In World War II, how Pearl Harbor bombing led Delaware coast to prep for enemy attack

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

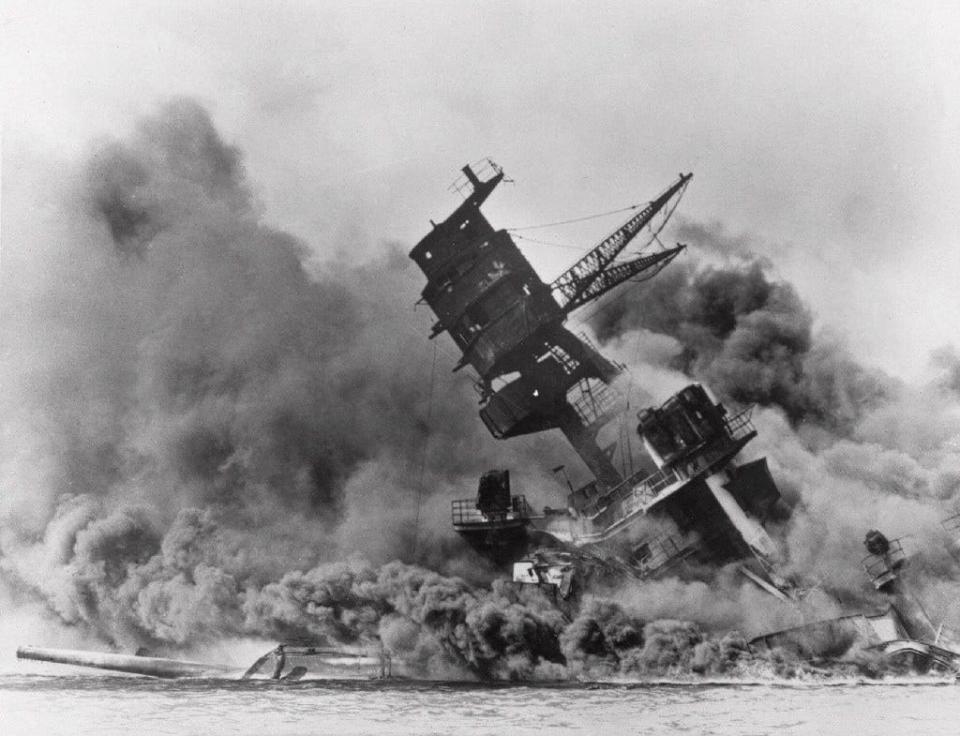

At noon on the second Monday in December 1941, coastal residents gathered around their radios to hear President Franklin Roosevelt announce, “Yesterday, December 7th, 1941, a date which will live in infamy, the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.”

With a calm and steady voice, the president then launched into a litany of other attacks in the Pacific. In less than seven minutes the president’s speech was over, and he concluded “I ask that the Congress declare that since the unprovoked and dastardly attack by Japan on Sunday, December 7th, 1941, a state of war has existed between the United States and the Japanese Empire.”

The United States was at war, and Lewes and other coastal communities were on the front lines.

How coastal communities were impacted after Pearl Harbor attack

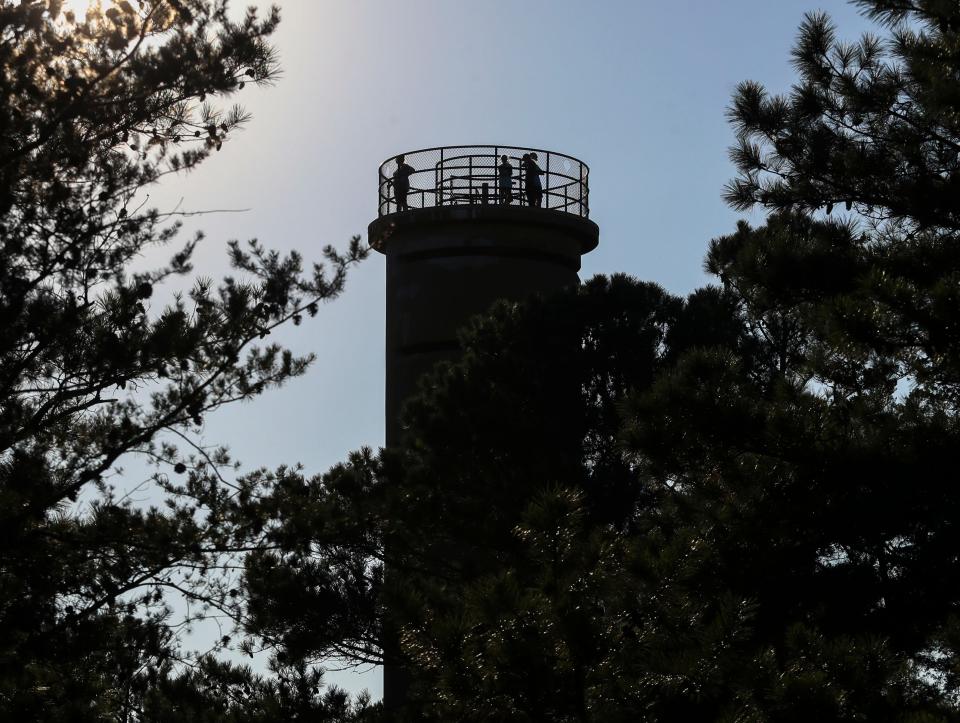

In the days after the Pearl Harbor attack, local authorities organized civil defense efforts to combat an enemy air raid.

The Lewes newspaper, the Delaware Pilot, remarked on Dec. 12, “In 1939, when the present World War began, the British people had eleven months before their first air raid in which to prepare defensive measures. In 1941, when the war reached the possessions of the United States, it started with an air raid. The comparison indicates clearly the tremendous job ahead of the civilian population of our country if the damage and destruction of the surprise raid on Hawaii is not to be repeated when the first enemy planes fly overhead.”

The newspaper also reported that hostile planes had been sighted over San Francisco on Monday night. Although this report was a false alarm, there was speculation that long range bombers, seaplanes refueled by submarines, planes from aircraft carriers or seaplanes operating from mother ships might attack Lewes.

“In any case," the Delaware Pilot, reported, “they could do enough damage to Fort Miles, Fort Saulsbury, the Nylon Factory or other vital points to make the trip across the ocean worthwhile.”

Plans for a possible enemy attack took shape quickly

In Lewes, community leaders, led by Mayor Thomas H. Carpenter, prepared a response for a possible enemy attack. Plans were devised to coordinate efforts of the police and fire departments, Beebe Hospital, the Red Cross, and other community organizations in the event of bombs falling on Lewes.

Carpools were organized to ferry children to a safe location outside of town, where first aid stations were to be set up to avoid overwhelming Beebe Hospital.

Five days after the Pearl Harbor attack, the Delaware Coast News, carried a list of “Suggestions to Heed During Air Raids” that included preparing a “refuge room for you and your family,” recommending filling bath tubs ¾ full of water, and having at least 5 gallons of sand on each floor to fight fires.

Over a month later, on the eve of the area’s first air raid drill, Delaware Coast News printed detailed air raid instructions dealing with motorists who were on the road when a raid began, extinguishing all lights that shine outside, and not using the telephone.

In addition, civilians were reminded, “In the house, go into your refuge room and close the door … Appoint one member of the family for your home warden to remember all rules. Mother makes the best!”

Although there were submarine attacks on the Delaware coast, and scores of survivors were landed at Lewes, the town never came under direct attack. Air raid drills and blackout regulations continued throughout the war.

The five gallons of sand stored on each floor of Lewes homes was never needed, but mothers continued to be the best person to remember and enforce the rules.

Principal sources

Speech by Franklin D. Roosevelt, New York (Transcript), Library of Congress, Speech by Franklin D. Roosevelt, New York (Transcript) | Library of Congress (loc.gov)

Delaware Pilot, Dec. 12, 1941.

Delaware Coast News, Dec. 12, 1941; Jan. 30, 1942.

This article originally appeared on Salisbury Daily Times: After Pearl Harbor attack, why coastal Delaware was on high alert