I Wrote One Of The Few Tween Books About Down Syndrome. A Couple Of Sentences May Get It Banned.

The author, Melissa Hart, was inspired by her experiences with her younger brother, who has Down syndrome, to write "Daisy Woodworm Changes the World."

I stood at the front of the library’s presentation room with my whimsical, cat-meme-heavy PowerPoint up on the screen beside me, poised to speak with dozens of homeschoolers. They were on a lunch break from all-day workshops and eager to hear about my life as an author, as well as where they might start publishing their own writing. But before I could pick up the microphone, the children’s librarian beside me spoke into it.

“Those families who requested to leave for this hour should do so now,” she said.

Six kids stood up, their parents beside them, and filed out of the room. I stepped to whisper to the young adult librarians.

“This is because of my character who has two mothers, isn’t it?”

They nodded and rolled their eyes in sympathy. The children’s librarian had read my newest book and tipped off the homeschooling parents. “It’s fine to mention same-sex parents in your story,” she told me with the microphone turned off, “as long as you’re not openly advocating for that lifestyle.”

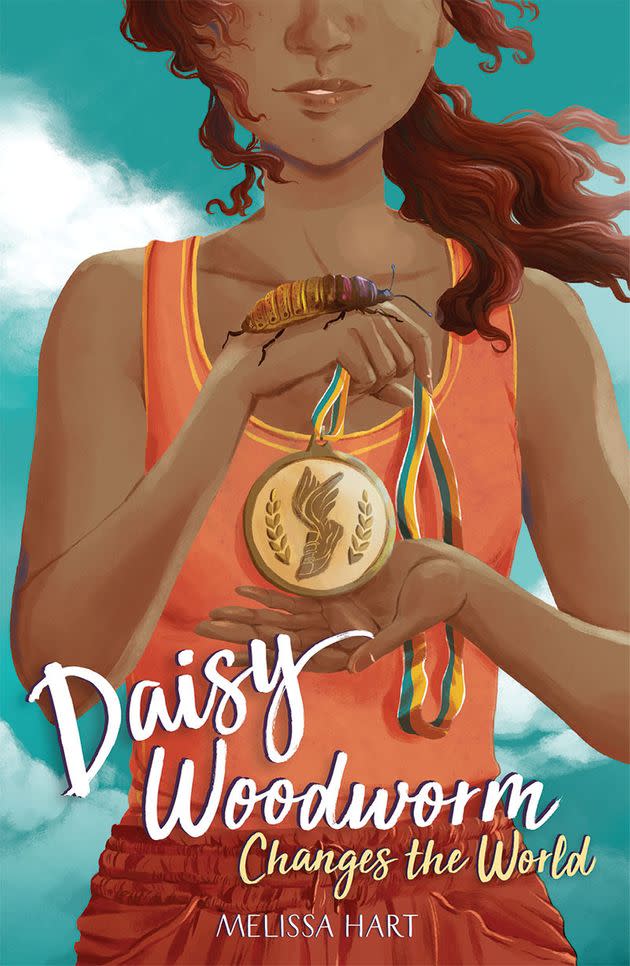

“Daisy Woodworm Changes the World” is my middle-grade novel inspired by my younger brother who has Down syndrome. It features a cast of characters from a variety of races and ethnicities, both neurotypical and neurodiverse, who get a school assignment to change the world. They decide to save the Special Olympics Summer Games in their hometown, which are threatened by a lack of funding.

I can count on two hands the number of novels for children and young adults that feature a main character with Down syndrome. I grew up sharing inside jokes and family camping trips with a sibling with this genetic condition, and I witnessed peers recoiling in confusion and fear because of it. As a result, I’m passionate about representing kids with intellectual disabilities. My characters are empowered and work in conjunction with their neurotypical friends toward a common goal.

That representation, in children’s media, is crucial for the 6,000 people a year born with Down syndrome — people like “Champions” actress and talk show host Madison Tevlin, athlete and inspirational speaker Abigail (“The Advocate”) Adams and fashion entrepreneur John Cronin.

For those who champion diverse books by diverse writers, it’s kids who are suffering the ultimate loss.

But because of a handful of sentences among 281 pages, adults are going to considerable lengths to make sure kids don’t read my newest book. These sentences have nothing to do with Down syndrome. Rather, they belong to the protagonist’s best friend who has — as my brother and I did — two mothers.

Here’s one of the scenes deemed dangerous for young people; in it, the character, Poppy, has just organized a benefit for families affected by a flood in India, inspired by her middle school teacher and track coach:

At intermission, people crowded the dessert table piled with nankhatai and store-bought cookies. Coach Lipinsky walked over to Poppy and her moms. “Spectacular work,” he said and shook Poppy’s hand, and her mothers’ hands too. “I never dreamed, when I assigned this project, that the students would rise to the occasion this spectacularly. You must be very proud.”

“She’s quite a kid.” Poppy’s mom smiled at her.

Her mama clasped Coach Lipinsky’s hand between her own hands. “You’ve helped these kids to achieve amazing things,” she said. “Thank you.”

“Big yikes.” Poppy pulled me toward the coffee station.

“That’s enough emotion for one night!”

To catch you up to speed on the state of book banning in the U.S., a Pensacola school board banned three queer-themed books in February: “All Boys aren’t Blue,”“When Aidan Became a Brother,” and “And Tango Makes Three”—the latter is the 2005 kids picture book based on two male penguins who raised a chick together at the Central Park Zoo.

That same month, a Pennsylvania School District initially reviewed four library books centering queer characters, but community members have now asked administrators to review — and possibly ban — another 60 titles. And in California’s East Bay, parents are challenging Maia Kobabe’s “Gender Queer: A Memoir” as a piece of pornographic indoctrination.

Moms for Liberty, founded in 2021, now has more than 200,000 members in 25 states, and regularly updates the lists of children’s and young adult books they hope to eliminate from schools and libraries. Many teachers and librarians live in fear of becoming a target of this group and others, and of potentially losing their jobs. For those who champion diverse books by diverse writers, it’s kids who are suffering the ultimate loss.

A small section of "Daisy Woodworm Changes the World" mentions a character who has two moms.

I have to admit that I knew ”Daisy” would get banned; I said so on record last year in a CNN article about this issue. So why, if my goal as an author was to offer young readers a story full of vibrant and respectful characters with intellectual disabilities, did I give one kid two moms?

Because many kids have two moms. Or two dads. Or gender-neutral parents.The U.S. Census Bureau recorded, in 2021, 1.2 million same-sex couple households in the country — and 15% of those couples had children. Giving Poppy a couple of mothers felt as natural to me as giving Daisy and her brother, Sorrel, a mom and a dad.

I don’t want kids to grow up, as I did, searching for families that look like theirs in literature for young people and coming up empty-handed. I want to give them stories that reflect the diversity of the world as it really is.

March 21 is World Down Syndrome Day, celebrated by people with this genetic condition and their families and friends. Often, it involves volunteer projects followed by exuberant meals and parties. But I’m willing to bet that most people don’t know this, because many of us don’t know a person with Down syndrome in the world ... or in books.

I had hoped to change this, at least for middle school readers and their caregivers. I never imagined a few sentences about a kid’s two adoring moms would keep “Daisy” from selection in a statewide book battle at which I’d been a guest speaker and judge when my first novel was published. I didn’t realize parents in a library would openly stand up and walk their children out of the room to protect them from the kind of family in which I grew up.

Still, there are moments of hope. Teachers around the country have invited me to speak virtually to their classrooms of middle schoolers. After that whimsical, cat-meme-heavy PowerPoint, I opened up the conversation to Q&A.

“Ask me anything,” I told the kids, determined to answer all of their questions with candor. But so far, no one has asked me about Poppy’s two moms. “It’s a nonissue,” one Washington-based teacher and librarian told me last week. “I don’t think my kids even noticed it.”

Instead, middle schoolers want to know what it was like to grow up with my little brother. They want to know whether he became a YouTube fashion influencer, like the character he inspired in ”Daisy.” They want to know more about Down syndrome, how to volunteer with Special Olympics and how they might change the world, as well.

“Start with writing,” I tell them, offering links to dozens of magazines and contests for young creatives. “Own your story,” I add.

I did, and while I navigate the repercussions with a heavy heart, all I have to do is look at the photo of my moms and my brother on my writing desk to know I made the right choice.

Oregon journalist Melissa Hart is the author of two middle-grade novels: “Daisy Woodworm Changes the World” and “Avenging the Owl,” as well as “Better with Books: 500 Diverse Books to Ignite Empathy and Encourage Self-Acceptance in Tweens and Teens.”

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch.