I wrote a story last year about my adoption. Was some of it possibly based on a lie?

I think there’s a good chance I’ll live the rest of my life without discovering a single shred of information about my birth parents or the circumstances surrounding how I ended up available for adoption as a baby in Korea.

Then again — you never know.

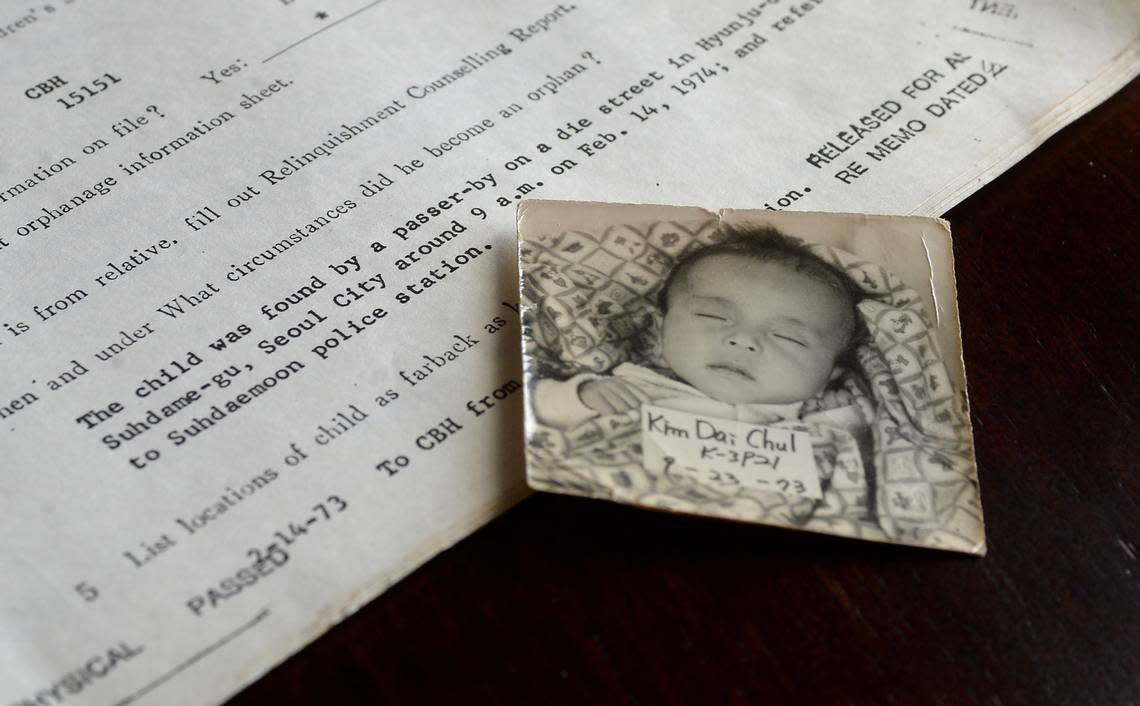

In case you missed it, last October, The Charlotte Observer published a story I wrote after doing several things related to my adoption that I’d almost entirely avoided for the previous 49 years: actually reading through my entire file, seriously reflecting on what I learned from it, talking at length to my parents and my adoption agency, and doing at least some semblance of a birth-family search.

In the days that followed, I heard from adoptees, from adopters, and from friends and family members of adoptees and adopters.

It was overwhelmingly positive, and I was so pleased that my story — my openness about my long-held ignorance-is-bliss attitude, my loving depiction of my adoptive parents, my eventual landing on a powerful empathy for my birth parents — had resonated.

But beyond that, initially, the whole experience led me down no new paths.

Until one day, I received a private message on Facebook from a friend of a friend saying she’d read my article and that we shared similar backstories: Becca Webster and her sister, Dee Iraca, had adoptions papers that purported they were also found on a street in Korea; they too were adopted to the U.S., less than a year before I was; and both now live in the Charlotte area, as well.

She said they’d taken 23andMe DNA tests in 2018 to find out if they were actually twins as their birth records indicated (because they looked so different) — and that three years later their received shocking news:

They’d been matched, through the service, with their birth father.

It’s an incredible story, one that the Observer has published today. It’s not a completely happy one, though, and it underscores the dark side and complicated history of Korean adoptions.

In Dee and Becca’s case, their birth father’s story does not match up at all with the adoption agency’s story of how the girls came to be orphaned.

Meanwhile, Rebecca Kimmel — the woman who played a key role in connecting the sisters with their birth father — has spent years amassing evidence she believes indicates that her identity was switched with another baby after she was orphaned but before she was adopted in order to prevent delays in the process.

Generally speaking, in the U.S. but also around the globe, there’s increasing sentiment that South Korea appears to have routinely arranged and negotiated adoptions in the 1970s and ’80s under false or at least murky pretenses. Just in the past year, adoptees have become more vocal with their criticism of past corruption in South Korean adoption practices, which are believed to have caused countless wrongful parent-child separations and prevented thousands from finding birth families.

The first lawsuit against the country’s government and Holt (which was my adoption agency) was struck down this spring. But more civil action could be coming.

Since writing my story, there have also been multiple feature films released about the darker side of Korean adoptions, including “Broker,” about trafficked adoptees, and “Return to Seoul,” about a reunion with a guilt-ridden birth family. There’s also the documentary film made in South Korea about Becca, Dee and Rebecca that’s mentioned in the story about their recent life-changing experiences, and I recently watched “Found,” a Netflix documentary about three Chinese adoptees who matched as cousins on 23andMe and then went on a journey to try to find parents who had given them up due to the country’s former one-child rule.

Between the growing number of facts and the bits of fiction, it’s a lot to digest.

And my stomach does feel ... unsettled. A lot more so than it did when I wrote my original story last fall.

Because I recently watched Rebecca/Dee/Becca’s documentary with my adoptive parents, and my mom looked a little shell-shocked, and expressed regret that she’d taken the story about me provided by the adoption agency at face value.

Because my paperwork states that I was found on the street in Seoul City, and while that might be true, it also might not be.

Because — and I expected this last fall but I am certain of this now — there’s just no way of knowing what really is or isn’t true about my records at all.

But I followed Rebecca and Dee and Becca’s advice anyway this month and sent a DNA sample to 23andMe. I recently got the results, and while there weren’t any close matches, there’s a second cousin and three second cousins once removed (considerably closer matches than the ones I got through Ancestry, which only came within fourth cousins). Rebecca also suggested that I keep submitting to other DNA databases, join multiple Facebook groups for Korean adoptees, and apply for a “homeland tour” of Korea later this year. So I’m doing all that, too.

It seems awfully unlikely I’ll discover information I don’t already have.

Then again, as Becca and Dee’s story proves: You never know.