Military leader from Green Bay records 'Dover Road,' song about PTSD and part of his efforts to get veterans help

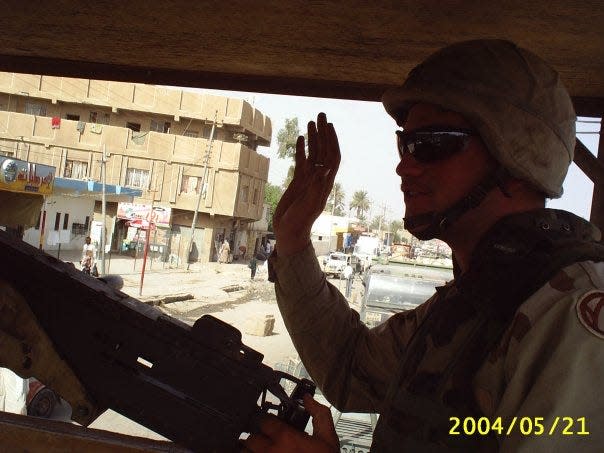

GREEN BAY - Dover Road, the alternate supply route soldiers would take in Iraq, buzzed with a quiet terror for Command Sgt. Maj. Michael Aschinger, who regularly heard fellow soldiers mutter aloud, "I hope I don't die today."

The sign on a bare brick wall reading "IS TODAY THE DAY" made that hope all the more profound and serious. Aschinger would move with his assistant gunner to protect convoys up and down Dover Road, swallowing dread and worry as mortars and roadside bombs jarred soldiers out of contemplation and into certain peril.

"I've lost friends and veterans. I've had friends and veterans, some great ones who've had real crises. I've had to intervene in more crises than I would like, but I always saw that people really don't want to die," said Aschinger, of Green Bay. "But it hurts. All of a sudden, Dover Road went from being about an alternate supply route, Dover, to this road that we're on afterwards."

During his first tour in Iraq in 2004, Aschinger wrote what would become a song he sang often to fellow soldiers and veterans, named for the road that instilled in so many a sense of anguish and fear. "Dover Road," for Aschinger, became a way to keenly articulate the pain of suicidal ideation, post-traumatic stress disorder and grief he and so many of his fellow men and women of arms endured, crossing roads into an ambiguous brutality. It also allowed him to express his deep respect and love for the Iraqi people he came to know during his tours.

"As I started to play the song throughout the years, I realized I wasn't just playing it about being afraid on Dover Road, but on the follow-up roads. I'm proud to say that I have PTSD. I'm allowed to say that, even as a senior leader in the military, and that has had its own struggles over the years," Aschinger said. "Music has been such a way to express the pain involved, the anxiety, but also the healing that can come."

Aschinger has served in the U.S. Army Reserves for 14 years. As the command sergeant major, he's the senior enlisted adviser to the commanding officer, where he teaches a group of high-ranking instructors across the western U.S. within his area of operations.

For the last six months, he's also worked as the security manager for HSHS hospitals in east Wisconsin, covering St. Clare Memorial Hospital in Oconto Falls, St. Vincent and St. Mary's hospitals in Green Bay, and St. Nicholas Hospital in Sheboygan.

Music isn't the only road Aschinger has taken to uplift mental health awareness in veterans. He also pursued a master's in clinical mental health counseling and counseling psychology, in order to commit his attention to being a suicide prevention instructor both in the military and civilian world.

He trains QPR (Question, Persuade, Refer) suicide prevention to civilians and non-traditional suicide prevention in the military, but more than what education can offer, Aschinger allows himself to get choked up when describing stories from wartime. As important as it is to give people the toolbelt to assist in suicide prevention, Aschinger wants to serve as a role model for being emotionally available, open and honest about his personal struggles.

Survivors guilt, PTSD, panic attacks spur military leader to seek therapy

When Aschinger traveled to Kansas City, Missouri, for a 10-year reunion marking his first tour in Iraq, he described himself as "the happiest guy in the world" before he entered the room. But when he saw the familiar people from his tight-knit group, he noticed a collective sorrow etched into their faces.

During the reunion, his first sergeant from that period presented a piece of shrapnel from an exploded truck. The crowd fell silent as the story behind the physical object bloomed into a reckoning before them.

People in the room remembered the very serious incident the piece of metal represented: a vehicle-borne IED triggered on one of their trucks. They were sure they would lose one or two soldiers from the severity of the explosion, although both fortunately survived.

Between seeing the physical evidence of this traumatic event and the way his heart broke upon seeing his buddies in pain, Aschinger said he went into a dark place that lasted months. It wasn't until his wife brought up his mood with him that he understood the extent to which he needed therapy.

"I realized I needed to talk to a therapist. I'm walking around with survivor's guilt and, more than that, being-successful guilt. Suicide affects the veterans' community greatly because of the closeness that you gain with people," Aschinger said. "And so, when you hear that you lose a veteran, even if it's 15 years after the fact, it's like losing them 15 days ago."

Aschinger has lost many people in his life to suicide, including his father, who worked for the Los Angeles Police Department and died in 2010. He watched his father choose unhealthy coping mechanisms to deal with his PTSD until succumbing to his pain. Therapy and reaching out for help didn't seem like an option.

Aschinger wants to bust the myth that reaching out for professional help has anything to do with weakness.

That said, fears of the conversation not being confidential and the perceived difficulty of veterans finding a provider often stand in the way of getting care.

"PTSD, unfortunately, is kind of a high anxiety, which usually leads to avoidance of behaviors. And because of that, the condition doesn't lend itself sometimes to seeking help," Aschinger said.

There was a time not so long ago when Aschinger thought he was having heart problems. He'd experience a compression in his chest, shortness of breath and aches. Test after test showed his heart in tiptop shape, until one physician correctly identified his struggles for what they were: symptoms of a panic attack.

Now, he and his wife both know what they're looking at when panic attacks arise, and they can walk him down from his attack. Aschinger emphasized the importance of veterans educating themselves on mental health conditions. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs lists some of the more common mental health conditions from which veterans can struggle, including anxiety disorders, depression and PTSD.

"I made it to the highest rank in the Army, am a highly decorated soldier, and I have panic attacks," Aschinger said. "Learning all these things about persistently chronic conditions leads to a really high quality of life."

Veterans can get help from other veterans, and other resources

On one particularly sad night, Aschinger posted the song "Save Me," by Jelly Roll to his Facebook page. He wasn't experiencing suicidal ideation, but he was in a low state. Almost immediately, his friend Facebook-messaged him and said, "Call me right now."

"I ended up having a long conversation with him and it really helped me. He took it upon himself to make me call him just because he had the slightest inkling that something might not be OK," Aschinger said.

Sometimes, Aschinger said, that's exactly what's needed: A phone call when someone suspects even the "slightest inkling" of a problem.

But when friends aren't enough, Aschinger says there are tons of resources for veterans out there he strongly recommends. He suggests the following:

Stop Soldier Suicide provides safe, confidential care through mental health support, education and training, alternative therapies, and resources and referrals.

Vet Centers are local, fully confidential and free for veterans seeking assistance and help. Aschinger said he's had plenty of "lunch dates" with soldiers through the Vet Center who needed a break and someone to talk to.

Military OneSource provides a number of free appointments to veterans, and there's a facility in the Green Bay area.

Navy Seal Foundation provides critical support for the warriors, veterans and families of Naval Special Warfare.

The Gary Sinise Foundation works with disabled veterans, children of fallen soldiers, veterans' mental wellness, community and education, and first responders.

Tunnels to Towers provides mortgage-free homes to Gold Star and fallen first responder families with young children, builds custom-designed homes for catastrophically injured veterans and first responders, helps to eradicate veteran homelessness, and respond to major U.S. disasters.

MORE:As domestic violence in Wisconsin surges, shelters unable to keep up with need

MORE:Mental illness is delaying young adults from entering the workforce. A new program can help.

Natalie Eilbert covers mental health issues for USA TODAY NETWORK-Central Wisconsin. She welcomes story tips and feedback. You can reach her at neilbert@gannett.com or view her Twitter profile at @natalie_eilbert. If you or someone you know is dealing with suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or text "Hopeline" to the National Crisis Text Line at 741-741.

This article originally appeared on Green Bay Press-Gazette: 'Dover Road': Green Bay veteran uses music to talk about mental health