York in American History: The fate of Hugh Holman

Notes: Behind the Olde Gaol on Lindsay Road stands the Hugh Holman House built by him in 1727. In 1737 the Parish sold him the half-acre of ministerial land on which his house was standing. Early town records indicate that he was a fisherman and a weaver. Later, he was one of the "Snowshoe Men" of Capt. John Harmon's Company on the expedition to Louisburg in 1744. Historian James Kences follows his later adventures as he was taken prisoner after the defeat at Fort William Henry at the southern end of Lake George in what was to become New York State.

"Allow'd as drawback [from taxes] such as were in the Expedition..." This item in the Constable's Book from 1757-1758, maybe a reference to the men who took part in events at Fort William Henry.

Third in the list of eleven names, was Hugh Holman, believed to have died a prisoner in France, was taken into captivity during the aftermath of the surrender of the fort to an overwhelming force of French soldiers and their Indian allies.

What transpired in the early morning of August 10, 1757, known to many as the massacre, remains one of the most notorious events of the last of the four French and Indian wars. It happened as the garrison of British soldiers and provincial militia commenced a march towards Fort Edward after the surrender of William Henry. The provincials who were located at the rear, endured the heaviest losses.

It will never be known for certain but as many as 200 deaths have been estimated, and an even larger number of prisoners taken. While the majority were destined for Canada, to be sold into slavery, some indeed suffered Holman's fate on the other side of the Atlantic.

Fort William Henry was a small fort located at the southern end of Lake George, to the south of Lake Champlain in the New York western frontier. An aerial view reveals four bastions, the angular projections at each corner. From contemporary plans, and also successive phases of archaeological excavation, the fort and its interior buildings have been reconstructed.

The fort was established over two months in the autumn of 1755 upon the orders of William Johnson who had been placed in command of a planned siege of the enemy fortifications known to the British as Crown Point. As Fort William Henry, named in honor of two members of the royal family, the Dukes of Cumberland (William) and Gloucester (Henry), was being erected, the French had already begun work at Carillon, the site of the famous Ticonderoga, several miles to the north.

Two generations of York soldiers would become familiar with this region, with its connected lakes and rivers that crossed over the boundaries of New France and Canada, and the British provinces. At the far ends of the roughly north-south axis, was Albany on the Hudson River, and Montreal at the opposite end. During the Seven Years' War, and the American Revolution two decades later, multiple military campaigns would be directed at this strategic focal point.

York in American History: Whittier’s poem ‘Maude Muller’s Spring’

Only a year after local men participated in the defense of Fort William Henry, they would be present for the disastrous July 1758 battle at Ticonderoga. The British general on the field, James Abercromby, had ordered multiple frontal assaults upon the enemy's strong position. "Our forces fell exceeding fast," a witness recounted, "it was surprising that more of the regiments should be drawn up to the breast work for such slaughter." Eight townsmen were among the dead, and others would succumb from their wounds in the weeks that followed.

While the provincials were crucial to the war effort, they could expect little regard from the regular soldiers, and were often assigned strenuous or tedious duties; and even if they survived the battles, they might still fall victim to the epidemic diseases that swept through their encampments. The men arrived at their destination after having made the march of hundreds of miles from their homesteads.

York in American History: The fate of Thomas Venner

Hugh Holman first appeared in York during the 1720s, as a fisherman, and later a weaver. He resided in a house not far from the prison and the burial ground and was the father of six children. By the 1750s he was already a veteran of two earlier wars, in 1725, and at Louisbourg in 1745. He had already taken part in the campaign of 1756, the initial phase of the conflict that was to result in Britain's conquest of French Canada.

There had been rumors of a planned assault upon William Henry for months, when it occurred in early August 1757, the approach of the armada of Indian canoes and bateaux bearing cannon and soldiers must have made the garrison aware they were doomed, and it was just a matter of time. Lieutenant Colonel George Monro called upon 1000 soldiers fit for duty at the fort. The French under Montcalm had brought over 7000 men including 1600 Indian warriors from 33 tribal groups.

York in American History: A workhouse for the poor

The siege commenced in the early morning of August 6, when the first of the enemy batteries opened fire against the west side of the fort. Over the next four days the situation grew ever more desperate, and, as casualties increased, many of the losses were the result of injuries caused by exploding shells. The fort's total number of cannons was rapidly reduced, destroyed as they burst, one after another, in succession. The main provincial units were actually not at the fort, which could best accommodate only 400 men, but at a walled encampment a quarter mile to the southeast.

Aware that no reinforcements could be expected, and with the siege trenches and batteries advancing ever closer, on the morning of the 9th, the fort's defenders capitulated. Montcalm, who was impressed with the courage displayed, extended to the soldiers an honorable defeat. They were not made prisoners, but instead were required to pledge non-involvement in the war for the next 18 months and had to march under escort to Fort Edward.

The Indian warriors, who were forbidden to inflict harm upon the British, or to violently seize their clothing or possessions, failed to comprehend the French demands, and in a terrifying turn of events, attacked just as the march began. At first, they killed, but the taking of prisoners offered greater rewards. Obviously, it will never be known the exact circumstances of what happened to Hugh Holman, but this is the most likely explanation of the background.

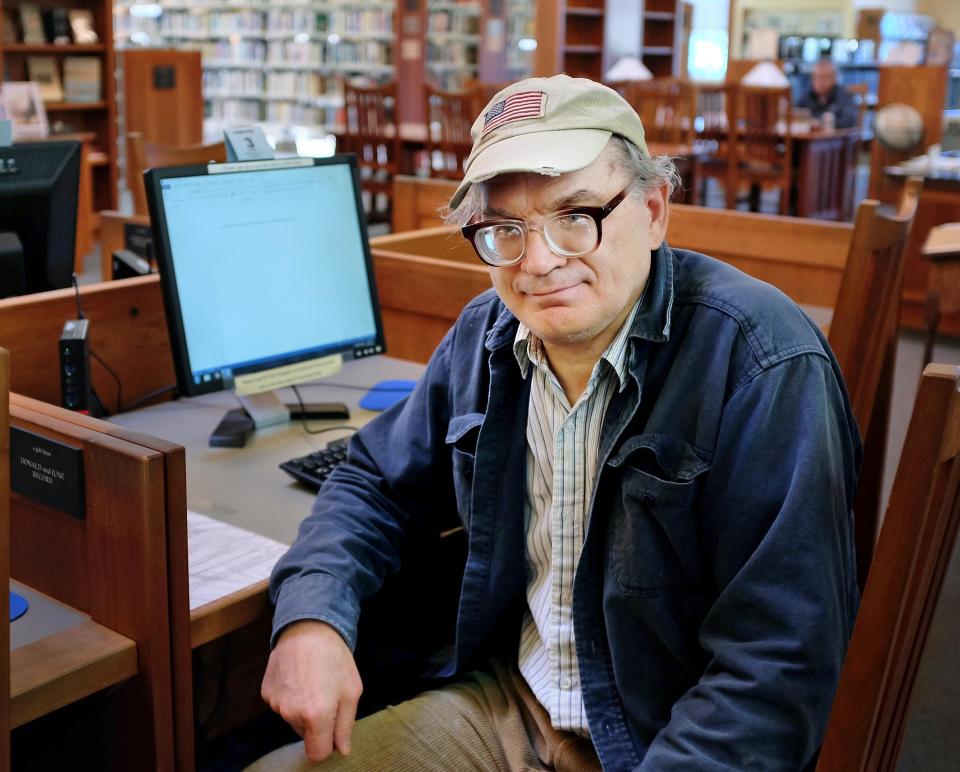

James Kences is the town historian for the town of York.

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald: York in American History: The fate of Hugh Holman