York in American History: The death of the president

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Notes: The death of the 25th President William McKinley profoundly affected the nation. York was no exception. He was the third American president to be assassinated, following Abraham Lincoln in 1865 and James A. Garfield in 1881.

"In those hours when the service was being conducted over the bier of the martyred president in Canton, there was a bowing of heads throughout every part of the land..."

For a remarkable period of five minutes from 2:30 until 2:35 in the afternoon of September 19, 1901, the nation suspended all activity: "labor in shops, in stores, on farms, in mills ceased." During those five minutes, "from the Atlantic to the Pacific, not a wheel turned."

New York City abruptly grounded to a halt, as every church bell rang, "street cars, ferry boats, and railroad trains" stopped. Throughout the nation, the entire telegraph system was hushed, an action that required the cooperation of 100,000 operators. Portsmouth, New Hampshire "was in solemn silence during the day and in darkness at night." Businesses were closed. An unprecedented crowd attended a memorial service at the Music Hall.

Here in York, as in hundreds of other communities, that Thursday afternoon was just as memorable. "A Union service was held” at First Parish Church "at the hour when the funeral service... was being held at Canton, Ohio.” James T. Davidson, the director of the bank and an ardent Republican was among the speakers. Davidson had attended the party's nominating convention as a Maine delegate in 1896.

More: How York rallied to get electric bike for beloved town historian James Kences

In the two elections of 1896 and 1900, President William McKinley had received the majority vote from the town's electorate. With a total of 337 votes in the first election, he had far surpassed his rival who had obtained only 107 votes. Four years later, now with Theodore Roosevelt as his running mate, his candidacy held 268 votes, to William Jennings Bryan's 142 votes.

He was the third Republican president in the past forty years to have been slain by an assassin. The three deaths had been close to two decades apart, Abraham Lincoln in April 1865 and James Garfield in 1881. Both events were noted by York men in their diaries. "President Abraham Lincoln was shot through the head by an assassin in the theatre at Washington at 10 p.m.," Charles O. Clark wrote on April 14, 1865. And then, Joseph Bragdon wrote on July 2, 1881, "President Garfield was shot and dangerously wounded this morning in Washington..."

Garfield, mortally wounded, survived for over two months, and it is believed his death in September, was as much the result of the misguided actions of the attending physicians, as the bullet that had struck his body. Bragdon wrote, "President Garfield died last night at 10:35..." He had finally succumbed on the evening of September 19, twenty years to the day of the national moment of silence for McKinley.

"The news... came like a clap of thunder from the clear sky," was how the local newspaper, The Old York Transcript, depicted the reaction in town to the earliest report of the shooting of September 6, 1901. Apparently, there had also been a false announcement McKinley had been killed, "the excitement and horrified surprise that followed knew no bounds."

The president was visiting the Pan-American Exposition at Buffalo, New York. It was about four o'clock, near the close of the reception in the Temple of Music, an expansive, ornate, domed building. Leon Czolgosz, a professed anarchist, stepped from the crowd and fired two shots from a revolver, veiled by a handkerchief. One of the bullets had passed through McKinley's stomach but was not located. There were obvious fears of infection.

York in American History: The fate of Hugh Holman

Within minutes of the shooting, an Associated Press bulletin was transmitted to newsrooms throughout the nation, and this may account for the erroneous communication of his death received in York. The president remained alive for a week, and, at times, it seemed he might recuperate. A throng of journalists formed in proximity to the residence of John Milburn, where he had been taken for the much hoped for convalescence.

"Nearer my God to thee were the last words I heard my precious say..." the First Lady entered into her journal as the entry for Saturday, Sept. 14. McKinley died in the predawn hours, close to 2 a.m. His final words were from his favorite hymn, and the choir at the service held in York six days later chose that hymn, as did the church choirs in the thousands of memorials conducted on that strange, poignant afternoon of September 19.

Following a ceremony in Buffalo, the president's casket was brought to Washington D.C. in a train of only five cars draped in black. First at the East Room of the White House, and next to the Capitol, his body lay in state, to be viewed by an emotional crowd. Then, the train resumed its journey en route to Canton, Ohio, and arrived at the destination at noon on the morning of Sept. 18.

"The city was robed in black... crepe from public buildings and on private houses... Arches of mourning span the street..." This was how Canton appeared that day, and this was common to cities and towns throughout the nation. And true, it seems, for York as well.

"The front entrance of the Lancaster [in York Harbor] is artistically draped in mourning... In the center above the doorway is a picture of McKinley framed in black to either side of which is draped black and white bunting extending to the pillars on each side of the entrance..."

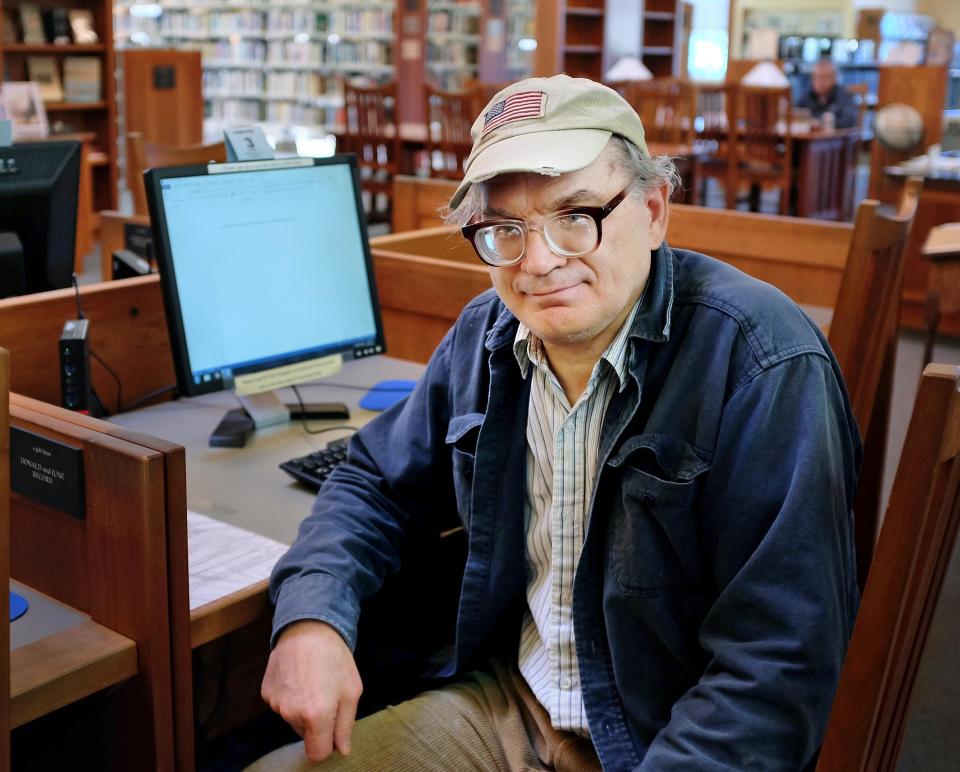

James Kences is the town historian for the town of York.

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald: York in American History: The death of the president