Yakamas to have 1st ceremonial elk hunt on Rattlesnake Mtn. in Eastern WA in 80 years

The Yakama Nation will hold its first ceremonial elk hunt since World War II on the Rattlesnake Mountain area of the Hanford Reach National Monument in Eastern Washington.

No date has been made public, but the hunt is planned before the end of the year.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which manages the national monument, said the Yakamas notified it, the Department of Energy and the Washington state Department of Fish and Wildlife of its plans.

The Treaty of 1855 gives the Yakamas permission to hunt, among other activities important to their culture, on the monument, including the area closed to the public that includes Rattlesnake Mountain.

“We are re-establishing something very sacred to our people,” said Phil Rigdon, superintendent of the Yakama Nation’s Natural Resources Department.

Gathering and hunting to provide food for their community is important to who the Yakamas are as a people, he said.

A limited number of Yakamas will participate in the initial elk hunt and then the Yakamas will be working toward arranging future hunts, Rigdon said.

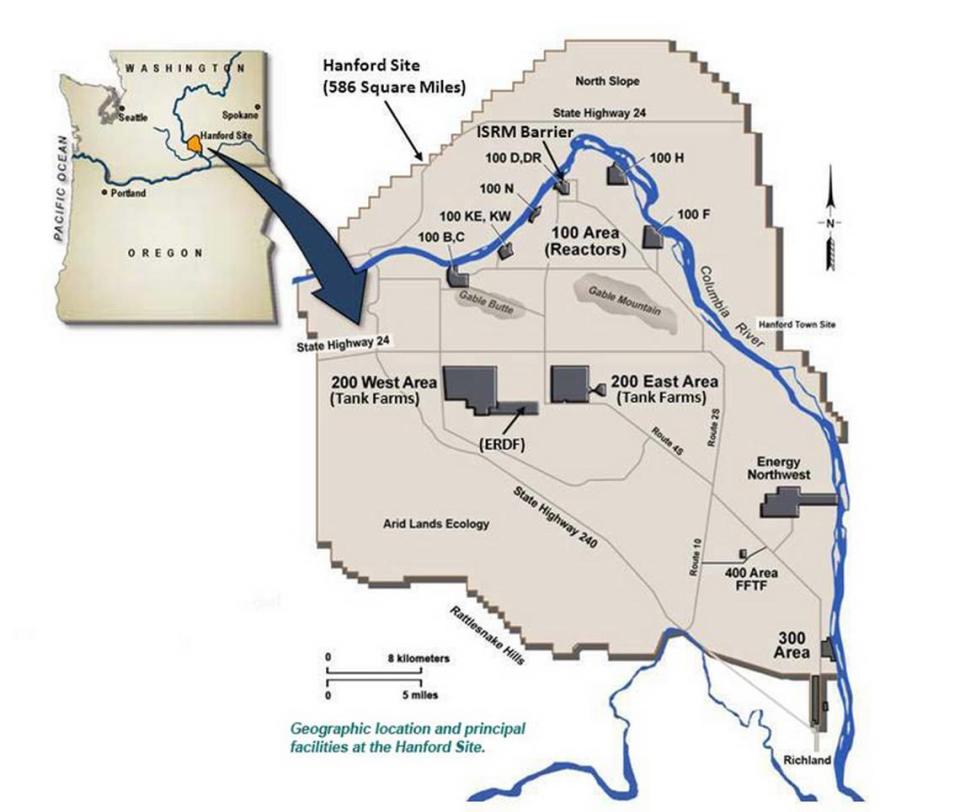

About 1,600 elk roam DOE Hanford land, including the Arid Lands Ecology Reserve of the monument, according to U.S. Fish and Wildlife estimates.

The reserve south of Highway 24 and west of Highway 240 includes Rattlesnake Mountain. The elk also cross Highway 240 and are seen roaming the former production portion of the nuclear reservation down to the Columbia River.

The herd is too large for the area, and Fish and Wildlife, DOE and the state have discussed ways to manage it for years.

Elk are believed to have migrated to the Rattlesnake Mountain area from the west in the 1970s, and from 1984 to 2000 the population grew from from about 50 to more than 800 and has continued to grow since.

There are few natural predators in the area.

Elk hunting is allowed north of the Columbia River on the Saddle Mountain, Ringold and the east Wahluke Unit of the Hanford Reach National Monument, in areas open to the public.

Past elk hunt proposals

At least twice in the last 20 years U.S. Fish and Wildlife has proposed plans to allow controlled hunting of herd on the closed Arid Lands Ecology Reserve, but neither plan moved forward with a hunt.

The reserve is closed to the public to preserve cultural and ecological resources and for the security of the Hanford nuclear site, according to federal officials.

The latest draft plan said the Yakamas were not then allowed to hunt on the reserve, but the Yakamas maintain they need no permission from the federal government.

Settlers and tribes, including the Yakama Nation, were forced to leave the area of the monument that includes Rattlesnake Mountain when the federal government seized the land as part of the Hanford site nuclear reservation in 1943.

Rattlesnake Mountain, which became part of the Hanford Reach National Monument when it was established in 2000, was used as part of a security perimeter around the production portion of the Hanford site as it produced plutonium for the nation’s nuclear weapons program from World War II through the Cold War.

There has been little human disturbance for eight decades on the mountain, which has the highest elevation in Benton and Franklin counties, with a windy, treeless peak of 3,575 feet.

Some research, mostly related to natural resources, has been conducted on the reserve, and there is a communication tower system that was built to provide service for 18 Mid-Columbia agencies, many of them using the facility for emergency communication.

The Department of Energy owns the land and it has been managed since about 2000 as part of the national monument by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife works with tribes that have traditionally used the area to provide access for their ceremonial needs and traditional use at culturally significant sites, said Megan Nagel, spokesperson for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

In 2015 a jury found a member of the Yakama Nation guilty of driving off road on the Arid Lands Ecology Reserve after he was stopped by federal and state officers driving a pickup with three passengers in the cab and elk carcasses in the pickup bed on the reserve in 2011.

But U.S. Judge Stanley Bastian took no stand on whether the defendant had treaty rights to hunt elk on the reserve, after the prosecution and defense argued about whether the defendant had the right to enter the reserve and hunt there.

In 2005 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife considered allowing tribal and elk hunting on closed portions of the Hanford Reach National Monument to manage the growing elk herd, but DOE opposed the plan.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife in 2011 again considered allowing elk hunting on the land near Rattlesnake Mountain that is closed to the public, but no controlled hunt was planned.

The summit and slopes of Rattlesnake Mountain were to be excluded under the 2011 draft plan, but other rugged canyon areas of the Rattlesnake Hills to the northwest of the mountain would be opened to hunters. Trophy bulls were excluded from being shot.

The state of Washington and the Yakama Nation had asked for help in 2011 to gradually reduce the size of the herd from an estimated 700 elk then to about 350 to reduce damage to nearby private land and damage to the national monument, according to the draft hunting plan.

Change in Rattlesnake Mountain stewardship

In December the federal government announced it was proposing entering an agreement with Eastern Washington tribes to give them co-stewardship authority for the use and protection of Rattlesnake Mountain, according to a new memorandum of understanding.

A document setting that goal and agreeing to other steps was recently signed by the Department of Energy and Department of Interior, according to a DOE announcement early this month.

“We heard tribal perspectives and we agree on the importance of continued collaboration to incorporate tribal knowledge and expertise in future stewardship of this important area of the Hanford Site,” said Ike White, the senior adviser for the DOE Office of Environmental Management.

Rep. Dan Newhouse, R-Wash., responding to the announcement, pointed out that federal law requires the two federal departments signing the agreement to expand public access to the top of the mountain, the most prominent natural landmark in the Tri-Cities region.

“This new shared commitment by both agencies and the tribes must consider the legal requirement for responsible public access while further preserving the sacred site,” he said Wednesday.

Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., called the federal government’s announcement an important step in the right direction.

Acknowledging and empowering Columbia Basin tribes as partners in co-stewardship of the site sacred to them is long overdue, she said.

“The federal government must collaborate closely with Tribes on co-management plans, educate the public on its full history and incorporate Tribal knowledge in its stewardship,” she said.