The wrong man accused of a crime? Then, in a Hitchcock film — and now

One of Alfred Hitchcock's least-known movies may be, in 2023, one of the most timely.

"The Wrong Man" (1956) centers on a classic Hitchcock theme — the innocent man, falsely accused. It was the setup of some of his most famous thrillers: "North by Northwest," "The 39 Steps," "Saboteur," "Strangers on a Train."

Only this time there was a difference. The story was true.

"I really thought it was one of his more underrated films," said Jason Isralowitz, a North Jersey lawyer who has taken a second look at the film, and the real-life case that inspired it, in a new book, "Nothing to Fear: Alfred Hitchcock and the Wrong Men" (Fayetteville Mafia Press, available Jan. 14, $24.99).

He isn't alone in his admiration. French New Wave director Jean-Luc Godard was also a fan. Martin Scorsese cited it as an inspiration for "Taxi Driver."

But Isralowitz, with his legal background, has a special set of tools for examining this story of justice miscarried — a story that anticipates all the cases of judicial error, from Rubin "Hurricane" Carter to the Central Park Five, that keep groups like The Innocence Project working overtime.

"It tells a true story that I think taps into this universal nightmare of what it's like to be falsely accused," said Isralowitz, who grew up in Englewood and Fair Lawn.

"Most of Hitchcock's other mistaken-identity films emphasized escapism and adventure," Isralowitz said. " 'The Wrong Man' is very different. And Hitchcock set out to stay true to what actually happened in the case, in a way he had never done before. There was a tremendous amount of research the filmmaking team did."

True story

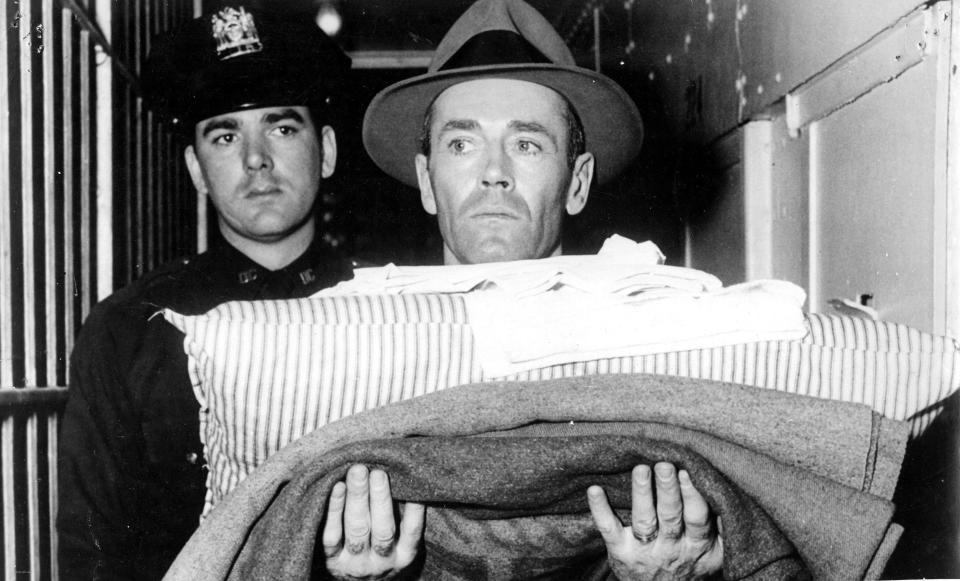

Christopher Emanuel "Manny" Balestrero, played in the film by Henry Fonda, was a real guy. Ordinary — as Hitchcock heroes tend to be. Struggling musician, with a wife and family.

On January 13, 1953, he went to his Prudential Insurance office in Queens to seek a loan. Employees identified him as the stickup man who had twice held up the office the previous year.

The ensuing four-month nightmare, which saw Balestrero arrested, arraigned and (briefly) imprisoned, and led to his wife's nervous breakdown, was the subject of a 1953 Life magazine profile, "A Case of Identity." The low-key, realistic black-and-white film that Hitchcock derived from it echoes that theme. Or appears to.

This was a freak accident. A case of mistaken identity. What are the odds that two men, nearly alike in appearance — one an upright family man, the other a career criminal — would be running around Queens at the same time?

"The Wrong Man's" famed, climactic set-piece appears to double down on this. Fonda, at the end of his rope, is shown praying. Dissolve — and, chillingly, we see the right man (Richard Robbins) on the street, walking toward the camera, until his face superimposes on Fonda. Lookalikes!

Second glance

That, anyway, is how most people remember the scene. But in fact, Isralowitz said, the two guys don't look so much alike. Nor did they, in real life.

"When you go back to the press in 1953, all the major papers referred to them as doubles, twins," he said. "There was this narrative that the state put out to explain this tragedy — that this was a sincere series of eyewitness mistakes."

What this really was, says Isralowitz, was a case of official rush to judgment. Of a kind that is very much in the news today.

"I saw a connection between the case in the movie, and the modern innocence movement," Isralowitz said. He'll be talking about that, and much else, when he introduces a Jan. 24 screening of "The Wrong Man" at New York's Film Forum (8:10 p.m.).

"The innocence movement really took off in the late '80s with the DNA revolution, which has led to the exonerations of so many innocent people," he said. "After those exonerations, criminal justice experts would go back and analyze what led to those wrongful convictions."

Unreliable eyewitness testimony, for starters. Witness-leading. The cherry-picking of facts, to fit a pre-determined theory. "I think those problems are all on display in 'The Wrong Man,' " Isralowitz said.

Something new for Hitch

Though Isralowitz now lives in Summit, with a practice in Manhattan, he was originally from Queens — like Balestrero. He has a natural connection to this case. And he had been intrigued by Hitchcock ever since he saw "Psycho" as a student at Boston University. "They screened it at Halloween," he said. "I can still hear the students screaming."

There is, of course, no shortage of books about The Master of Suspense. But "The Wrong Man" was not highly regarded by many, including Hitchcock himself. It made only $2 million (compare that to "Psycho's" $50 million) and was generally viewed as an odd experiment by a director whose real strengths lay elsewhere.

That, too, is a rush to judgment, Isralowitz believes.

"I was really struck with how timely the movie feels today, even though it was made in 1956," he said. "I found it to be a haunting story of a miscarriage of justice. In the 1950s, the American legal system had not really reckoned with the issue of wrongful imprisonment in any meaningful way."

The NYPD, in the 1953 Balestrero case, had a working theory: that the same man was responsible for a series of holdups — some 40 — in the Jackson Heights area.

And in fact they were right. It was the same man who had held up liquor stores, drug stores, delis, and Prudential Insurance on two occasions. But that man was not Balestrero.

"There were substantial reasons for the police to doubt Manny's guilt from the beginning," Isralowitz said. "They ignored his alibis — and he had very strong alibis."

Close to the bone

This was a very personal story for Hitchcock.

The fear of police, and of false arrest, was one of his key phobias, though his films often dealt with it in a tongue-in-cheek manner. One of his oft-repeated stories is being sent, as a five-year-old, to the police station with a note from his father. "The chief of police read it and locked me in a cell for five or ten minutes, saying 'This is what we do to naughty boys,' " Hitchcock recalled.

Here, in "The Wrong Man," was a story of an actual man living his worst nightmare. Hitchcock wanted to make it ring true. He gave the film an almost documentary realism — disappointing to those who were expecting a typical, glamorous Hitchcock thriller.

He shot in actual locations in Queens and Manhattan, including The Stork Club where Balestrero played bass in the band, and The Victor Moore Arcade (named after the once-famous comic actor) where the insurance company was located. He filmed in Balestrero's real-life prison cell, and courtroom.

"The Wrong Man's" two lead actors, Fonda and Vera Miles, went to Florida where the real Balestrero and his wife had relocated. "He showed him how to hold the bass," Isralowitz said.

Called into question

Most subtly and damningly, Hitchcock showed the judicial system in a realistic — and harsh — light.

Not evil. Not brutal, exactly. But relentless. Inhuman. "What makes the whole ordeal even more dreadful is that when he protests his innocence, all the people around him are very nice about it, saying, 'Yes of course!' "Hitchcock said.

Though the film's defense attorney (Anthony Quayle) calls it a "tragic case of mistaken identity," what we actually see in the film is problematic behavior by authority — at a time when few moviegoers were prepared to see the legal system called into question. In this, as in much else, "The Wrong Man" was ahead of its time.

"As you watch these events unfold in the film, Hitchcock is showing the police and the prosecutors moving through their routines like they're on an assembly line," Isralowitz said. "This was not an attempt to frame an innocent man. But you get the sense that they're rushing Manny through the system recklessly. This is not a movie that exonerates the police, if you will."

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: 'The Wrong Man,' a Hitchcock flop, gets life anew with this book