WWI veterans denied Medal of Honor because of race may be reconsidered, 100 years later

Tewanna Anderson Edwards always admired her great uncle’s smile. It wasn’t until after he died that she learned about all the battles it hid.

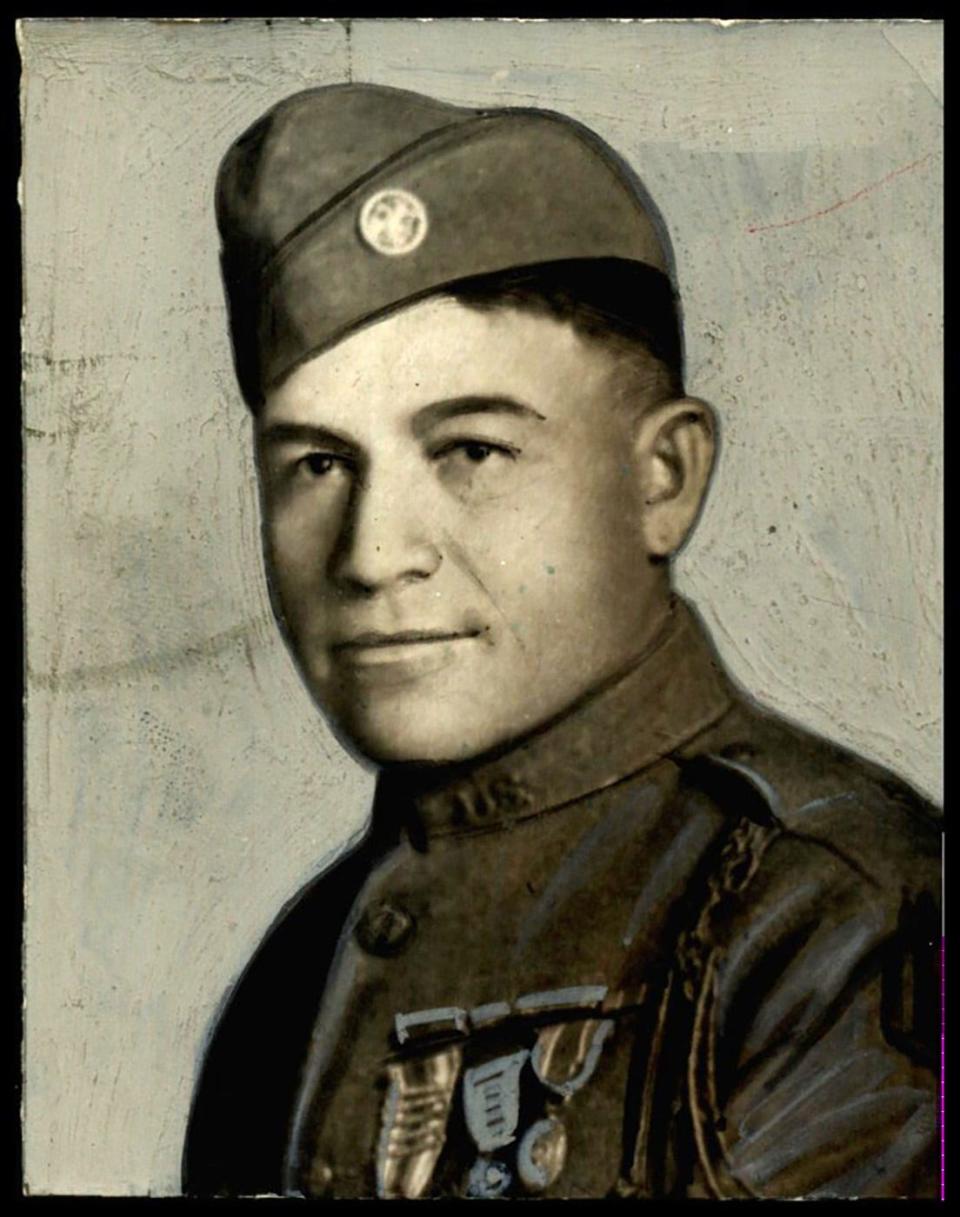

Otis Leader was among the first wave of American soldiers to arrive in France when the U.S. joined World War I in 1917. He fought in several battles where he was wounded or gassed. He never fully recovered, but he returned to the battlefield. Historical accounts credit him with capturing German soldiers and two machine guns in July 1918.

He was lauded as a hero in Europe and upon his return to southern Oklahoma. Yet the U.S. military never bestowed its highest honor on Leader, who was Choctaw and Chickasaw.

“They did so much for our country, but they never really got any recognition for what all they did,” said Anderson Edwards, speaking about Leader and other Choctaw men who served in World War I. “We just need to identify more with our unsung heroes.”

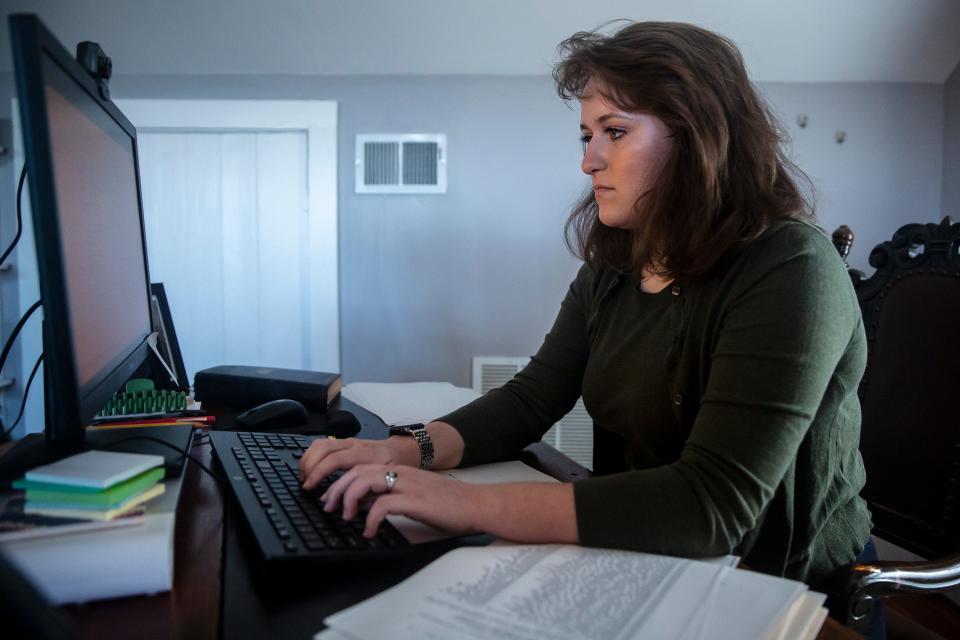

A team of researchers is reviewing the actions of Leader and hundreds of other World War I veterans who may have been denied the Medal of Honor because of their race or religion. No one knows how many may have been overlooked, so the researchers compiled their own list by poring through federal records, historical documents and newspaper accounts.

More: Seniors, adults with disabilities create Memorial Day arrangements for veterans' graves

They have so far found 214 men — including Leader and 22 other Native Americans — who received distinguished honors but never the U.S. military’s highest award. Nine of the Native veterans are from Oklahoma. Two lived in towns that bordered the state. The others are from Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, Washington and Wisconsin.

The researchers' findings will go to senior military officials to make the final decision on Medals of Honor more than 100 years past due.

Stories of service so long ago can seem distant. But Memorial Day offers a reminder about what each veteran endured during the war and after they returned home, if they did at all, said Ashlyn Weber, who is helping lead the review as associate director of the George S. Robb Centre for the Study of the Great War at Park University in Missouri.

What makes them all amazing is that in the face of danger, they did not turn away, “They threw themselves in front of it and did the best that they could do,” she said.

Why did so many Native Americans enlist in World War I?

The sweeping World War I review is bringing back to light a conflict often overshadowed and misunderstood, particularly surrounding the experiences of Native Americans.

An estimated 12,000 Native Americans served at a time when U.S. domestic policy still was aimed at breaking up tribal nations. Native Americans weren’t granted U.S. citizenship unless they agreed to divide tribal land into allotments, which for the most part had happened in Oklahoma.

“My sense is that Cherokee citizens and other Native Americans were fighting for a cause and an idea, even if that idea fell short when it came to the administration of federal Indian policy,” Cherokee Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. said.

More: Why do we observe Memorial Day? Here's the true history of the holiday

Like many tribal nations, the Cherokee Nation holds military service in high regard. Native boys and young men were also conditioned to go into the service through their experiences at boarding schools, which operated in the 1800s and 1900s and enforced strict rules, uniforms, group marches and bed inspections, said William Meadows, a Missouri State University professor and author of “The First Code Talkers: Native American Communicators in World War I.”

Newspaper accounts of Native Americans in the war emphasized stereotypes that played out on the battlefield. Superiors often assigned scouting and reconnaissance to Native men, because they were believed to have innate military skills, such as the ability to move more quietly and see better at night, Meadows said. Some also volunteered for those roles.

The dangerous scouting duties contributed to higher death and injury rates among Native Americans compared to their comrades. Of the 23 Native Americans who are part of the Medal of Honor review, five died in combat. Those who survived often returned with lingering health issues and found a lack of formal support systems for veterans living in tribal communities.

A first of its kind review into World War I

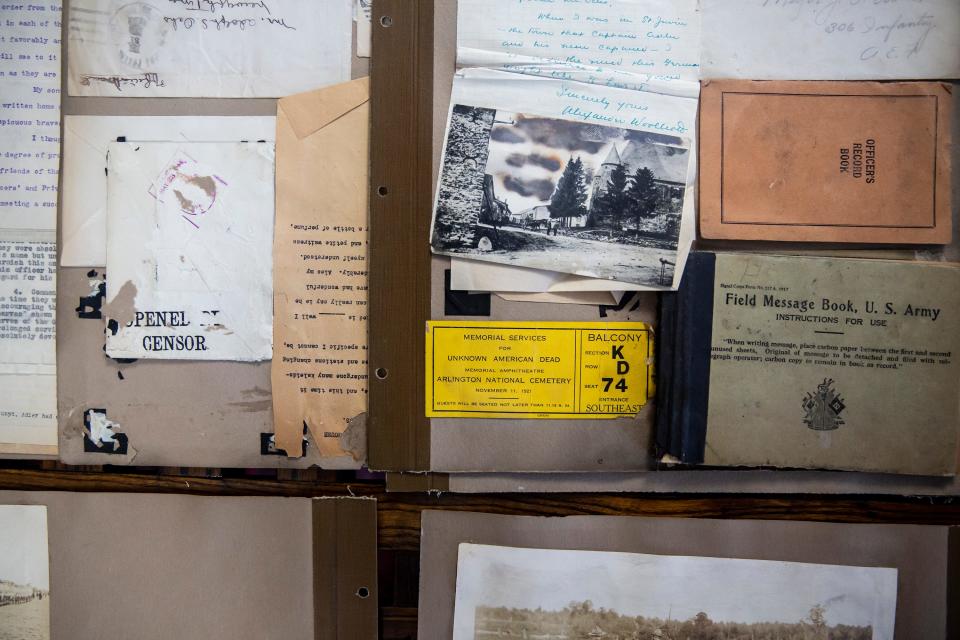

Otis Leader recounted the battles he witnessed in journals but talked little about his own heroics, said Sarah Elisabeth Sawyer, a Choctaw author who is writing a biography about Leader. He marked the war’s end on Nov. 11, 1918, from a hospital bed, where he was recovering from wounds suffered in action.

He was awarded a Silver Star Medal, a Purple Heart and a Croix de Guerre with bronze palm, a top French honor.

A century later, the wide-scale review into the deeds of Leader and others started to take shape. The Valor Medals Review Project is the first organized effort to consider the role of bias in the honors awarded to Native American, African American, Asian American, Hispanic American and Jewish American service members.

Military awards have strict evidentiary requirements, and filling out paperwork wasn’t always a top priority in the field, Meadows said. Some acts of valor are lost to history because the right forms were never filled out.

Timothy Westcott, who is leading the review, said the effort began after the discovery of a Medal of Honor nomination for William Butler and George Robb. Butler was an African American sergeant, and Robb was a white officer who oversaw African American troops in a segregated unit. Only Robb received the award.

In his journals, Leader did not write about facing discrimination in the trenches, Anderson Edwards said. But it influenced his daily life, down to his decision to enlist after he was accused of being a foreign spy. “Because he was dark and looked different than the majority of people,” she said.

The review led by Westcott and his team is specifically taking a look at the service of veterans of color and Jewish service members who were awarded a Distinguished Service Cross or its Navy equivalent, were recommended but denied for a Medal of Honor, or were granted a Croix de Guerre with palm. It is modeled after similar but less expansive World War II reviews.

The review team also worked with lawmakers to introduce two bills in Congress that would give military officials a set timeframe to act on the Medal of Honor recommendations.

'Unsung heroes' and their actions in World War I

Stories of heroic deeds and the veterans behind them have emerged as part of their research.

Army Sgt. Alfred Bailey, who was Cherokee, was fighting alongside other soldiers in July 1918, when amid smoke and chaos, he killed two German machine-gunners and captured a third.

He was wounded six days later and died from his wounds. He is buried in Hulbert, the same town where he was born. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Army Private Calvin Atchavit was shot in the arm during a battle in September 1918, but he kept fighting and killed one German soldier and captured another. He was one of eight Comanche veterans wounded in action during World War I, and one of 62 who served, said Lanny Asepermy, who retired earlier this year as the longtime historian of the Comanche Indian Veterans Association.

More: Oklahoma Memorial Day weekend events range from military tributes to family fun

Atchavit accepted his Distinguished Service Cross at the 1919 Oklahoma State Fair, according to an article published in his hometown newspaper of Walters. He died in 1943 at the age of 50.

Joseph Oklahombi, one of Oklahoma’s most prominent World War I veterans, is not part of the review because his military honors don’t meet the criteria. His unit was recommended for the Distinguished Service Cross, but it was never awarded.

“This man did something that most people could never accomplished in a short period of time,” said Judy Allen, a longtime Choctaw Nation historian. She and other tribal leaders have been lobbying since the 1980s for him to be upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

Meadows, the Missouri State researcher, also has written in support of the effort. He said Oklahombi’s unit was overextended when Oklahombi went ahead of his comrades and spotted two Germans manning a machine gun unit. He killed the pair and took over the machine gun. His unit was able to capture dozens of Germans and hold their position for days.

Oklahombi was among the Choctaw men who served as code talkers. Their work is credited for having a major impact in the final weeks of the war, but it was not singled out for special recognition until decades later.

Anderson Edward said she hopes more attention and research will ensure their heroic actions are recognized and passed on to the next generation.

“They’re just the unsung heroes, you know?”

Molly Young covers Indigenous affairs for the USA Today Network's Sunbelt Region. Reach her at mollyyoung@gannett.com or 405-347-3534.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: Were Native American WWI veterans overlooked for Medal of Honor?