Wu says Wichitans want a leader they can be proud of. She’s ready to ‘get back to the basics’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Watching the television news with her grandfather, Lily Wu learned English.

“The huge, heavy TV sets that nowadays are just antiques,” she recalls with a smile. “For me, it just brings me back to the innocence of childhood.”

Right away, she knew she wanted to be a reporter. As an 8-year-old immigrant, she came to think of news anchors as the “out-of-classroom teachers” who informed her about her new community.

“Back then, I feel like a lot of those stories on local TV news were really positive, or at least that’s how I remember it as a little kid,” said Wu, now 39. “It wasn’t the shooting that stuck with me.”

Accepting her first reporting job with KAKE was a dream come true. She worked her way up to a coveted anchor position, later switching to rival station KWCH.

Now, she wants to be mayor. Wu stepped away from the news business in February before announcing her candidacy.

Whipple says he’ll make another four years as mayor count. It’s ‘about serving others’

But even after winning a nine-way primary contest, she said it feels strange not to be a reporter and anchor anymore.

“What I’ve missed so much is letting people share their stories and let me help share the essence of what they’re trying to say in a minute and thirty seconds,” Wu told The Eagle.

Larry Hatteberg, who was involved in hiring Wu at KAKE 12 years ago, said she has a talent for giving voice to “the invisible people in the community.“

“There are people every day who live and work in our community, never get recognized, never get seen, and Lily, I think part of her role has been seeing these people in the community,” Hatteberg said.

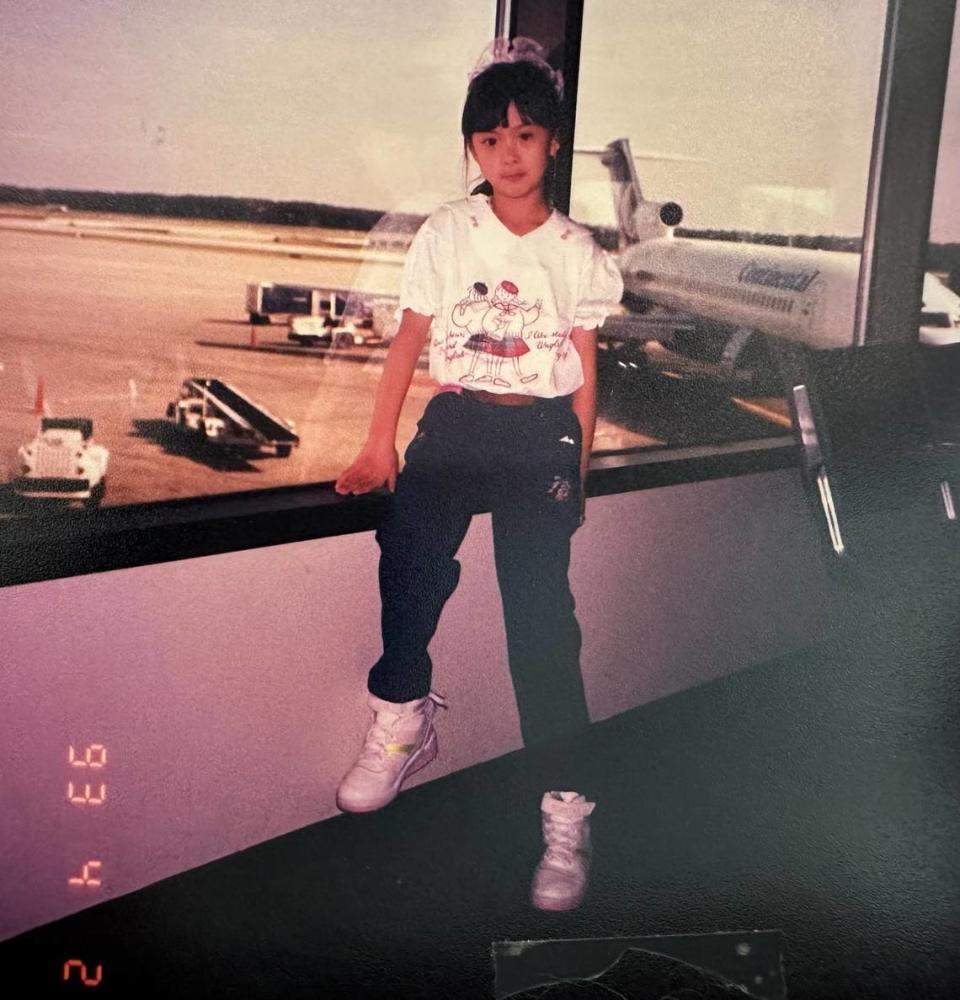

Wu’s story began in Antigua, Guatemala, where she was born in 1984, a year after her parents left China with a dream of coming to America. They moved into a multigenerational southwest Wichita home with her paternal grandfather after working their way through the U.S. immigration system.

Now, she says she wants to give back.

“For me, having served in the community as a volunteer, as a leader and in the capacity of being a storyteller, I just thought I could do more to help Wichita.”

In the stories Wu tells these days, Wichita is more dangerous than it was four years ago, and incumbent Brandon Whipple is the poster child for a toxic City Hall culture where taxpayer-funded giveaways pad private profits and the Wichita Police Department has been neglected — even as police funding has increased by $30 million since Whipple took office.

Whipple rejects her claim about sweetheart deals as posturing, asserting that if he mishandled taxpayer funds, she should have reported it.

No matter what Wu is asked on the campaign trail — from affordable renting options downtown to environmental sustainability and food insecurity — there’s a good chance she’ll tie her answer back to police. She wants to spend more to improve officer retention and bolster recruitment, “particularly from areas where officers lack respect or are undervalued,” her website says.

Whipple has accused Wu of trying to run for police chief instead of mayor. She says she wants to support Chief Joseph Sullivan, not usurp him. In general she wants to “get back to the basics of city government” — police, fire, water and infrastructure.

“I’ve been very clear from day one what the vision has been. I’ve not promised skyscrapers.”

What is Wichita mayor’s role?

Wichita’s mayor should also be its ambassador, Wu often says.

The mayor’s official duties include running City Council meetings and working alongside the council to establish policy direction, enacting laws and policies, adopting the budget and levying taxes. The mayor is paid $113,626 annually.

“I understand that I’m going to have a lot to learn, but I’ve never been afraid to take on a challenge and I’m a hard worker and I will study,” said Wu, who graduated summa cum laude from Wichita State with bachelor’s degrees in international business and integrated marketing communication, later earning her master’s in journalism from the University of Hong Kong as a Rotary Ambassadorial Scholar.

Stephanie Sorensen, the school psychologist who tested Wu for the gifted program when she was a sixth grader at Truesdell Middle School, recalls a day when Wu skipped out early on an after-school activity to help her parents with their federal income taxes.

“I do not have a memory of her being shy. I have a memory of her being respectful, respected, always reasonable and always observant, and I think she has those same qualities today,” Sorensen said.

Wu says what the mayor spends time doing outside of official duties is more important than people might think.

“You should be all over this community,” she said. “I drive east, west, north, south on a daily basis, and I think that that’s the type of — people have not seen a mayor who, I’m not married and I don’t have kids. And I’m not knocking anyone who does, but I have that extra time and I love it.”

On a recent Saturday in October, Wu’s day started with a 5K parkrun at Exploration Place. After that, she emceed her alma mater East High’s 100th anniversary parade, took in the sights and sounds of a Hispanic Heritage Month event in north Wichita and the Vietnamese Fall Festival in south Wichita, and attended the Mental Health Association of South Central Kansas’ annual gala fundraiser.

“The role of mayor, you have this microphone,” Wu said. “How can you be the best type of leader? By sharing more voices and letting those voices have a greater amplification. And so I want to amplify other people’s messages — especially those that help us increase the morale in Wichita.”

A previous president of the Wichita Asian Association, Wu directs the organization’s annual scholarship pageant at Century II. She describes Amelia Phommachanh, reigning Miss Asian Cultural Ambassador, as her “little sister.”

“I believe that God put Lily in my life for a reason,” Phommachanh says. “She really helped me understand my ethnic heritage. Something she always told me is, be grateful for where you are and where you came from, and especially for the ethnic heritage and background that you hold.”

When Wu competed in pageants, winning Miss Teen Kansas International and representing the U.S. at Miss World University and Miss Chinese World, her platform was about celebrating cultural diversity — something she still describes as her “lifelong mission.”

“Each one of us in America has some sort of ethnic heritage, and I believe that that’s beautiful to celebrate,” Wu said.

“When you understand people for the commonalities that we have, we can work on the differences. You’ve got to start somewhere where there’s commonality first.”

Politics of partisanship

Ideologically, Wu describes herself as “an independent thinker.” On paper, she switched her voter registration from Republican to Libertarian in 2022. Wu completed a yearlong D.C. Koch Associate Program through the Charles Koch Institute in her early 20s, and the billionaire’s conservative advocacy group Americans for Prosperity has spent heavily on her behalf.

But she says there’s nothing partisan about her bid to unseat Whipple, a former Democratic state representative, or the role she would play on the City Council. The politicians she says she looks up to most are former Wichita mayors Bob Knight and Carl Brewer, a Republican and centrist Democrat, respectively.

While she was campaigning at the Hispanic Heritage Month event, one man became visibly frustrated with Wu’s response to him asking whether she’s a Republican or a Democrat. Neither, she told him.

“That, to him, felt like I was dissing him, like not giving him an answer, but I was giving him an answer,” Wu said afterwards. “I’m neither of them. I’m a Wichitan. I want more people to know that this is a nonpartisan race.”

Wu shattered fundraising records in the primary, collecting more money than the rest of the city’s mayoral candidates combined.

She told The Eagle that people are paying too much attention to her contributions from well-connected Wichita business people — including many who gave the maximum $500 from multiple companies — and not enough attention to the diverse cast of more than 700 people on her donor list.

Wu said her message is the same, no matter who she’s speaking to. None of her supporters will be getting favors if she’s elected — including her partner, developer Stephen Clark II, and his family, she’s promised.

City officials confirmed to The Eagle that Clark has not bid on any city projects since 2013, when plans for Clark Investment Group to build riverfront apartments fell through. His father, Steve Clark, has said the firm does “very little in Wichita from a development standpoint.”

Wu resents the claim levied by her detractors that her own interests are out of line with those of blue-collar Wichitans.

“I didn’t grow up with wealth,” Wu said. “I still remember wearing hand-me-down clothes from people that saw an immigrant family and said, ‘Hey, they probably don’t have a lot of resources.’”

But people “should not be demonized for having resources either,” she said.

“Those with resources, come to the table not because we’re going to scratch your back but rather, ‘Hey, you live in Wichita. Invest in Wichita.’”

In some areas, she said, crime will have to be reduced before private businesses are willing to make that investment. Asked about the struggle to keep grocery stores open in northeast and south central Wichita, Wu recalled speaking to a friend from her college days about the Walmart at 13th and Oliver where she worked — one of three the company closed across the city in 2016.

“That store in particular, they had to put special sensors on meat and on just regular items that you wouldn’t expect people to steal,” Wu said.

“Is it out of desperation? Maybe their family couldn’t get food? I feel terrible, but you shouldn’t be stealing also.”

She says she supports tougher sentences for people who commit both violent crimes and property crimes, but she also wants to see the city expand its prevention programs.

Economic development in Wichita

As of now, Wu doesn’t have a vision for developing the downtown riverfront or anywhere else for that matter. That’s the point, she says.

“When people keep asking me, ‘What do you want with the riverfront?’ I’m not telling you what I want because I believe that the community needs to say what they want,” she said.

Previous community engagement efforts have fallen short, Wu said, and it will take another round of outreach and a sound plan before anything transformational happens on the east bank.

COVID-19 put Wichita’s riverfront plans on ice, but the Riverfront Legacy Master Plan was already in peril following a groundswell of backlash from residents opposed to the idea of tearing down Century II.

Wichita’s 10-year capital improvement plan calls for preserving Century II but also includes $400 million for an “expanded and enhanced convention facility.” It does not identify a funding source.

Wu said new convention center space is not a priority for her, and she doesn’t think it’s the kind of project that should be supported by a city- or county-wide sales tax increase, as consultants recommended for the roughly $1 billion Riverfront Legacy Master Plan.

“I don’t think it should be on the backs of my mom and my dad,” Wu said. In general, she doesn’t think it’s the city’s responsibility to drive economic development.

“That is the role of industry.”

But she said City Hall has been routinely taken advantage of by developers who game the system to boost their profits at the expense of taxpayers.

“We shouldn’t be giving out handouts if the return on investment does not make sense for the community,” Wu said.

“When you have big names like Topgolf, they don’t need incentives to come to Wichita. If we’re a really great market, they’ve done market research.”

Whipple and three Republican City Council colleagues comprised the one-vote majority that green-lit a $10 million subsidy for development at the K-96 & Greenwich STAR bond district in 2021, including up to $3 million in future sales tax revenue for the multi-billion-dollar golf entertainment company through the state incentive program.

Wu says she wouldn’t have voted for the Topgolf subsidy if she were in office. Whipple has repeatedly asserted that she doesn’t know enough about STAR bonds to ensure city projects intended to pay for themselves through future sales tax revenue don’t fail. Both city STAR bond projects, in downtown and northeast Wichita, were set into motion before Whipple was elected.

Wu also points to $725,000 in tax increment financing (TIF) for the River Trail Village, a new 40-home community in Riverside that received city incentives, as an example of the City Council’s poor stewardship of taxpayer dollars. Whipple voted for that deal, too.

“The Riverside homes, that’s not blighted either. That’s right by a golf course,” Wu said.

“We need to have clear definitions of what is blight and what is not.”

She’s proposing an advisory council to vet the city’s economic development ventures and ensure developers who accept incentives without delivering on promised results are held accountable.

Looking to Wichita’s future

Wu recently attended an open house for the Wichita Indochinese Center-Butler Community College English As A Second Language program. She said great strides have been made in providing opportunities for economic uplift for non-native English speakers since her own family immigrated in 1993.

“Whether you’re a full English speaker or a limited English speaker or a non-English speaker, we want people to be part of the community and contribute and find value in work,” Wu said.

She’s immensely proud of her parents, both of whom are still working — her mother as a hairstylist and her father as a chef in the Dillons Chinese kitchen. She still lives with them, she says, in part because it’s always been her role to help them navigate the world.

Not that her parents aren’t capable. She remembers the admiration she felt for her mother as she boarded the bus to Guatemala City to bring back food, clothes and other goods for the family’s variety store in Antigua after leaving her own parents and family behind in China. In Wichita, she remembers her father digging their basement by hand.

“I think that he would have been an amazing architect or someone in engineering, but he didn’t speak English,” Wu said. “So I wish now, moving forward, anyone in a situation like that, I want to expose them to these opportunities.”

One of the reporting projects Wu is most proud of is her “Building You” series, a collaboration with local workforce development centers to connect job-seekers with opportunities in south central Kansas.

Wu’s website outlines a plan for an economic advisory board with representation for the city’s top 50 employers, and she has the endorsement of the Wichita Regional Chamber PAC.

“I was thinking specifically, we could divvy up the list of our 50 largest employers between the seven people on the council and try to make sure that we are still listening to workforce needs in our community and helping share that news with our community,” Wu said.

“But it has morphed into more of like a mayor’s advisory council where I would like to have top leaders in education and top leaders in industry help advise — what are things that help move Wichita forward?”

Wu said part of her economic plan is “to boomerang people back” to Wichita who grew up here. She’s thinking specifically of her only sibling, little brother Carlos, who now lives with his wife in Milwaukee.

She said she’s driven by a deep sense of gratitude for the city that opened up a world of opportunities to her 30 years ago. She hopes she’s the one who gets to lead Wichita into the future.

“This community really has given me all of this. I just feel like I can be a force for good.”