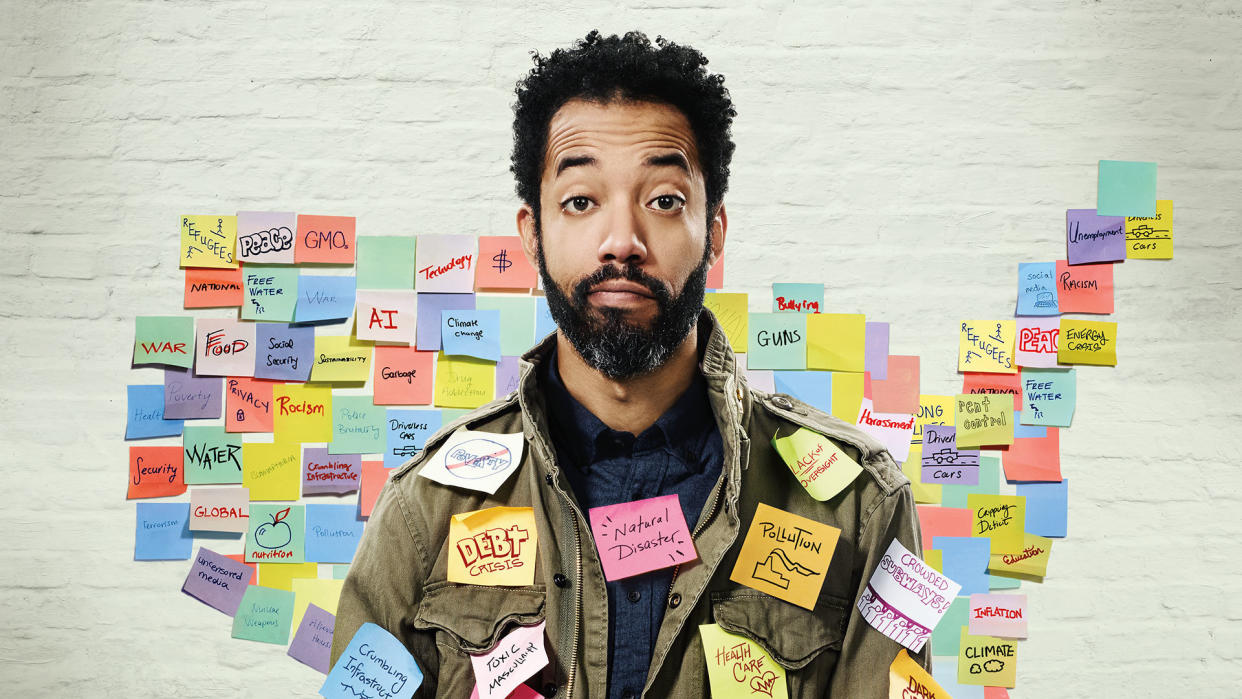

Wyatt Cenac Talks Tribalism And Lessons Learned From Season 1 Of 'Problem Areas'

When Wyatt Cenac’s “Problem Areas” debuted on HBO earlier this year, the comedian set out to craft a show that embodied his own tone ― funny and without fret. The show spent its first season defying the norms of late-night comedy shows, electing to not only bypass the traditional live audience format but also spend the entirety of its time parsing the intricacies of a single subject: policing in America.

Season One of “Problem Areas” examined socioeconomic issues in areas across the country with a particular focus on police departments, assessing the structural difficulties they face as well as their struggles garnering community trust amid a raft of national stories involving police misconduct. HBO announced in May that the show would be renewed for a second season.

HuffPost sat with Cenac at CultureCon, an annual event for creatives of color, to discuss how he developed his signature dry wit and what he’s learned about people of all stripes through his HBO show.

Where did you develop your comedic voice? Your delivery and your intonation are very unique to you. Is that framed by any specific parts of your upbringing?

Some of it is probably just me. If I was a dentist, I’d probably still talk the same way, and I’d deliver information about your cavities in the same type of way. When I was coming up, my comedic influences wound up being a mix of a lot of things. On one hand, there were definitely things that are considered traditional comedy inspirations, like “Saturday Night Live” or “Monty Python.” But those were also spaces where I didn’t necessarily see myself outside of a few people, so I also found a need to reach beyond that.

What did reaching beyond that entail?

I was fortunate that by the time I was in high school, “In Living Color” was on the air, but outside of that I remember watching “Late Night at the Apollo,” and after that there was a show called “Uptown Comedy Club” that Tracy Morgan, Flex Alexander and others were a part of. It was a sketch show kind of like “SNL,” but it was done in Harlem. I was looking for things like that. So for me, it was wanting to understand what the popular idea of comedy was, but also wanting to, then, look and see comedy that looked like me. So maybe in some way, my voice came out of trying to appreciate and respect both of those things.

“Problem Areas” focuses heavily on policing, and I’m wondering if you’ve noticed — in the age of President Donald Trump and his abnormally pro-police Department of Justice — viewers’ palates have changed a bit. Did you sense a greater interest in “Problem Areas” and the things you’re uncovering because of the time in which we live?

We’ve been fortunate that the audience that’s found us seems to enjoy the stories we’ve told and the issues we’ve tried to address. They seem to be engaged with the idea that there are people working to address these issues in ways that could be replicable in their own cities.

Can you give me an example?

Whether it’s people doing work on the ground who are able to push for policing legislation, which we discussed in the first season. Or whether it’s highlighting departments that not only put officers on the street, but devise ways to have officers work with social workers and mental health experts. Once you see that and you see it’s possible — one, you don’t feel as desperate. And two, one of the things I found interesting about Season One was that people who were doing the work in these communities were reaching out to the show through social media, so we had restorative justice advocates telling us they were doing this work in Brooklyn, in Detroit, in Los Angeles and all over. That was the coolest thing to me: seeing that other people are doing it, and maybe if enough of those voices find one another and bubble up, it’ll drown out the more bigoted, angry voices that have found each other and gotten loud.

Have you noticed a difference in the way you’ve been received by police departments around the country since Season One? The show has now been around for a while and you’re not exactly hard to spot in a crowd.

[Laughs] I don’t know. I mean, my day-to-day interaction with police is just the minimal observations I make when I see them on the subway platform. I think when we did the show at first, the fear was, like, “OK, is my subway commute gonna get fucked up? Will I get stopped more? Will they check my bags just to hassle me?” But I feel like, anecdotally, from a lot of people who work on the show, some of them have family members who may have connections to law enforcement. Even in talking with the guy who works for security in our building, once we started airing episodes he was stopping people on our team saying, “I wanna talk to Wyatt.” [Laughs] He was like, “I was watching your show, and you’re harsh but fair.”

I understand. It seems like when you get down to a personal level and speak to people outside of their tribes, you get a far more authentic ― maybe even conciliatory ― response.

I totally agree with that. I think that’s part of the ethos of the show. Yeah, the national conversation is one that becomes incredibly tribal and polarized, but if you wind up talking to people on a one-to-one level, what becomes fascinating is how they then — outside of that security blanket — there is a rationality and reason you can often speak to. The problem is that if they go back to their tribe, they unlearn all of that.

Right. Instilling a long-lasting empathy in others is difficult, exhausting work.

I don’t know if you’ve watched Sarah Silverman’s show, “I Love You, America,” but in the first season she interviewed a guy who used to be a white supremacist and he talks about how people pulling him out of his world and talking to him as an individual revealed that his previous way of thinking was hateful and coming from a place of anger and fear. And the anger and fear he was feeling were creating an exponential fear and anger among the disenfranchised people in his community.

Is engaging people like that a model you think should be replicated?

I don’t know if that’s the work I want to do. [Laughs] I don’t know if I wanna go around trying to buy ice cream for every bigot out there, but I do think there’s something to the idea that you need to get smaller and start looking at specific communities. The community of Ferguson, [Missouri,] for example — it takes the whole community to try to fix and atone for a history of racism and discrimination that hasn’t just played itself out in policing but also in resource allocation and education and employment.

I feel you on that.

It requires the entire community recognizing a need to fix that. It gets more personal on the community level. It’s like, “Oh, you’re my city councilman and you live right there. You need to understand my struggle and I need to understand yours.” In that area, they’re going to fix that more on the ground with those people than they can with me ― a person on television living thousands of miles away.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

More from HuffPost Personal...

Alfre Woodard On Going Rogue In Her 'Luke Cage' Love Scenes

David Alan Grier On Discovering 'New Negroes' At Yale And The 'Black Rage' In His Blood

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.