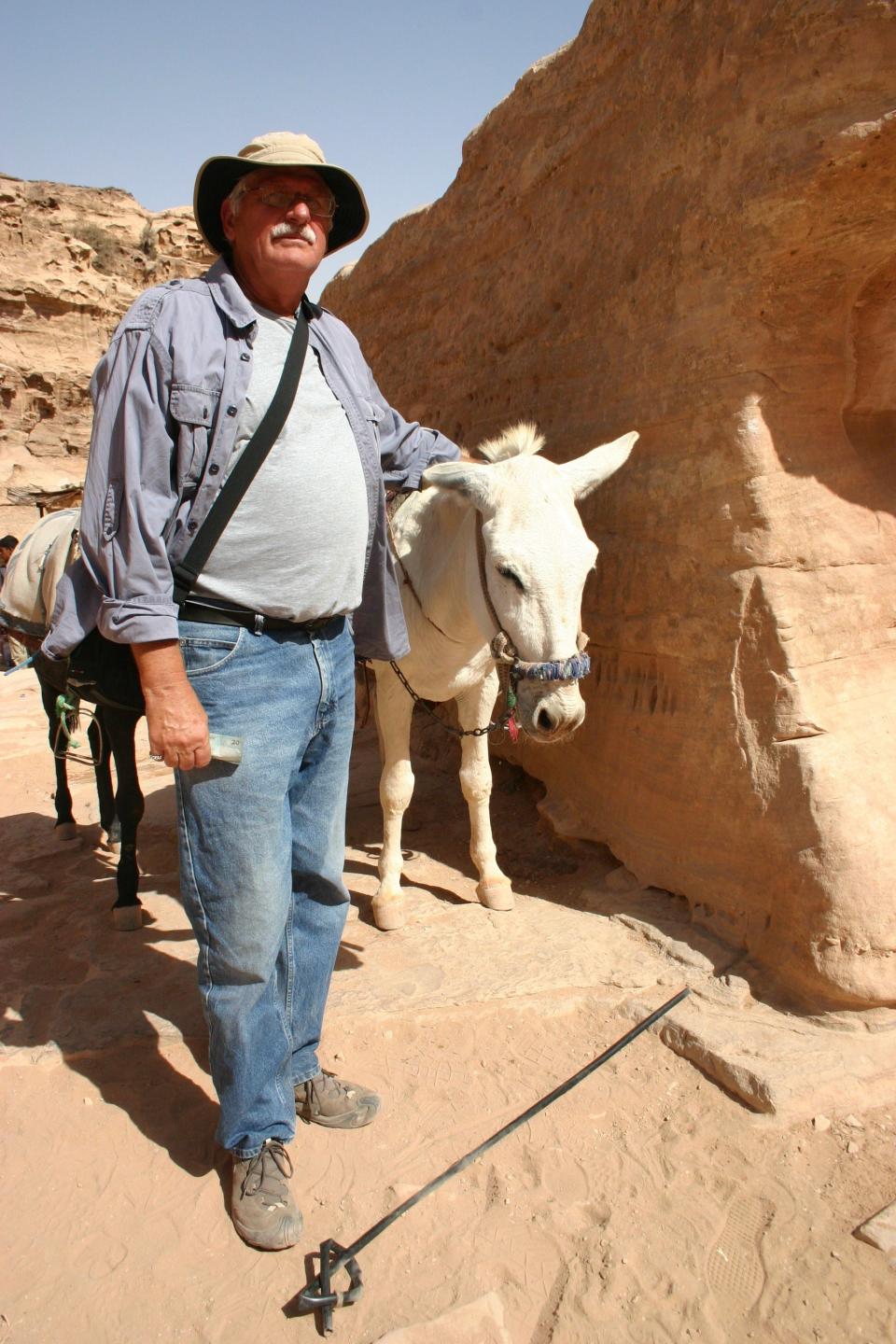

Juris Zarins, 78, spent nearly three decades educating future archeologists and anthropologists at Missouri State. He took advanced students on expeditions to Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Oman and Yemen.

His discovery of the ancient city on the southern coast of the Arabian Peninsula was hailed by Time magazine as the No. 3 scientific development of 1992. Discover magazine called it one of the top science stories of that year.

"He was an engaging person, someone who had lots of energy, a wonderful sense of humor and a command of his field, the literature and the history of the time periods he was working with," said Victor Matthews, who retired June 30 as dean of the College of Humanities and Public Affairs. "He was really a wonderful source of information and a great colleague."

Missouri State, where Zarins taught from 1978 to 2006, listed the archaeological find among its top milestones in the first century of the university.

In the mid-1990s, Zarins and his work was featured on a Nova PBS program called "Lost City of Arabia."

Matthews added: "He was the Indiana Jones in essence of the department."

Matthews, who spent 39 years at the university, said Zarins structured his contract so he was able to be in the field, often overseas, for a portion of most years. He took students on expeditions and brought that hands-on knowledge back to the classroom.

"Juris was kind of a unique character. He loved his work as an archeologist, he enjoyed his students but always felt his place was more in the Middle East than it was here," he said.

He said the work of Zarins and other anthropologists grew interest in the Missouri State program.

"Fieldwork was really a big deal and it set the stage ultimately for what the program has become since then with a real emphasis on doing study away," he said.

Zarins, drafted by the U.S. Army, served in Vietnam

Born to Latvian parents in Germany at the end of World War II, Zarins completed his undergraduate work at the University of Nebraska and a doctorate in Ancient Near Eastern Languages and Archeology at the University of Chicago.

In between degrees, he was drafted and served in the First Calvary Division of the U.S. Army in Vietnam in 1969 and 1970.

His graduate work included excavations in Sweden, France, Turkey and Iraq. He studied cuneiform writing and his dissertation was on the domestication of equids, a mammal in the horse family in Mesopotamia.

Zarins became an authority on pastoral nomadism in the Middle East and wrote about obsidian trade in the Red Sea, early use of indigo, and the domestication of the camel.

Early on at Missouri State, Zarins was also an archeology and museum advisor with the department of antiquities in Saudi Arabia.

He spent three years as a consultant archeologist in Oman in the 1990s.

Shortly after retiring from Missouri State, Zarins was the archeology field director at the American Foundation for the Study of Man in Yemen.

He spent six years as archeology and museum consultant in Oman for the Office of His Majesty the Sultan's Advisor for Cultural Affairs.

Finding lost city using images from space

In the early 1990s, officials with Missouri State — then known as Southwest Missouri State University — said the role Zarins played in finding the lost city of Ubar increased interest in the anthropology program.

Zarins was chief archeologist for the expedition but his assistant and a group of MSU students were also part of the team.

Here are details about the discovery, according to 1992 and 1993 articles in the News-Leader:

Scientists believe that Ubar sank beneath the Arabian sand 2,000 years ago;

The city once flourished as the lucrative trade center for frankincense, a fragrant gum resin harvested farther south;

According to legend, Ubar known as Iram, the "city of towers" was destroyed in a violent windstorm sent by an angry god;

Before his untimely death in 1935, Lawrence of Arabia planned to search for the city, which was a probable source for the frankincense that the three wise men presented to the baby Jesus;

Findings include parts of the city's eight 30-foot mud-brick towers, various rooms, incense burners and thousands of pieces of pottery. They also found five pieces of a chess set that dates to the 10th century A.D.

The expedition used pictures from the space shuttle Challenger to find Ubar in a remote area of Oman.

More: Historic marker celebrating area's first African American USO Club installed in Lebanon

In a 1992 article, Zarins explained that the modern technology used to find and excavate the site was part of why it was noteworthy.

"There is the Biblical aspect and the fact that Ubar was known for the trade of frankincense," he said in 1993. "It gives a positive image to the country of Oman."

The discovery suggested the frankincense trade routes crossed the Arabian desert thousands of years prior to when historians and archeologists had originally estimated.

Matthews said the attention Zarins received for his work helped raise the profile of the university and the program.

"Anytime you get good publicity in major outlets like National Geographic and PBS and so on, it is always great for the university and I'm sure it attracted students," he said.

"If we were talking about someone who made an impact on people's lives and who was a memorable character, that is Juris."

Lynne Newton, his wife for the past 16 years, served as co-director of a groundbreaking archaeological survey called the Mahra Archaeology Project, along with George Hedges, from 1996 to 2001.

Newton and Zarins were field partners for excavations at Al Baleed, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and they worked to continue an archaeological survey of Dhofar.

At the time of his death, he was researching a book he planned to write.

"Juris was the love of my life. He trained me as an archaeologist and I am so grateful for the opportunity to join our lives and work in Oman and Yemen," Newton said Monday. "He was brilliant, funny and loving — he lit up any room he walked into. He touched so many peoples' lives and it is a void that cannot be filled."

Zarins, who lived in New Mexico with Newton, had four sons, one daughter and four grandchildren.

The family is planning a memorial in Springfield.

Claudette Riley covers education for the News-Leader. Email tips and story ideas to criley@news-leader.com.

This article originally appeared on Springfield News-Leader: Renowned MSU archeologist who discovered lost city of Ubar remembered