Writers' strike: Hollywood scribes picket studios for better pay. 'It's not sustainable'

Just hours after a midnight deadline to reach an agreement with major Hollywood studios on a new contract expired, thousands of striking members of the Writers Guild of America set down their pens, stepped away from their laptops and took their fight to the streets on Tuesday.

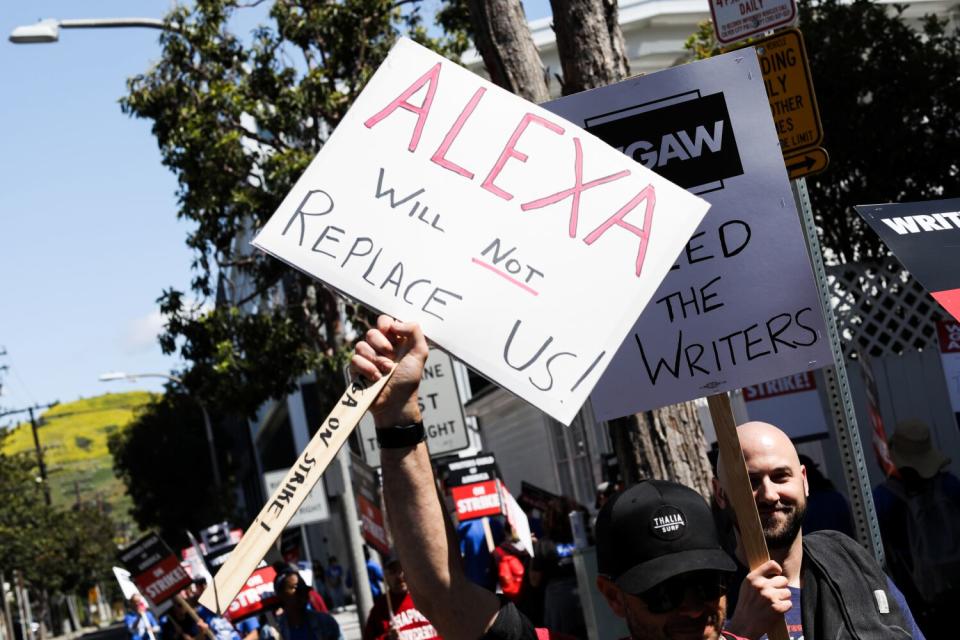

Forming picket lines outside more than a dozen studios and production facilities in Los Angeles and New York, including the headquarters of Netflix and Amazon Studios, writers hoisted placards and chanted in unison to demand what they regard as fair compensation and working conditions in an industry that has been upended by the rise of streaming.

Months of mounting tension over negotiations between the WGA and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, which represents the studios in labor relations, exploded into public view, with Hollywood writers walking off the job for the first time in 15 years.

Outside the Sony Pictures lot in Culver City, Ashly Burch, who has been working on the Apple TV+ series "Mere Mortals," spoke of the unprecedented challenges today's writers face, even amid the studios' and streamers' seemingly insatiable demand for content.

“If you’re beginning staff, like a story editor, it’s not sustainable to live off of this profession anymore," Burch told The Times, as passing cars honked in support. Fellow strikers wielded signs bearing slogans, including "Never Give Up! Never Surrender!" and "Because TV Needs More Than the Kardashians."

"I was at a WGA meeting before this, and so many people there had second jobs because they couldn’t afford living off their writing," Burch said. "No one should struggle to pay rent or their mortgage while they’re writing on a show."

The protests represent a show of force for the guild's 11,500 members, 98% of whom voted last month in favor of a strike authorization, as they push the AMPTP to address the steady erosion of their pay caused by Hollywood's shift toward streaming, which has radically transformed the way entertainment is financed, produced and consumed.

Despite the streaming boom, writers are finding themselves working longer hours for less money, with residuals for reruns and home video sales drying up. According to a recent WGA survey, the median weekly pay for writer-producers has declined by 23% over the last decade when adjusted for inflation.

Several hundred WGA members marched in front of the entrance to the Fox lot in Century City, some with infants in tow, others carrying signs with such slogans as "We Just Want 2% From the 1%" and "Let’s Reboot a Living Wage.”

Television writer Betsy Thomas, a member of the WGA’s negotiating committee, said the mood in the final hours of talks with the AMPTP was grim.

“It was a very big, heavy decision that we had to make," Thomas said. "We really wished that we had a path forward. And we're hoping that we do. … But when they made their last offer, we realized, we're not going to get there. Their responses on fundamental existential issues that are affecting writers were just all insufficient.”

In a statement Monday night, the studio alliance said it offered “generous increases in compensation for writers as well as improvements in streaming residuals.”

The group said it was prepared to improve the offer but was “unwilling to do so because of the magnitude of other proposals still on the table that the Guild continues to insist upon.” The sticking points, according to the AMPTP: the guild’s demands over mandatory staffing levels and duration of employment.

Outside Netflix’s Los Angeles headquarters, WGA lead negotiator Ellen Stutzman said that, after weeks of grueling talks, she felt energized to see so many members picketing. Much of the guild's attention was focused on the Netflix picket line. The streamer played an outsize role in upending the entertainment industry.

“I’m so happy to be out here with writers because it’s been so incredibly frustrating to be in a windowless conference room dealing with company representatives that do not want to address writer concerns,” Stutzman said. “We will be ready to reach a deal when the companies want to have a real conversation.”

Silver Lake-based Luvh Rakhe, who was a producer on “New Girl” and a member of the WGA’s negotiating committee, said that it was important for him to put pressure on Netflix, specifically.

“Across all levels of writers in L.A., we have felt the ripple effect of the uncertainty that the new business models have put into our lives," he said. "We feel the precariousness.”

Outside the Disney lot in Burbank, where picketers marched in front of three separate gates, Krista Vernoff, showrunner for “Grey’s Anatomy” and “Station 19," said she was there to advocate on behalf of entry-level writers, for whom today's entertainment industry offers little support.

“When I entered the industry, it was not only viable and possible to make a living as a writer, it was the thing we reached for,” said Vernoff. “And once we broke through, we could make a living. This is no longer true... What used to be a studio culture has become a streamer culture, but they don't want to let us into the streamer profits. And it feels like they're trying to turn everyone who works in Hollywood into Amazon workers. "

Many people striking Tuesday recalled walking similar picket lines at the last writers' strike in 2007, which lasted 100 days. Some even remembered the 1988 strike, the longest in the guild's history at 153 days.

TV writer Tom Fontana, a 45-year industry veteran picketing in New York, just finished postproduction work on his upcoming AMC series “Monsieur Spade.” Given the seismic changes in the industry, from streaming to AI, this work action felt as urgent, if not more so, as any in the guild’s history, he said.

“We are talking about existential threat to the work we do,” Fontana said.

Veteran writer-producer Danny Strong, who shut down his work on the development of several TV projects, said the economic impact of the pandemic kept the WGA from addressing some of the most critical issues in its earlier contract negotiation in 2020.

“The writers very gracefully compromised in 2020 because of the pandemic to not have this discussion and gave it another three years,” Strong said. “I think the union will be more entrenched now because streaming has even gotten that much bigger in the last three years. The financial model for paying writers needs to change because it’s completely out of date.”

The WGA has demanded a range of improvements to its contract to address its members' concerns, including increases in minimum pay, better residuals for streaming and higher contributions to the union's health and pension plan. The union estimates that these proposals would gain writers an extra $429 million a year.

Major studios such as Walt Disney Co., Warner Bros. Discovery and Netflix counter that they are facing their own pressures to cut costs in the face of huge debt levels, a possible looming recession and general uncertainty about the future of the streaming business.

Warren Leight, a former executive producer for “Law & Order: SVU” who served as strike captain in New York, said the current practice of creating "mini-rooms," where small teams of writers are hired to hash out a show before it goes into production, is already having a long-term negative impact on content. Those mini-room writers may never get on set of see the show in production.

Leight said in his last term as showrunner for “Law & Order: SVU” he was alarmed to meet writing job applicants who worked on several shows but never set foot on a set. “Imagine somebody hires a chef who’s never been in the kitchen," Leight said. "It doesn’t work. You have to understand what production is.”

Outside the Warner Bros. lot in Burbank, Jackie Penn, who has previously written for a Disney+ dramedy series and a CW show, was among some 200 writers protesting. Penn said she has been out of screenwriting work for a year and has had to find work outside of the industry, tutoring for Los Angeles Unified School District schools.

“I’m trying to help my husband pay bills too,” said Penn. “It’s hard; in L.A. the cost continues to rise and our pay isn’t meeting the cost of living here. ... For writers of color, women, marginalized voices, if you don't have money just sitting there, you can’t be in this industry anymore if you can't afford to be here."

While writers say the stakes for their livelihood are existential, the entire entertainment industry, which is still struggling to rebound from the impact of the pandemic, stands to take a hit if the strike drags on for weeks or months.

The strike has already caused late-night talk shows, including “The Late Show With Stephen Colbert,” “Jimmy Kimmel Live!" and “The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon,” to pause production, and scripted TV series like HBO's “Hacks" and “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” which are currently shooting, could be close behind. "SNL" confirmed Tuesday that it is going dark amid the strike.

A protracted shutdown in production could hurt not only those who work directly in film and TV but also the many others who help service the entertainment industry, including drivers, dry cleaners and caterers. By some estimates, the last writers' strike cost the local economy more than $2 billion.

“Los Angeles relies on a strong entertainment industry that is the envy of the world while putting Angelenos to work in good, middle class jobs," Mayor Karen Bass said in a statement Tuesday. "I encourage all sides to come together around an agreement that protects our signature industry and the families it supports.”

California Gov. Gavin Newsom, in an interview with MSNBC's Stephanie Ruhle at the Milken Institute Global Conference, warned of the wider economic damage the strike could wreak.

"It has profound consequences, direct and indirect," Newsom said. "Every single one of us will be impacted by this. We're very concerned about what's going on because both sides are dug in. And the stakes are high."

For now, the WGA has the support of the other Hollywood unions, including SAG-AFTRA (which reps actors), the Directors Guild and the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, which represents crews, though it's possible such solidarity could begin to fray as the strike grinds on.

At the Disney picket line, Jay Leno pulled up to the Alameda gate in a Tesla to hand over two boxes of Randy's Donuts.

Speaking outside the Sony lot, Moisés Zamora, showrunner on the Netflix series "Selena," said that, even if it is resolved relatively quickly, the strike is certain to deal a blow to many writers' incomes.

“Even if we come to a deal in the next weeks, it’s going to take months for things to pick up," Zamora said. "It’s going to be very difficult. I’m lucky I have a partner who I can count on, but a lot of other people don’t.”

Whatever short-term pain the strike may bring, Zamora said it is necessary to create a fairer compensation structure for writers in Hollywood's streaming economy.

“Being a writer sounds glamorous and privileged, but if we can’t make a living, or even be the middle class, something is very wrong with the system, especially during peak TV," Zamora said. "Executives are making millions. Everybody likes a really good story. We just want to be paid for it.”

Times staff writers Stephen Battaglio, Meg James, Laura J. Nelson, Mark Olsen, Stacy Perman and Jonah Valdez contributed to this report.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.