How the world's first heart transplant almost didn't happen due to medical 'rivalries and immense hostility'

On Aug 18 1979 at Papworth hospital near Cambridge, Terence English took a call from a friendly registrar at nearby Addenbrooke's and learnt two equally crucial facts.

The first was that a healthy donor heart had become available.

The second was that the registrar’s boss, Professor Roy Calne, was out of town.

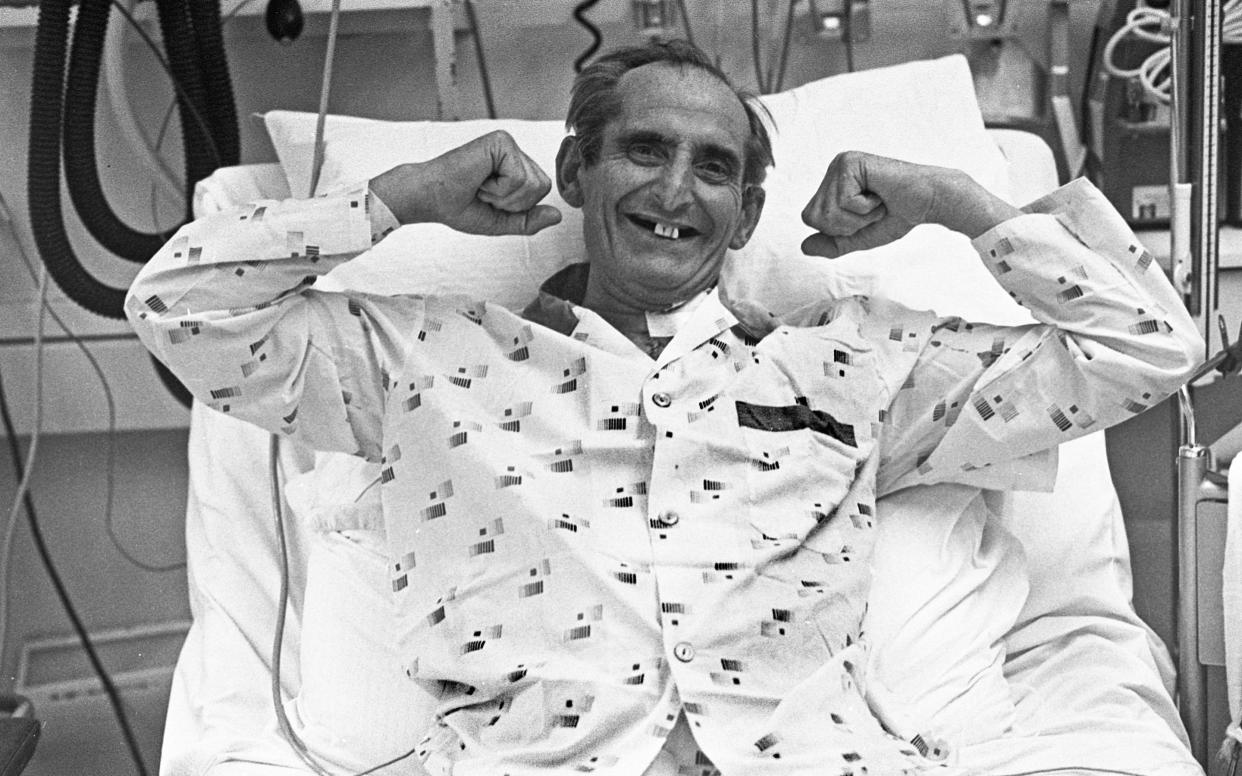

A few hours later, English sewed the organ into the chest of a gravely ill 52-year-old builder from London called Keith Castle.

Despite being a poor candidate due to his heavy smoking, Castle survived, regaining full consciousness and going on to live for another five years.

Britain’s heart transplant programme was born.

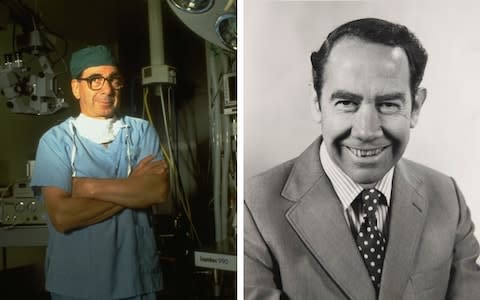

Forty years on, Sir Terence, as he now is, reveals the rivalries and immense hostility from the medical establishment that nearly strangled the programme at birth.

“God, it was so crucially important that we succeeded,” he told The Sunday Telegraph.

“There were a lot of cardiologists who didn’t want to see it happen, and the Department of Health was furious.

“But Keith was a great survivor.

“I actually think he did more in the months that followed to publicise the value of heart transplantation than I ever could.”

The first attempt at a heart transplantation in Britain had actually taken place 11 years earlier, but the patient had lived for only 45 days.

Similarly poor outcomes in a number of patients over the following year persuaded health chiefs to ban the practice.

But by 1979 the powerful immunosuppressant drug ciclosporin had been discovered, which helped prevent the immune system rejecting donor organs.

During that time Sir Terence had been training with top US transplant surgeons, meanwhile building up a team of specialists at Papworth, waiting for the mood to change.

He was refused funding by the Department of Health, and told he must under no circumstances perform a heart transplant, but the NHS manager for Cambridgeshire believed in the programme and gave the money for two procedures.

However, this did not impress (now) Sir Roy Calne, a kidney transplant pioneer to whom Sir Terence had previously promised they would initiate a heart transplant programme together at Calne’s Addenbrooke’s hospital base.

Sir Terence says the resulting disagreement was so profound that Sir Roy instructed units under his control - where most of the donors arrived - not to send donor hearts to Papworth.

“A lot of the units that were sending [donor] kidneys were told he wasn’t going to accept any if they were also sending hearts.

“It was difficult - I could have handled things better, I think.”

Sir Roy had not accounted for his senior registrar, Paul McMaster, who believed Sir Terence should have the chance to operate and offered the heart in his superior’s absence.

Subsequently the president of Medecins Sans Frontieres UK, McMaster had done exactly the same thing seven months earlier.

However, the recipient on that occasion, Charles McHugh, had suffered brain damage while waiting for the organ and died three days after the operation.

“I had to go to the Department of Health and explain what had happened,” said Sir Terence.

“But they did not know that I had one more shot, and that I was going to use it.”

Even after the success of Keith Castle’s transplant, officials in Whitehall were initially reluctant to fund further transplants.

Sir Terence’s unit had to get by with grants from the British Heart Foundation and the reclusive millionaire Sir David Robinson, founder of Robinson College at Cambridge University.

During these early years the survival periods gradually improved thanks to better understanding of how to use ciclosporin.

Currently around 200 heart or heart-lung transplants are carried out on adults every year in the UK, around half of which take place at Papworth.

Tomorrow the hospital hosts an event which will be attended by relatives of Keith Castle, and former patients of Sir Terence, including one woman who has lived 37 years since her transplant.

“It’s been a long journey, but it’s been worth it, and eventually a lot of good came out of it,” said Sir Terence.

“You just had to exert a bit of tenacity of purpose.”

Sir Roy Calne, who could not be approached for comment, went on to perform the world’s first liver, heart and lung transplant in 1987, and the UK’s first intestinal transplant in 1992.

Following Sir Terence’s unsuccessful first attempt at a heart transplant in January 1979, Sir Roy wrote to him expressing concern “at the effect that requesting for heart donation may have on our kidney donation”.

Professor John Wallwork, who worked with both men and is currently chair of the Royal Papworth Hospital, said: “There was a certain amount of friction”

Reflecting on scepticism in the wider medical profession, he added: “Terence did exactly what you should do.

“He did his homework, took advice from other people, then did it methodically, which is why he succeeded.”

Professor Jeremy Pearson, Associate Professor at the British Heart Foundation said: “One of the British Heart Foundation’s first grants was given to scientists conducting early research into transplant techniques.

“From that day in 1963 to the present day, the BHF have been funding pioneers just like Sir Terence to carry out cutting-edge research to improve surgical techniques, prevent transplant rejection and develop medical devices to help the failing heart.”