On New Year's Eve 1862, Black Americans awaited Emancipation. It began a new tradition

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

New Year’s Eve is Watch Night. It is Freedom’s Eve.

For 160 years, the passage to each new year has marked the anniversary of one of the greatest turning points in American history: the proclamation, however imperfect, that led to the end of slavery in the United States.

On Sept. 22, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln declared that he would free enslaved people in Southern states if those states did not end their rebellion.

He signed his threat into a decree on New Year’s Day.

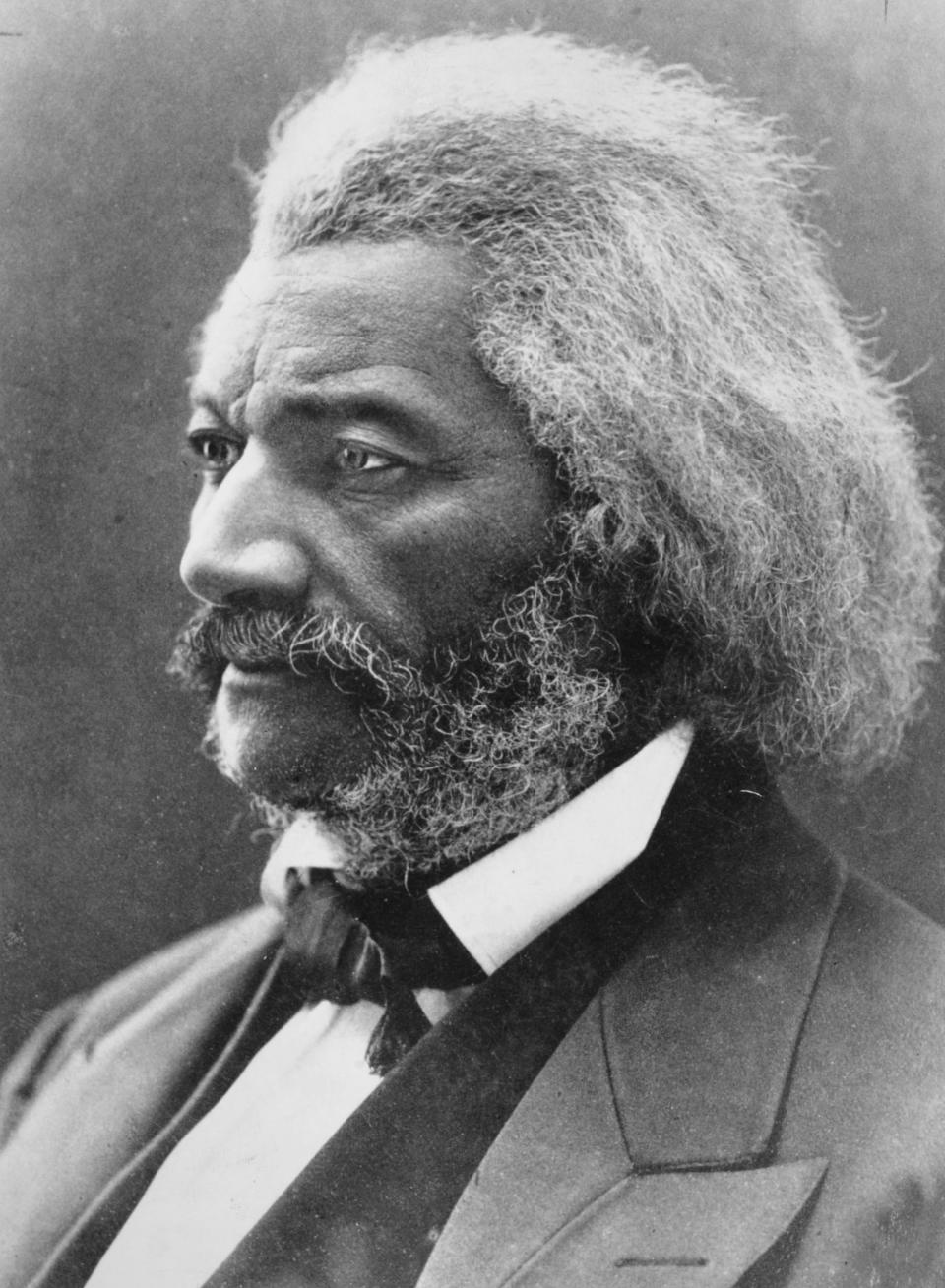

Northern abolitionists, including Rochester’s Frederick Douglass, held vigil to wait for a signing they feared would not come. In Southern states, many historians believe, enslaved people held reverent watch in secret midnight services on the eve of the New Year, waiting for liberation that was just a rumor.

These Watch Night services continue today, counting down the minutes to midnight and freedom. And Rochester has a special place in that history.

Rochester’s Greater Bethlehem Temple is on the site of Douglass’s old AME Zion church at 40 Favor St., the same place where he first published The North Star to advocate for the end of enslavement in America. The church also was a stop on the Underground Railroad to freedom.

And it is where, on the Sunday before New Year’s Eve in 1862, Douglass called from the pulpit for vigilance to ensure the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Greater Bethlehem pastor Beverly Renford still honors that history, as did her father before her, in a service that can stretch from 9 p.m. until after midnight.

“What we usually do is have the reading of the meaning of the Watch Meeting and go all the way back into the history so that our young children, our young people, and maybe some parents who don't know that people died for us to be able to do that — we use the reading to keep it fresh in the minds of the people. Emancipation is the root of a lot of this.”

This year, Greater Bethlehem will hold their Watch Night in adversity. Four days before Christmas, a 35,000 gallon-a-minute water main break from failed city pipes sent a flood rushing toward the landmark church.

Previous coverage:Boil-water advisory that affected large portions of Rochester lifted

The fast-rising waters tore through the lower-floor offices and dining room and ripped Renford’s ministerial certificates from the walls — disabling the church’s boiler, knocking down refrigerators and racking up tens or maybe even hundreds of thousands of dollars in damage the church has yet to calculate fully.

Pending much work and money, the church will be closed for services.

But the Watch Night meeting will still take place, streamed live from Renford’s home to viewers as far away as India, she said.

“This church started in my parents’ home. And we're again conducting service in my home,” she said. Those services happened before her father took over the abandoned century-old landmark in 1979, fixing it up to meet city code and bringing it back to service as a church.

The Watch Night tradition will continue even in this year, said Renford’s daughter Nicole, because it must, as a link back to the day of Emancipation. Nicole Renford remembers watch meetings going back to her childhood at Greater Bethlehem.

“It's something that is a tradition that we ought to continue and keep alive, because it is very powerful,” she said.

Emancipation was promised in America but not guaranteed

But from the pulpit in Rochester in 1862, the same site where Greater Bethlehem sits today, Frederick Douglass knew Emancipation was far from assured, according to historical records.

Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation, in part, as a threat against slaveholding states that refused to lay down their arms. Political forces amassed against Emancipation even in the North.

The first of January would be a dramatic day that told the character of America, Douglass wrote.

“It is a pivotal period in our national history — the great day which is to determine the destiny not only of the American Republic, but that of the American Continent,” he wrote in his abolitionist paper Douglass' Monthly.

“Far off in the after coming centuries, some Gibbon with truthful pen, will fix upon that date, as the beginning of a glorious rise, or of a shameful fall of the great American Republic. Unquestionably, for weal or for woe, the first of January is to be the most memorable day in American Annals…. But will that deed be done? Oh! That is the question: There is reason for both hope and fear.”

More:Due to repeated acts of vandalism, a Black history mural project has moved

More:Peace walk in Maplewood neighborhood reflects on 1964 Joseph Avenue uprising

At the AME Zion church at Spring and Favor streets — the first of three buildings to grace the site, though the original church’s timbers were used in subsequent construction — Douglass proclaimed his hope in a fiery speech Dec. 28, 1862.

“We stand today in the presence of a glorious prospect,” he said. “This sacred Sunday in all the likelihoods of the case, is the last which will witness the existence of legal slavery in all the Rebel slaveholding States of America.”

He warned that the struggle was not over.

“This is no time for the friends of freedom to fold their hands and consider their work at an end,” he proclaimed. “The price of Liberty is eternal vigilance.”

In Philadelphia and Boston and Washington, abolitionists held vigil for the signing on New Year’s Day.

“We were waiting and listening as for a bolt from the sky, which should rend the fetters of four million of slaves,” wrote Douglass, who joined abolitionists in Boston to wait for the fateful telegram that would announce freedom to enslaved people in rebel states.

However dramatic it would have been, freedom didn’t come at midnight, said Southern Methodist University historian Alexis McCrossen, at work on a book about the history of New Year’s Eve celebrations. Lincoln signed the document mid-afternoon on New Year’s Day.

Before he did so, she said, Lincoln spent a full three hours shaking hands, part of an old New Year’s Day tradition for U.S. presidents. In the meantime, Douglass fumed.

“Patience was well-nigh exhausted,” he wrote. “And suspense was becoming an agony.”

Finally the moment came. Fateful word came through the telegram wires. Slavery in Southern states had ended.

“The scene was wild and grand,” Douglass wrote. “Joy and gladness exhausted all forms of expression, from shouts of praise to sobs and tears.”

For many in the South, actual emancipation didn’t come for years. In the North and the Northern-occupied South, there were celebrations in the early days of 1863, wrote historian Mitch Kasun in “Festivals of Freedom,” a history of Emancipation celebrations. These featured “cannons firing, bells ringing, music, speeches, and spirited readings of the rather dry proclamation.”

The birth and continuance of the Watch Night tradition in America

If these joyous scenes took place on New Year’s Day and later, why is New Year’s Eve a date of remembrance for Emancipation?

It goes back to old Methodist practices and a bit of drama, said McCrossen. Watch meetings in America were a Methodist tradition going back to the 1740s, to greet the new year with hope and a renewal of faith.

For enslaved people, New Year's Eve watch meetings until 1862 took place amid tragedy: New Year’s Day was Heartbreak Day, Hiring Day, the day that families were broken up and enslaved people were rented out to different plantations. The Watch Night on 1862 was different.

“The Watch Night service that night would have had more intensity, at, say, a free Black church in D.C. or in Philadelphia, or even in the white churches that were strongholds of abolitionists,” McCrossen said.

In 1834 in the West Indies, there had indeed already been a Watch Night that counted down to the end of slavery — when emancipation was triggered Aug. 1.

“Those Watch Night services became very famous,” McCrossen said. “And they were written about over and over again, in American abolitionist newspapers or papers that were sympathetic to the abolition of slavery.”

And so the narrative of a Watch Night vigil to end slavery was already present. And so was the suspense of waiting for the signing.

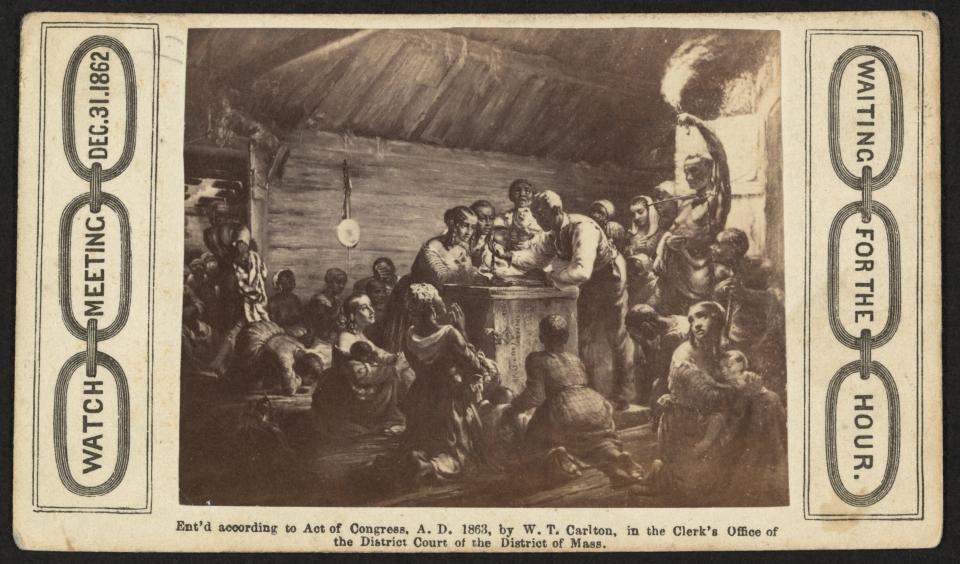

Already in 1863, William T. Carlton’s painting “Watch Meeting, Dec. 31, 1862, Waiting for the Hour” depicts a tense scene with a clock counting down to midnight, a Watch Night holding vigil for the mythical moment of liberation.

McCrossen suspects the secular traditions of New Year’s that began in the later 1800s, with their dramatic countdown to midnight — apples dropping and countdowns like the launch of a rocket ship — may extend from the drama of these much older Watch Nights

Broader observance of Watch Night services has waxed and waned over the intervening 160 years, McCrossen said, and so has the link between these services and Emancipation. It has remained a strong cultural tradition at Black churches in particular, she said.

At Bethlehem Greater Temple, Beverly Renford remembers the Watch Night services of her childhood.

“The pastor or designated ministers will preach many sermons until the clock struck,” she said. “And oftentimes people, the children that were not really following the religion, but their parents were members of the church, they would make sure that they stopped partying out in the street to be in church before that clock struck at 12 midnight.”

For Courtney Renford, Beverly's daughter, the meaning of Watch Night is as rich as it was 160 years before.

“It is still a community gathering for the Black population,” she said. “The only thing that has changed is that we're not waiting on the Emancipation Proclamation this time.”

Matthew Korfhage writes about culture, food and equity for the USA TODAY Network's Atlantic Region How We Live team. Follow him @matthewkorfhage on Twitter or email mkorfhage@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY NETWORK: Watch Night on New Year's Eve marks the wait for emancipation in U.S.