Wrightsville Beach history: When Shell Island was an island, and a Black beach resort

![The beach is relatively empty even during the summer on the north end of Wrightsville Beach in 2021. The north end is the largest part of Wrightsville Beach that is undeveloped. [MATT BORN/STARNEWS]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/oeR7Ti0ahXT8tDP5ISjZLw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTEyNDI7aD04MTg-/https://media.zenfs.com/en/star-news/bae3031f97e5322edf199623bc6df0af)

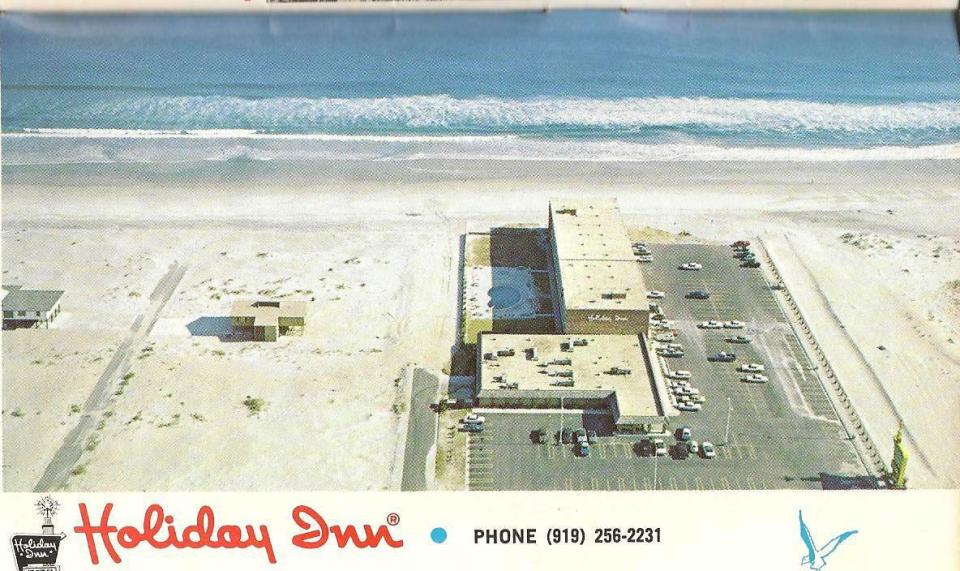

In June, the Holiday Inn Sunspree resort at Wrightsville Beach unveiled a revamped look and a lengthy new name: Lumina on Wrightsville Beach, a Holiday Inn Resort.

Lumina, of course, is an homage to the fabled Wrightsville Beach pavilion of old, which was demolished in 1973.

But what many visitors to the area, as well as many new residents, might not know is that, just 60 years ago, the land the hotel sits on wasn't land at all. Rather, it was an inlet, Moore's Inlet to be exact, and it separated Wrightsville Beach from what's known as Shell Island, which back then was an actual island.

"At times you could, when the tide was low," literally walk over to Shell Island from Wrightsville Beach, said Elaine Blackmon Henson, a Wilmington historian.

More: 3 things to know about a renovated hotel-and-restaurant resort in Wrightsville Beach

More: Heart of the Town: The undeveloped north end of Wrightsville Beach has changed little over the years

For the latest episode of Cape Fear Unearthed, the StarNews' local history podcast, we talk to Ray McAllister, author of "Wrightsville Beach, The Luminous Island," about this particular part of Wrightsville Beach history, and about Shell Island itself, which has its own culturally significant history.

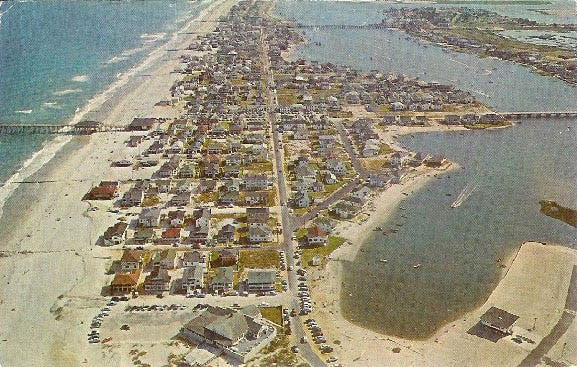

To ride up and down a built-out Wrightsville Beach today, it's hard to imagine that, less than a lifetime ago, the "north end" of Wrightsville Beach was marked by The Surf Club on Mallard Street.

"I can't tell you how different it was back then," said Robert Rehder, a 1966 graduate of New Hanover High School whose family had a cottage on Shearwater Street when he was growing up in the 1950s and early '60s.

"It wasn't much," Rehder said. "Not like the big beach houses they have now."

Still, they'd typically stay from May to October, Rehder said, swimming, fishing, water skiing and even making jaunts across Moore's Inlet to Shell Island.

Once, Rehder said, he and a friend decided to swim to Shell Island at high tide, knowing they could walk back to Wrightsville later when the tide was lower. As they were swimming over, however, someone saw them, assumed they were drowning and alerted a lifeguard, who tried to initiate a rescue, Rehder recalled with a laugh.

Once you got onto Shell Island, "It was no man's land," he said, with no structures other than "maybe a fishing shack."

"It was really wild back then. The fishing was outstanding," Rehder said. On the sound side of Shell Island "the backwater was pristine and cool and clear," with glassy water perfect for water skiing.

Rehder was a teenager when Moore's Inlet was filled in during the mid-1960s, and "that gave them the leeway to start developing" Shell Island, he said.

The first homes started to appear on Shell Island in the late 1960s, and by 1968, the first iteration of the Holiday Inn would be constructed at its current location.

Nowadays, Shell Island is densely packed with beach homes and hosts the substantial Shell Island Resort, built in 1986.

A century ago, however, Shell Island was imagined as something very different than it is today.

In "Wrightsville Beach, The Luminous Island," McAllister includes a chapter on a beach resort for Blacks that existed on Shell Island for three years in the 1920s before coming to an end, its existence nearly lost to the sands of history

Writing for The Assembly, an online North Carolina magazine, earlier this year, Wilmington resident Marc Farinella chronicled that attempt to establish a resort for Black beachgoers on Shell Island.

Farinella, who has a long career as a political communications specialist, including a stint as chief of staff for Missouri Gov. Mel Carnahan in the mid-'90s, moved to the Wilmington area in 2018.

As he began to delve into the area's history, he said he started seeing references to a Black beach resort on Shell Island about which little had been written. So he decided to research it for himself, digging through old newspaper clippings and looking for long-forgotten documents at the register of deeds.

"It's a really interesting story," Farinella said. "It was a really bold project that, had it succeeded, would've changed the face of the area."

The story goes back more than 100 years, in the midst of segregation and the Jim Crow South. Blacks at the time weren't allowed alongside whites at most, if any, area beaches.

In 1917, area Blacks petitioned to be allowed to visit the South end of Wrightsville Beach, but those efforts were not successful.

A few years later, Farinella said, Thomas Wright — for whose family Wrightsville Beach was named — along with other partners, including the Parmele family, began to establish what they envisioned as a Black beach resort on Shell Island, which at that time was completely uninhabited.

By 1923, Tidewater Power — which ran the electric trolley line between Wilmington and Wrightsville Beach and was owned by Hugh MacRae, one of the plotters behind the 1898 coup and massacre, during which dozens of Wilmington Blacks were killed — was running a line to a ferry terminal operated by the Stone Towing company that would take Black riders to Shell Island.

Wright's plan was to sell about 275 cottages on Shell Island, Farinella said, but only two sold. A pavilion, a boardwalk and other structures were built on Shell Island as well, but mysterious fires in June of 1926 destroyed many structures on the island.

Some sources cite a "series" of fires, "But I only found information about one fire," Farinella said.

The Shell Island venture never went anywhere after that, and the Atlantic Ocean eventually claimed whatever structures were left behind, McAllister said.

Farinella said he sees the Shell Island Beach project — advertised nationally as a "Negro playground" — as "a failed business venture," but acknowledges there were racial pressures as well.

McAllister said some newspaper accounts of the day strove to make abundantly clear to potential tourists that the races were kept strictly separate on Wrightsville Beach and Shell Island.

At any rate, Shell Island is a "really important cultural site," Farinella said. "There were very few Black beach resorts anywhere, let alone in the Jim Crow South."

For that matter, the Wilmington area had two, as the Seabreeze resort for Blacks near Carolina Beach was taking shape in the 1920s as well. One big difference, Farinella noted, is that Seabreeze, which would become a destination for decades to come, was mostly owned and financed by Blacks, while Shell Island was owned and developed by whites.

More: Historically Black Seabreeze neighborhood could see denser development with rezoning

Gradually, over the next 40 years, Shell Island returned to its natural state.

Still, filling Moore's Inlet to connect Wrightsville Beach and Shell Island had been a point of discussion since at least the 1930s, Farinella said. Wrightsville was suffering from erosion, and "the thought was that by connecting the two islands, they might be able to mitigate the erosion."

In 1960, Farinella said, the Parmele and Wright families announced a proposal to connect the two islands, and by the middle 1960s the Army Corps of Engineers was at work filling the inlet.

Farinella said it's unclear whether the families' proposal and the Corps' plan were connected, but he said the families did pay some of the costs of having the inlet filled.

That paved the way for the full development of the newly enlarged Wrightsville Beach, which went from being two-and-a-half miles in length to four.

The ocean wasn't quite through with Shell Island, however. Past versions of the Holiday Inn have dealt with damage from the ocean, McAllister said. By the mid-1990s Mason's Inlet was mere yards away from Shell Island Resort and was threatening other homes.

To walk that northernmost stretch of Shell Island now is to perhaps catch a glimpse of what the island was like many decades ago.

Contact John Staton at 910-343-2343 or John.Staton@StarNewsOnline.com.

This article originally appeared on Wilmington StarNews: Wrightsville Beach history: When Shell Island was a Black beach resort