For years, doctors told me nothing was wrong. Now I know hip dysplasia was causing my pain

After nearly two decades of undiagnosed pain, it was a trip to the National Comedy Museum in Jamestown, New York, that finally pushed me over the edge.

Between every Bob Saget joke or history of comedy lesson I read on the wall, I had to sit down. Fun fact: Many of the chairs there make fart noises when you sit.

An hour into the tour, I was in excruciating pain in my low back.

It was a familiar pain, one I’d had most days since I was about 15. Most of the time it was a dull ache, mild enough to fade into the background, but if I stood too long or walked too far, it was agonizing. I usually blamed it on whatever sport I was playing at the time.

But in my early 30s, I was waking up to the fact that I was in a level of pain that was not normal for my age.

Doctors had told me nothing was wrong, but I was in pain. That pain was real.

It was self-advocacy, and the expertise of a physical therapist, that finally led me to a diagnosis: Bilateral hip dysplasia.

June was Hip Dysplasia Awareness Month, but until two years ago, I had little awareness of hip dysplasia. It’s commonly discussed in babies and with certain breeds of dogs. The number of times I’ve been compared to a golden retriever in the last two years is high.

Because my case of dysplasia went undiagnosed for so long, and because it is so rarely diagnosed at all, I am now committed to raising awareness of this condition and the fact that there is something that can be done about it.

Hip dysplasia can be in one or both hips. “Bilateral” means I have it in both hips, although my left was worse than the right. You can be born with it or develop it as you grow into your adult body.

Dysplasia means the head of the femur, the top leg bone that feeds into the hip joint, doesn’t have enough coverage from the hip socket. As a result, it doesn’t sit in the hip socket securely. The femur doesn’t have enough support, and the muscles around the joint are left to compensate.

My pain was mostly in my sacral area of my low back, but as is common with dysplasia, I later developed pain in my groin because my labrum, the cartilage in the joint, was torn.

It was my physical therapist, Tim Shanor at NovaCare Rehabilitation in Stow, who said, “I think your problem is in your hips.” I was stunned, as this had never occurred to me. It had apparently also never occurred to my pediatrician — although I don’t remember how much or how significantly I brought it up to her — or the neurologist I saw three years ago when I severely strained my low back, or the physical therapist I saw in my 20s who insisted my core just needed to be stronger.

An answer to years of pain

Tim sent me to University Hospitals for a consultation with Dr. Michael Salata, who is the Cleveland Browns orthopedist. Salata confirmed I had an impingement in my hip, which is caused by extra growth on the side of the femur from it rolling around in the socket, and a torn labrum on my left hip.

He also said I had underlying dysplasia, and sent me to his colleague, Dr. Robert Wetzel, a hip preservation specialist, who confirmed the dysplasia diagnosis and explained I would benefit from a procedure known as a Periacetabular Osteotomy (PAO).

If I didn’t have surgery, I was at risk of developing arthritis and needing an early hip replacement. I would also continue to have the same pain I’d lived with since I was 15. It was a scary choice, but I was thrilled to hear something could be done. I wish I had known sooner.

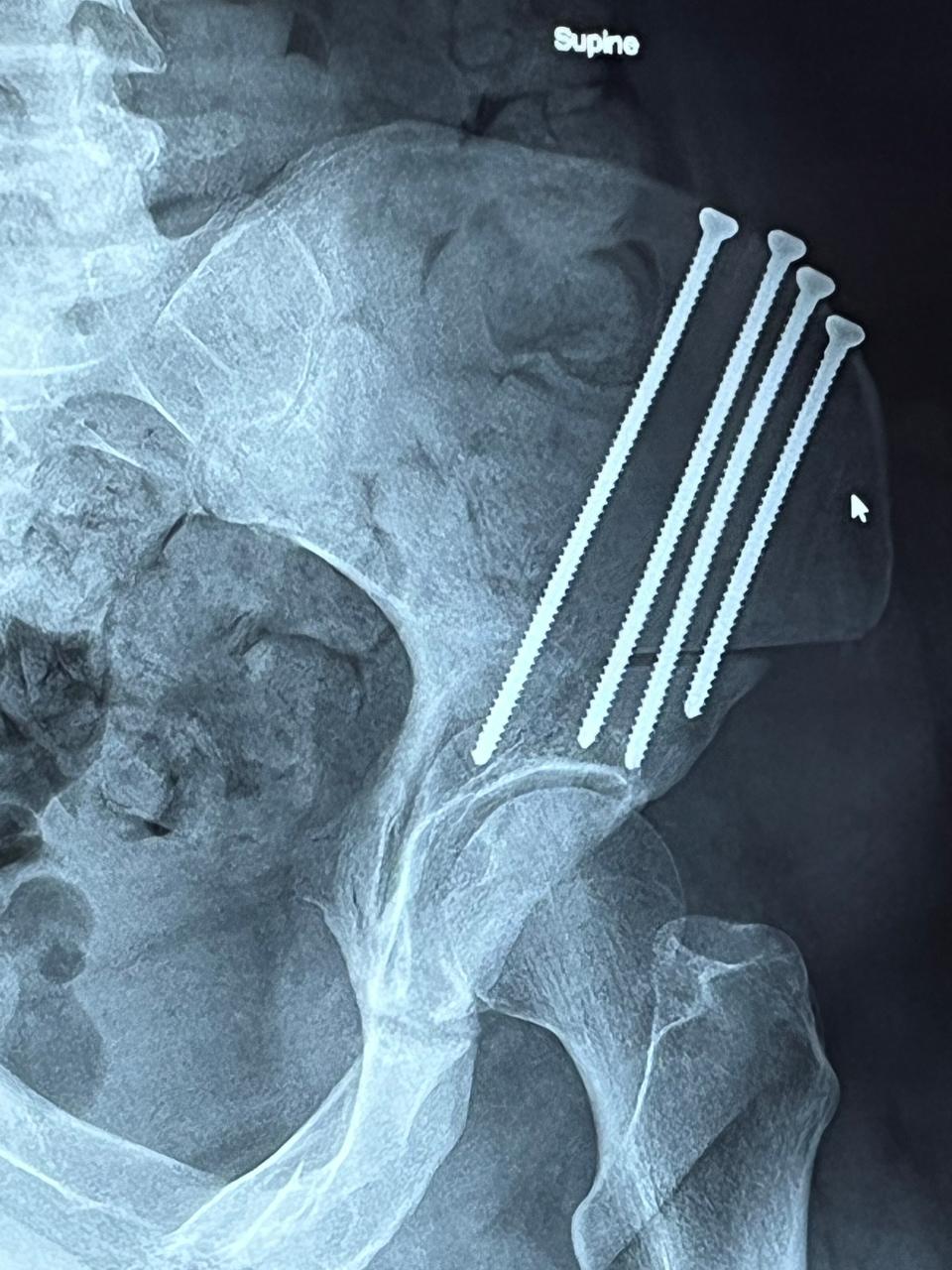

In a PAO, they cut out a section of the pelvis, rotate it to give more coverage to the head of the femur, and use screws to set it in place. Bone then grows around the gaps, and eventually, they remove the screws. Picture a hip socket like a person holding an umbrella at an angle. The surgery uprights the umbrella so it is directly over the person. An arthroscopic procedure to fix the damaged cartilage and shave down extra bone growth often accompanies the PAO.

About a year after my diagnosis, my surgery was scheduled for a Monday last October. Everything went well, and I went home that Friday. The anesthesiologist who checked on me daily asked me if I wanted to stay another day—a rarity in the health care world today. He told me this is the hardest elective surgery they do. They broke my pelvis and rebuilt it. There was no rushing this.

I recovered at my parents’ house, grateful for them and every visitor, especially those who brought ice cream, for about eight weeks before I was able to stay on my own. I started physical therapy at six weeks. The protocol calls for complete bed rest for six weeks with minimal physical activity. At three weeks, I was allowed to start a small exercise of tightening my quad muscle and releasing it.

I was driving at about seven weeks, and back to work around 12 weeks post-op, mostly working from home for the first few weeks.

Don't miss out: 6 reasons why you should subscribe to the Akron Beacon Journal

I have had a few setbacks, including a fall off my crutches at five weeks that caused soreness but thankfully no real damage, and tendonitis that developed on the outside of the hip, requiring another procedure this spring and another four weeks of doing very little.

I’m now eight months post-op and finally feel like I’m moving forward again. I can walk about a mile before I need to rest, but I can feel my leg and my hip getting stronger now. I have had multiple days where I walked 10,000 steps or more. I was warned the recovery would take nine to 12 months but could take as many as 16 months. At only eight months along, I have to remind myself it’s OK not to be healed yet.

I also still may have one more hip to go. The right side is not nearly as bad as the left was, so it’s going to be a judgment call between me and my surgical team. I need to be completely healed from the left side first, so I don’t have to make a decision yet. But I’m so grateful that it’s a decision I get to make because I have accurate information.

I am now a big advocate for self-advocacy, and for taking one’s own aches and ailments seriously.

There might just be something you can do about it.

Contact reporter Jennifer Pignolet at jpignolet@thebeaconjournal.com, at 330-996-3216 or on Twitter @JenPignolet.

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Nearly two decades of back pain ends with surprising diagnosis