Yia Vang Made Some of the Best Food We Ate All Year. So Why Is He So Afraid of Failing?

With a name like Yia Vang, he was destined to work in kitchens. In the Hmong language, Yia means “iron skillet” or “wok.” The Hmong (pronounced with a silent h) are a stateless, nomadic people whose history reveals itself in their cuisine, which marries influences from Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, and Southern China. It is those spicy, smoky, mouth-walloping flavors that Chef Vang has worked tirelessly to bring to the national table.

Vang is the co-owner of Union Hmong Kitchen, a pop-up restaurant housed in a trailer outside Sociable Ciderwerks in Northeast Minneapolis. His seasonal offerings include char-grilled Hilltribe chicken with lemongrass sauce, blistered green beans with fried shallots, and other chili-lashed fare typical of a traditional Hmong household. (Our Test Kitchen says his recipes are some of the tastiest they’ve tried all year.)

Though Minnesota is home to the largest diaspora of Hmong people living outside Asia, no restaurant has been exclusively dedicated to Hmong cuisine. That’s about to change. In early February, Vang and his business partner, Dave Friedman, launched a Kickstarter campaign for Vinai, the Twin Cities’ first brick-and-mortar restaurant devoted to “the past, present, and future of Hmong cooking.” The ingredients will be sourced from Minnesota’s Hmong farmers and the restaurant will be filled with plants—a nod to Mama Vang’s green thumb. In the backyard will be a communal wood-fired grill—a fancier version of what Vang remembers tending alongside his dad at big family gatherings. The fundraiser, which closed on March 6, was backed by 899 patrons and exceeded its goal of $75,000 by more than $20,000.

In many ways, Vinai is a love letter to Vang’s parents—and the only way he knows how to thank them. Beyond the will-it-or-won’t-it-get-funded anxiety of putting all your eggs in a Kickstarter basket, and the can-we-or-can’t-we anxiety strangling the whole restaurant industry in this COVID-19 new world order, the idea of opening a “real restaurant” terrifies him. Even if the opening isn’t delayed, he’s worried it won’t survive its first year. Or that diners won’t get his food, or understand the history behind it. But mostly, he’s worried that he’ll disappoint the two people he most wants to impress: Mom and Dad.

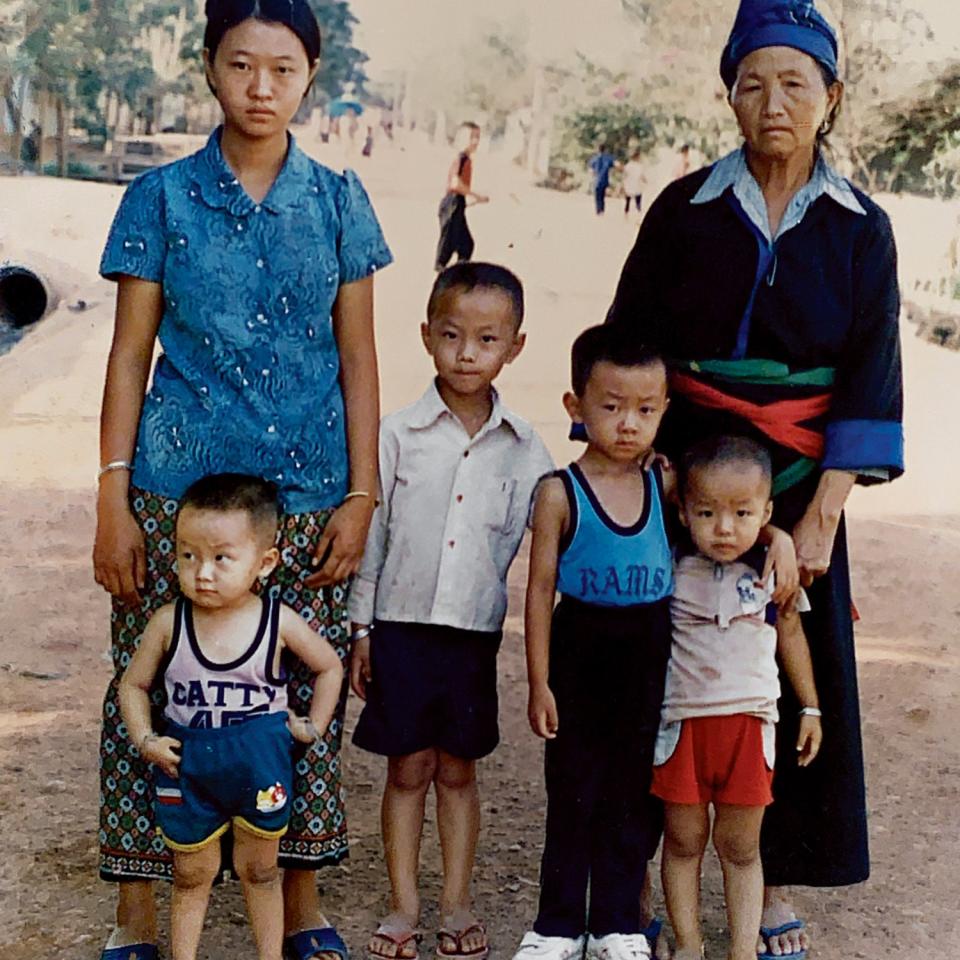

0520-Union-Hmong-chef-Yia-Vang-family.jpg

0520-Union-Hmong-Yia-Vang-family.jpg

“I get nervous because this is their legacy,” says Vang. “It’s their story, and if I eff it up, what does that say about how hard I tried?”

Vang named Vinai after Ban Vinai, the Thai refugee camp where he was born and where thousands of Hmong refugees passed through on their way to America. It’s also where his parents met almost 40 years ago.

Nhia Lor Vang, along with myriad other Hmong men born in Laos, was handed weapons by the CIA and trained in guerilla warfare during the Vietnam War. After the Fall of Saigon, American troops pulled out of northern Laos, leaving their Hmong allies in the crosshairs of a Viet Cong genocide. Thousands died; scores more disappeared. Vang’s father had no choice but to run; fellow soldiers and high-ranking officials followed. He spent six weeks hiding in the jungle before crossing the Mekong River on a rickety bamboo raft under the cover of night. Eventually he landed at Ban Vinai, where he met Vang’s mother, Pang Her. Both were widowers, having lost their spouses during the treacherous crossing—a not uncommon fate for Hmong refugees fleeing the war.

Vang was five when his family emigrated to America. Growing up in St. Paul, central Wisconsin, and Amish Country Pennsylvania, the war felt a million miles away. Vang’s childhood was filled with big family meals: the girls in the kitchen with their moms and aunties, steaming buns and making egg rolls; the boys in the backyard with their dads and uncles, tending the fire. Vang’s dad was the MacGyver of the house, always throwing tarps over sticks and jerryrigging a grill, no matter how lousy the weather.

Although Vang’s grandmother once told him about his family’s history, his parents did everything in their power to shield him and his six siblings from the hardships that brought them stateside. Vang later learned that his father could have stayed in Thailand, where he was feted as a war hero. Instead, he moved to a country where he didn’t speak the language and had to grunt it out at $7-an-hour factory jobs. But he did it for his children—to give them the kind of opportunities he never had.

Hearing these stories decades later, Vang feels a mix of pride and guilt. Pride because he, as a wizened adult, finally has an appreciation for the sacrifices his parents made. And guilt because he spends his days dreaming about food, and how to make it pretty and tasty. “My mom and dad didn’t have the luxury of ‘thinking creatively,’” says Vang. “All of their energy was [about] survival. When you realize that, it changes the way you do everything. It changes the way you care about people, the way you talk to people, the way you love people, and for me, it changes the way I cook.”

Vang began to weigh these issues while working in respected Twin Cities kitchens such as Spoon & Stable, Nighthawks Diner + Bar, and Borough. But it took a nasty accident for him to find his true calling.

Three years ago, Vang’s father slipped off a ladder and bashed his head on a railing. For two months, he lay in an ICU with a fractured skull and internal bleeding. “I was so mad, thinking to myself, This is not how a hero dies. Either he dies of old age, telling stories of his glories, or he dies on the battlefield fighting for what he believes in. But a hero does not die because he fell off a stupid ladder. And he doesn’t die in a hospital bed with nobody knowing who he is or all the things he’s done in his life.”

As his father recovered, Vang started asking more questions about what his parents had been through, why they chose America, and what it means to be Hmong in 2020. “[The accident] changed everything,” says Vang. “All I cared about was my mom and dad and telling their story.”

0520-Union-Hmong-chef-Yia-Vang.jpg

Vang sees Union Hmong Kitchen and Vinai as ways to do that. Vang has received gushing messages from Hmong people throughout the country, thanking him for raising the profile of their cuisine and their arduous journey as immigrants. He’s also had his share of detractors, with Hmong hardliners accusing him of bastardizing traditional recipes and making “fusion white people food.” Vang shrugs ’em off. “It’s an if-it-ain’-t-broke, don’t-fix-it mentality,” he explains. “The older generation likes eating a certain way, but braised pork neck with mustard greens won’t keep the lights on. I believe we can take those soulful dishes and translate them to the restaurant world.”

In addition to sharing his parents’ legacy, Vang wants to pay it forward—inviting Hmong chefs and other rising stars to hold pop-ups and residencies at Vinai after it opens. He hopes to eventually offer them seed money to help them pursue their own dream projects. “There are better ways to make money than to kill yourself opening a restaurant,” says Vang. “What drives my excitement for cooking is the stories we get to tell.”

Get the recipes:

Originally Appeared on Bon Appétit