Wrongful arrests, court slowdowns: Despite complaints, eCourts expansion moves forward

Amid all the confusion on that still spring evening in late May, one thing was clear to Rotesha McNeil as she sat handcuffed in a deputy’s cruiser: There had to be some mistake.

Yet there she was, headed to the Johnston County Detention Center hours before dawn broke in Clayton, in custody on an arrest order that wasn’t supposed to exist.

Kevin Spruill was similarly baffled when Zebulon police pulled him over in March on an outstanding warrant — supposedly for obtaining property under false pretenses. He’d been arrested on that felony charge a few weeks earlier, appeared before a judge, posted bond and was prepared to show up for court again in three days to insist on his innocence.

But the warrant — for some reason — remained. Hands cuffed, he awkwardly thumbed through his phone to show his release paperwork to the Zebulon officer, who eventually let him go. But when he showed up for his next court date, he was shocked when he was detained yet again.

On paper, these two cases don’t appear to have much in common. They involved different charges. They originated from different times and with different law enforcement agencies.

But McNeil and Spruill have signed on — along with a growing list of others — to a potential class action civil rights lawsuit against the developers of a $100 million-plus software package meant to drag North Carolina’s archaic court system into the online age.

Rather than improve the operations of the state courts, the lawsuit alleges, the rollout of the electronic system designed by the Texas-based Tyler Technologies Inc. has wrongfully landed people in jail.

And as the courts ready for a significant expansion of eCourts on Oct. 9 to Mecklenburg County, the highest-volume courthouse in the state, plaintiffs in the lawsuit aren’t the only ones concerned.

At least two district attorneys have urged court administrators to order an independent review of the launch and its ongoing problems. And some defense attorneys struggling with the system in Wake, one of the four pilot counties where the eCourts case management system rolled out in mid-February, say its disruptions and slowdowns are putting the public’s constitutional rights at serious risk.

“If DoorDash has a bug in the system, you might not get your potato chips,” Steven Saad, a former prosecutor who now runs a private defense practice, said. “If there’s a bug in this system, people get arrested. They lose their licenses.”

Tyler Technologies referred questions about the rollout of its eCourts software to the N.C. Administrative Office of the Courts, the agency managing the transition.

“As a standard practice, we do not comment on pending litigation,” Tyler spokesperson Karen Shields said in an email to The N&O in late August.

Tyler asked a federal judge to dismiss the suit in a filing Sept. 20, arguing the case contained “no plausible factual allegations” against the company, which has “no legal duty to protect plaintiffs” and is not responsible for the software’s daily use.

AOC declined repeated requests over four weeks from The News & Observer and The Charlotte Observer to make Director Ryan Boyce available for an interview.

In emailed responses to a list of questions from the McClatchy newspapers, a spokesperson denied eCourts caused any erroneous arrests. And although he acknowledged “intermittent issues” with performance, he contends the rollout has improved court operations and increased transparency for the public.

“The comprehensive scope of the eCourts project in North Carolina connects law enforcement, courts, and the public, to move our state from a laggard to a leader with long-term benefits for a generation,” AOC spokesperson Graham Wilson said in an email to The N&O Sept. 1.

But that lurch toward a more connected court has come at a cost, argues Zack Ezor, an attorney with the Triangle-based law firm that filed the federal civil rights suit — one the state has so far failed to reckon with.

“There’s just been a tremendous callousness from the powers that be about the sort of collateral damage that it’s caused,” Ezor said.

Vision of a ‘virtual courthouse’

Moving 100 county courthouses from a system of paper records and decades-old physical mainframes is, suffice it to say, a complicated job.

When fully rolled out statewide, eCourts will be the cloud-based backbone of court operations. It’s how cops know who to arrest. How attorneys will access documents. How judges will sign and issue orders. The system must withstand a tremendous volume of court activity across the state, especially in counties like Wake, which alone processes more than 10,000 civil, criminal and infraction cases filed every month.

For the public, it will mean the ability to file, look up and view court records from anywhere with an internet connection — without having to drive to a courthouse.

The process started in earnest five years ago, when the Administrative Office of the Courts held meetings across the state to figure out what courthouses actually wanted from such an upgrade. After months spent evaluating proposals from vendors — and with the unanimous support of a committee of court officials from across the state — the AOC in mid-2019 signed a 10-year contract with Tyler Technologies Inc., a publicly traded firm headquartered in Plano, Texas. The initial cost: $85 million.

The suite of products the state purchased would help create “a virtual courthouse, where paper processes are a thing of the past and efficiencies are gained by Judicial Branch offices across North Carolina,” AOC interim Director McKinley Wooten said at the time.

It was the company’s largest-ever “software-as-a-service” deal — and the most populous state its Odyssey software had handled yet, according to a Tyler press release. An expansion of the contract less than a year later increased the state’s price tag to about $100 million.

In a statement to The N&O in early September, an AOC spokesperson noted that the four-county pilot has spared the public from courthouse trips and has saved “more than 1.5 million pieces of paper by processing an average of 10,000 remote records searches per day and nearly 300,000 total electronic filings over six months.”

But in more than seven months of operation, eCourts critics have been persistent and numerous.

Local news stations noted problems with the publication of Social Security numbers and other private information, the execution of expunctions — even the validity of divorces. Top state House Democrat Robert Reives, a practicing attorney, called for an inquiry into the launch before later backing down.

AOC leaders, however, have pushed back against those criticisms — at times forcefully — in letters and prepared statements in which Boyce has sought to “respectfully refute significant misinformation.”

Then came the civil rights lawsuit in May, in which two residents of Wake and Lee counties alleged that not only were their arrests violations of their civil rights, but the mistakes that landed them in jail were “foreseeable.”

By the time the case winds its way through federal court, however, attorneys involved with the suit predict the list of plaintiffs will grow much, much larger.

Wrongly detained, strip-searched

Rotesha McNeil was almost home when she saw the blue lights of a Johnston County deputy’s cruiser in her rearview mirror just after midnight on May 30.

It was supposed to be a quick trip up the road to pick up her husband after his late-night shift as a truck driver — she hadn’t even bothered to wake her teenage daughter before she left.

After she stopped, the deputy told her the light that was supposed to illuminate her license plate was out. But after running her name, he and a Clayton police officer who pulled up to assist said she had warrants out for her arrest.

The arrest orders originated from charges years earlier over her expired registration and suspended license. She’d hired a lawyer, paid the fines and her attorney had sent her paperwork after resolving the case.

The deputy was sympathetic, she said. He let her sit, handcuffed, in the front seat with him as he pointed to the readout of the electronic warrant system on his cruiser terminal.

“He turned the screen to me and showed me where it said two warrants for your arrest, and they said ‘failure to appear in Wake County,’” McNeil said.

At the county detention center, staff took her mugshot. She was asked to strip while a female detention officer conducted a cavity search.

“I told her: I feel like you just raped me,” she said.

As the hours ticked by, she shifted back and forth from a holding cell, where she paced alone, to an area nearby where she made frantic phone calls to her lawyer and her husband, who had been working to reach a bondsman.

He found one early that morning, and secured his wife’s release for $300. But McNeil wasn’t done.

That same morning, they drove to Raleigh to confront the clerks at the justice center downtown, who McNeil said confirmed a mistake with the warrant for her arrest.

“The girl told me, ‘Oh, it’s supposed to have been taken off,’” she said. “But no one took it off.’”

‘I figured it was a mistake’

The state’s case against Kevin Spruill was, by all accounts, a strange one.

A few weeks after he bought groceries at a local Food Lion in June 2022, an officer came knocking on his door in Morrisville asking him to come downtown to help with an investigation. He said the officer didn’t provide many details.

Spruill declined.

“I didn’t hear anything else about it,” Spruill told The N&O. “I figured it was a mistake.”

Almost eight months later, he was pulled over in Durham while heading home from a friend’s house. The deputy initially told Spruill he stopped him because his license plate frame obscured his tag. But about 20 minutes later, the deputy told Spruill there was a felony warrant for his arrest — a woman he’d never met reported that her bank account had been fraudulently used to purchase $105.92 worth of groceries.

“At that point, I was extremely confused,” he said, noting that he made the purchase with his own debit card, drawn from his own checking account.

Spruill was handcuffed and booked on one charge of obtaining property under false pretenses at the Durham County Detention Center, where he posted bond and was released the same night.

He ended up in handcuffs twice more — once when he was stopped in Zebulon and again when he showed up to court for the case in question — and said he only managed to avoid jail time because law enforcement took him seriously when he showed them his court paperwork.

“At that point, I was like: You gotta be kidding me,” Spruill said. “We just did this a couple of days ago.”

Spruill said court officials at the time weren’t clear on why the warrant kept popping up, again and again.

“They were saying that my file didn’t upload into the system for whatever reason,” Spruill said. “I just assumed it got lost in the shuffle. That’s all the information I got.”

Ezor, one of the attorneys handling the potential class action suit against Tyler Technologies and law enforcement officials, said he’s talked to dozens of potential clients across the state who have similar stories. Two plaintiffs were named in the original complaint filed in May, while others — like Spruill and McNeil — will be added in the coming weeks, Ezor said.

Many of his new clients were forwarded directly from frustrated defense attorneys, he said.

“In the time that we filed it, we have just heard from many, many, many more people who we’ve been signing up in the interim as co-plaintiffs in this case,” Ezor said. “The stories are pretty disturbing.”

In response to questions from The N&O about the cases in the lawsuit and other wrongful arrests, an AOC spokesperson said the agency “has investigated these and similar claims and found no instance when an eCourts software defect resulted in a wrongful arrest or incarceration.”

The agency was unable to say how many of these claims they’ve investigated, the spokesperson said, “as reviewing reported issues is a core function of the NCAOC for eCourts and legacy systems that our teams conduct on a regular basis.”

“In the lawsuit referenced in (The N&O’s) question, AOC is aware of two plaintiffs,” Wilson, the AOC spokesperson, said. “Over one million criminal processes and hundreds of thousands of electronic filings have been processed in eCourts applications.”

Human error, or tech error?

Wake County District Attorney Lorrin Freeman said she’s aware of cases where people were wrongfully arrested after the pilot launched. Such arrests happened occasionally before the launch, she said, because of human error.

But the change in how the new systems operate increased the likelihood of those errors — at least initially, she said. Where the old system would have immediately recalled arrest warrants when a case was closed, the new system requires clerks to cancel arrest warrants manually in an additional step.

“It was a change in business process. It just took some time for everybody to kind of learn,” Freeman said. “And while that learning process was going on, unfortunately, ones got missed and people got served with orders for arrest that should not have been.”

Once court staff became aware, she said they “jumped on it very quickly” to reduce the risks of more improper arrests. AOC now generates a report that alerts clerks to cases that have been closed out but still have active warrants in the system, she said.

Freeman said errors like those described in the civil rights lawsuit are no longer happening at the same frequency. And even when the problem was at its peak, she doesn’t believe it was systemic.

“I don’t have information that would lead me to believe that it was ever really high or that this impacted a lot of people,” Freeman said.

DAs want independent review of rocky digital courts launch. Why that looks unlikely

Part of the value of the federal lawsuit, Ezor said, is to reveal the causes of these mistakes and how widespread they’ve really been.

“Our job is actually to figure out both what’s going on with the technology, but then also, where some of the gaps might have been in training,” Ezor said. “Because Tyler’s job was to deliver a successfully functioning digital case management system and warrant system and not to simply just throw the keys to the car on the ground and hope that the person figures out how to drive.”

Ezor anticipates more clients will sign onto the suit, which has not yet been certified as a class action by a judge, when eCourts goes live in Mecklenburg County.

But beyond the prospect of wrongful arrests, he’s also worried about the basic operations of the courts in the state’s second most populous county.

“Everything’s just going to slow way down. And I don’t think they’re ready,” Ezor said.

Slowdowns and shutdowns

Those slowdowns are still on the minds of district attorneys in the original pilot counties, seven months after the eCourts launch.

“The bigger issues that we have right now are some of the inefficiencies in the system that aren’t getting better,” Freeman told The N&O in late August. “And I would have expected them to get better by now.”

She acknowledged that there’s been significant improvement in the courts’ day-to-day operations, compared with the days post-launch. And she stressed that “the court’s business is getting done.”

“There’s no way, from my perspective, if people are being honest, that they can say that we’re not running a lot more efficiently today than we were in March,” Freeman said.

But despite seven months of operation, she said the courthouse is still not running like it was compared to last year.

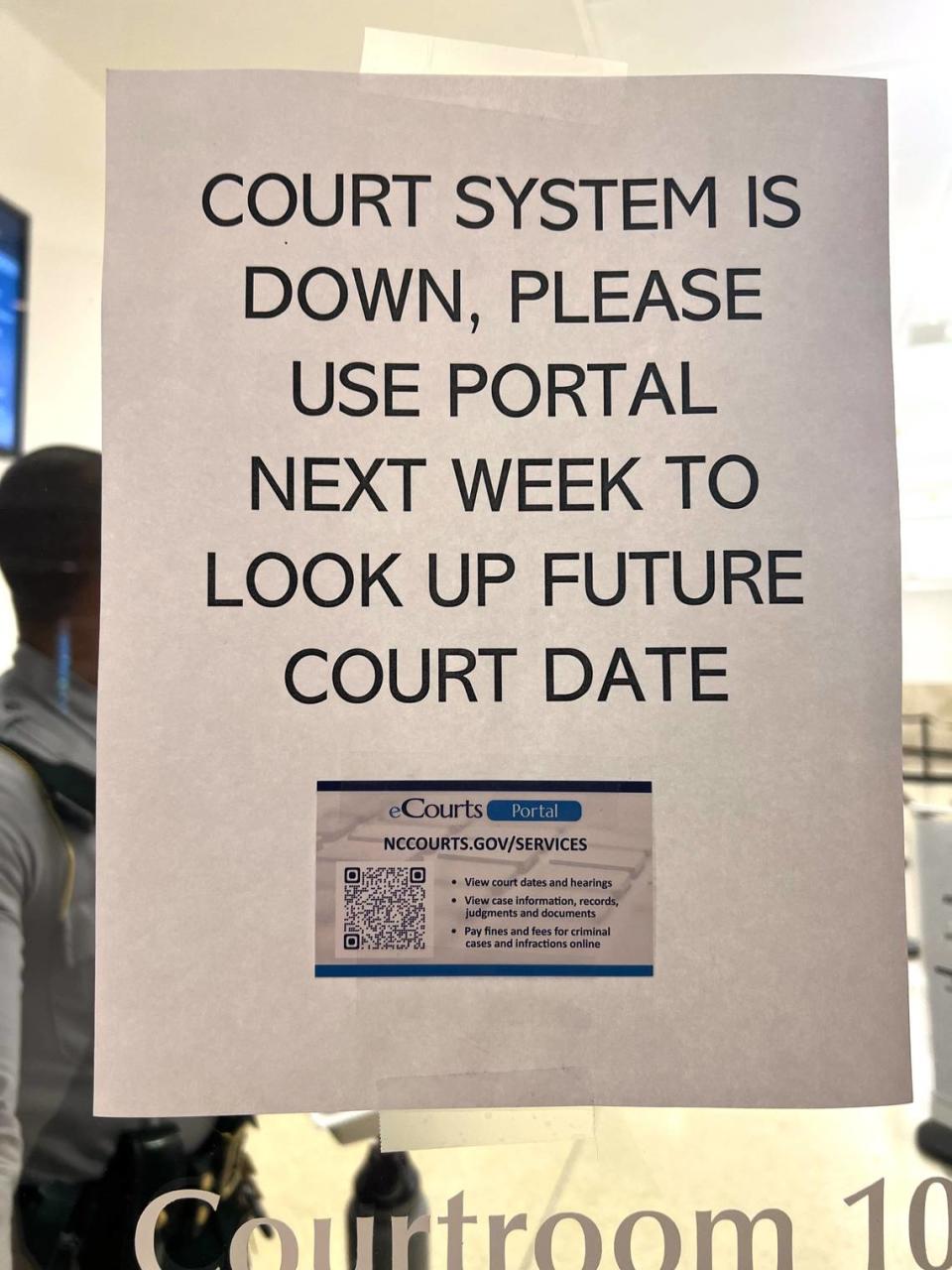

Most notable, she said, is the slow operation of eCourts and that it goes offline “with some regularity.” Those problems aren’t just minor inconveniences for attorneys, clerks and judges — they can frustrate the public too.

“We’re totally dependent on it, right? So you got a courtroom full of people, and I can’t pull up a single case because the system’s down and everybody’s just sitting there,” Freeman said. “How does that instill confidence?”

Case in point: The system froze and locked out users in one Wake County courtroom on Sept. 13, bringing proceedings to a grinding halt. Freeman said she had to send about 60 people waiting for resolution on their cases home — forcing them to come back to court another day.

That means more time off work. More arrangements for child care. More time spent with a pending charge impacting jobs, housing — even driver’s licenses.

In Johnston County, the second-largest court system in the pilot, District Attorney Susan Doyle said eCourts “is still plagued with problems.”

“I have sent numerous videos to AOC and Tyler representatives showing them how slow the system is and how that prevents us from working cases efficiently,” Doyle wrote in an email to The N&O on Sept. 14. “I sent so many emails and videos that Tyler installed a program on my computer that enabled them to watch what was happening in real time as I attempted to access cases.”

And she’s not alone, she said.

“Every single user in pilot county district attorneys’ offices experiences this same thing,” Doyle wrote. “Unfortunately, there have been no solutions.”

For their part, state court leaders have acknowledged the rollout “has not been easy” given the monumental nature of the transformation. But in a response to questions from The N&O, an AOC spokesperson said eCourts has seen improvement in both software and infrastructure performance during the pilot phase.

“We’ve heard from attorneys and court officials that eCourts has made significant progress on system stability and latency and improved the operations of the courts,” a statement from Wilson said in an email Sept. 1.

When The N&O asked AOC to provide examples of that feedback from users in the state’s pilot counties, the agency shared a letter from State Bar President Marcia Armstrong, who wrote to her organization’s members in April that there were still “issues to address and processes to smooth out.”

“The State Bar recognizes that these growing pains can be frustrating, but also firmly believes that once the implementation is complete, the new system will revolutionize our court system and promote much greater access to justice for everyone in North Carolina,” Armstrong’s letter said.

She told The N&O by email that the staff at her firm in Johnston County has found the eCourts system “helpful.”

“It is very convenient to file and retrieve documents from the comfort of our office,” Armstrong wrote on Sept. 15. “Recently, I heard one of our paralegals let out a ‘yahoo’ when she did not have to weather a storm to go to the courthouse to file a document.”

Johnston Clerk of Court Michelle Ball said, at this point, her county “is having a great experience,” with eCourts.

It hasn’t been easy, and there are more mountains to conquer, she said, but over time they’ve improved the system — even winning some early critics over.

“Was it easy? No,” she said. “Was it doable? Yes.”

As one of the pilot counties, she said, part of their role was figuring out and improving the system for the rest of the state.

Doyle disagrees with AOC’s assessment that eCourts has made “significant progress” on slowdowns and downtime since launch.

It’s not designed to handle the volume she and other prosecutors see in some of their courtrooms “and never will be,” she said. It takes time for the system to load and display individual cases, and she said her attorneys “frequently get ‘kicked out’” of the system, forcing them to reboot their laptops to continue working.

And such delays require more people to keep court running. Before the launch, she said she’d normally send one prosecutor to district court to handle the day’s cases. Those days are over.

“The system is so inefficient due to the latency and instability that it requires at least two assistant district attorneys to prosecute a calendar now,” Doyle wrote, adding that heavier days in some courtrooms require four prosecutors instead of two.

Some days are better than others, said Suzanne Matthews, who serves as the district attorney for both Harnett and Lee counties, the other two courts in the eCourts pilot. But when the system is “moving like molasses,” she said it’s frustrating for attorneys to plead with judges and the public for patience in court while they access cases.

“Even an incremental slowdown with every case, when you have 600 cases on the docket, that adds up,” Matthews said.

Although Matthews said she expected the system to work better after seven months of operation, she hasn’t given up hope.

“The public has a level of access they have not had in the past,” Matthews said. “That is a huge improvement.”

Cary-based defense attorney Lindsey Granados is the president of the Wake County Academy of Criminal Trial Lawyers. Despite operating now at what she considers “peak efficiency” with the eCourts system, she said her office is still struggling to keep up — and handles far fewer cases than before the pilot.

“Our functionality has been drastically reduced at the expense of our clients’ constitutional rights,” Granados said.

Jobs that used to take 15 to 20 minutes — like excusing a missed court date and recalling an active warrant — can take a week or more in the eCourts system, she said. Attorneys have to manually check and recheck their cases as they wait for judges’ signatures or for court dates rescheduled without notification. She has to hound court officials to find documents and motions that she feels she’s just filing “into the ether” of the cloud-based system.

“Everybody is exhausted because of the extra time that it takes to do anything that we used to do,” Granados said.

She’s spent the last year as part of the county’s eCourts implementation committee pushing for improvements to the system. But she’s concerned that AOC won’t make more serious changes until use of the system spreads to more of the state’s remaining 96 counties.

“Right now, it feels like we’re a four-pilot-county little island in the middle of the ocean,” Granados said. “We’re screaming, and nobody can hear us.”

In his email to The N&O Sept. 14, the AOC’s Wilson said they’ve fixed all of the “high-priority defects” that the agency previously said must be resolved before expansion could continue to Mecklenburg.

Doyle remains unconvinced.

“The eCourts system is absolutely not ready for expansion into other counties,” she wrote in an email to The N&O.

She and the other pilot county district attorneys have created their own list of fixes they believe are necessary before the rollout continues.

“We are hoping to meet with AOC soon to address this list,” Doyle wrote Sept. 14. “However, there is nothing on that list that we have not already expressed concerns about to AOC.”

The chatter around court, criminal defense attorney John Griffin III said, has not been optimistic.

“Everybody’s like: good luck.”

The aftermath

On Aug. 24, almost a full year after a warrant was first issued for Kevin Spruill’s arrest, an assistant district attorney dismissed the case for lack of evidence.

“DEFENDANT PAID FOR THE ALLEGED AMOUNT OUT OF HIS OWN BANK ACCOUNT. WHILE VIC’S BANK ACCOUNT WAS ALSO CHARGED, THERE IS NO EVIDENCE THIS DEF HAD ANYTHING TO DO WITH THAT,” the voluntary dismissal reads.

The dismissal document was logged in the eCourts system at 9:37 a.m., as Spruill waited silently in the gallery of a Wake County courtroom.

After an N&O reporter showed him the new entry, Spruill decided to wait, just to be sure.

About an hour later, his court-appointed attorney appeared with news. In a rare move, the prosecutor wanted to speak with him directly to apologize.

After their conversation, Spruill told The N&O the ADA didn’t have many answers for how the mess occurred. But he was thankful the ordeal was over.

“It’s kind of like fighting in the dark,” Spruill said. “Somebody’s kind of swinging a bat at you, and you don’t know where it’s coming from next.”

Outside the courtroom and packing up to leave, he still carried his paperwork from the first time he was arrested and released — the documents that helped him avoid jail time twice before. Just in case.

“I might just keep it as a memento at this point,” he said with a laugh. “Just as a reminder, man: You can’t take stuff for granted.”

As ready as he is to move on, he still wants someone held accountable. So does Rotesha McNeil. It’s why they both signed onto the lawsuit.

“There’s no part of me that says ‘let it go,’ for the simple fact that I have a mugshot that’s floating around on the internet,” McNeil said. “I can never get my mugshot back.”

As a travel nurse, she worries about how the arrest will look each time she applies for a new hospital contract. When McNeil is asked if she’s ever been arrested, she has to explain what happened in case it comes up on a background check.

She no longer trusts the judicial system. She avoids driving at night, fearful of getting stopped and arrested again.

When her husband needs a ride home from a night shift, she said, he’s on his own.

Reporters Virginia Bridges of The News & Observer and Ryan Oehrli of The Charlotte Observer contributed to this story.