WTF is an NFT—and Why Should We Care?

It all started with a cat meme (doesn't it always?). In February, it was reported that a GIF of a pixelated flying kitten with a Pop-Tart for a body and a rainbow coming out of its derrière had sold in a crypto-marketplace for nearly $600,000. Called Nyan Cat, it was created a decade ago but the owner had finally decided to profit from his viral animation. Then the floodgates opened. A video of Lebron James dunking sold for $208,000. The musician Grimes, a.k.a. Elon Musk's partner and the mother of their child X Æ A-Xii, sold ten pieces of digital artwork for $6 million. Most recently, Twitter founder Jack Dorsey sold his first tweet—"just setting up my twttr," published in March 2006—for $2.9 million.

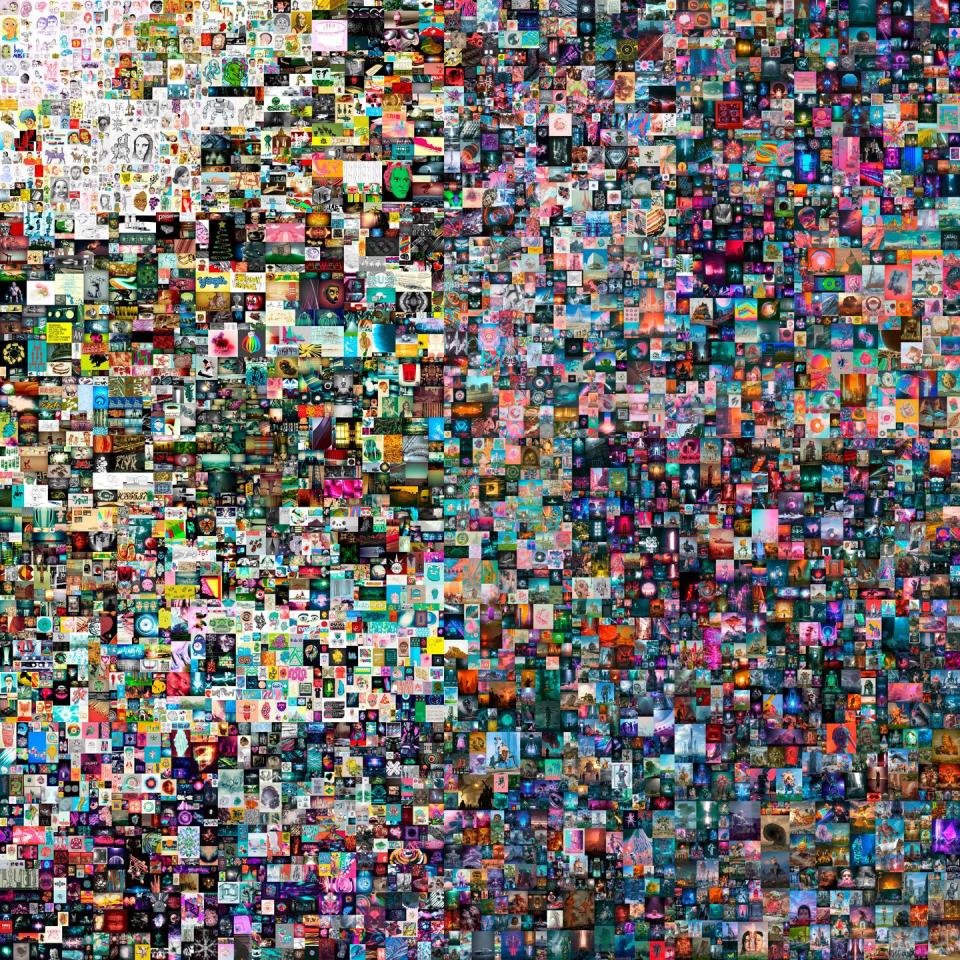

But they were bit players compared to the artist Beeple (né Mike Winkelmann) and his digital work, Everyday: The First 5,000 Days. Composed of the thousands of daily drawings he had created since 2007, the massive mosaic was put up for auction at Christie's and sold for $69 million, putting Beeple in company with Jeff Koons and David Hockney as one of the three most valuable living artists in terms of auction sales.

What unites these things besides their astronomical price tags? That they were sold as NFTs, or non-fungible tokens. They are hardly a new concept—they've been around since at least 2015—but now, most of the world has been force-enrolled into a crash course in NFTs thanks to the incessant stream of news about sale after absurd sale. And the gold rush shows no signs of slowing down.

First, what is an NFT?

A non-fungible token is a digital commodity that has been authenticated with blockchain technology, thereby turning it into a unique, non-interchangeable item. The idea is that unlike an analog asset, like a painting, which is one-of-a-kind by design, digital works can be endlessly duplicated. So the NFT creates a certificate of ownership that proves that it's the original—and only (or limited edition)—version. There will still be copies but whoever buys the NFT can rest assured that they have the authentic one.

Anyone can mint anything into an NFT, be it a photo, video, song, tweet, or GIF, by going through a registration and verification process on a blockchain platform like Ethereum. The commodities are then traded in specialist online marketplaces like Nifty Gateway, Open Sea, and Foundation, where, as a sort of social experiment, the New York Times is currently auctioning off a very meta NFT of a recent column on NFTs. The current bid: 21.00 ETH, or $33,358.29.

By having the power to formally authenticate a piece of digital media, creators have full ownership of their virtual work and a place to monetize it, and can then directly transact with buyers without losing profits to an intermediary. With NFTs, "the concept that creative minds must be paid for what they feed to social digital platforms is finally becoming a thing," says Eloisa Marchesoni, co-founder of blockchain consultancy Blackchain. "Users support other users."

In the last year, NFT transactions have skyrocketed—the market grew by 97% between 2019 and 2020, according to Marchesoni. The pandemic—and its resultant spike in online activity—has inevitably factored in. "It reflects an accelerated trend of spending more time and money on virtual goods, services, and experiences," Marchesoni says. "The NFT boom is only just beginning."

(It's also worth mentioning that NFTs, like cryptocurrencies, leave an enormous carbon footprint because the blockchain authentication process, known as Proof of Work, requires a lot of energy. According to this study, the Bitcoin network's electricity consumption rivals that of Sweden's.)

The Christie's sale is a turning point for NFTs and digital art.

In its purest form, the purpose of NFTs is to allow artists and creators to sell directly to buyers without a middleman—ie, dealers, auction houses—and, in turn, have agency over their work. Christie's foray into this market may be seen as going against the mission statement of NFTs but it's also a testament to their nascent stage and need for a more traditional broker to legitimize them for the mainstream.

"It's not as simple as minting an NFT and the collectors will come," says Diana Wierbicki, a partner and head of the global art practice at the international law firm Withers. "Having major art market participants promoting NFT sales and sharing the narratives of artists to elicit continued collector interest will be vital to the sustainability of the market–especially on the high end."

Then there is the debate over whether an intangible work—lines of code, essentially—is really art, and deserving of the hype. "It's just a different format of art, and the valuation model is no different than that used for a piece of contemporary art, the market value of which seems to be as unbelievable and arbitrary as that of any meme or GIF that has been tokenized and sold as an NFT," Marchesoni says.

If a self-destructing Banksy could fetch $1.4 million (see: Sotheby's London, 2018) and a banana duct taped to a wall can be considered a subversive statement worth $120,000 (see: Maurizio Cattelan at Art Basel Miami Beach, 2019), why can't Beeple's composite of explicit digital drawings, which depicts the likes of Donald Trump, Mike Pence, and Kim Jong-Un in grotesque, dystopian situations, also enter the canon?

"Digital art is a long established artistic medium, which has been in existence since the 1950s when civilians were first able to gain access to computing systems, but before the introduction of NFTs and blockchain technology, it was impossible to assign value to works of purely digital means," says Noah Davis, a post-war and contemporary art specialist at Christie's. "This is all to say that digital art isn’t new, it's only new to the art market—and it's making up for lost time."

Will this affect the market for traditional, tangible art?

It's safe to say that collectors of high-end NFTs don't overlap with those who bid on Monets and Picassos. The buyer behind Beeple's $69 million mosaic, for example, is an anonymous digital investor known only by his handle, Metakovan, who purchased the collage with the cryptocurrency Ether. "They are not necessarily coming from the pool of traditional buyers for the secondary sale of paintings and sculptures," Wierbicki says.

As for the investment potential of NFTs, only time will tell. "They are very new so we can't say with any certainty what the interest level in NFTs will be in five or ten years. But it will be interesting to track buyer psychology—whether they hold long-term or quickly trade," she says. "This will be a major determining factor of how collections and investments in NFTs evolve."

Call it a gimmick. Call it a scam. Call it just another get-rich-quick scheme. But exorbitant sums of money are being poured into NFTs and now that even mainstream players like Christie's and the NBA are getting involved, perhaps it would be remiss not to pay closer attention. After all, it wasn't too long ago that we dismissed Bitcoin. Early evangelists like the infamous Winkevii twins were ridiculed for their enthusiastic investment in the volatile cryptocurrency. Then they laughed all the way to the (crypto) bank.

You Might Also Like